“Todo el mundo es literalista cuando se trata de la fotografía”, escribió Susan Sontag en uno de sus muchos intentos de desenmascarar las seducciones de la máquina de imágenes predominantes del siglo 20. Un invento (conjunto de inventos, si uno considera el cine y los engendros digitales de la reproducción mecánica, auto-replicándose rápidamente) que volvieron mayoritariamente obsoletas a las miméticas prácticas del siglo 18, el uso generalizado de la fotografía oculta por lo menos tanto como nos revela hoy. Doscientos años después del desarrollo del medio, pocas personas confían en su franqueza alguna vez convincente. Aún menos personas creen –en nuestra época de selfies [1] alteradas y fabricaciones políticas fabuladas– que su función “documental” está hecha de cualquier cosa más que de una irresuelta caja de sorpresas de tácitas verdades a medias.

De manera que ha llegado a pasar que aquel invento que el crítico de cine André Bazin una vez llamó “el evento más importante en la historia de las artes plásticas” se ha vuelto, en los primeros días del siglo 21, el instrumento de grabación más ubicuo y su tipo de tecnología más sospechosa. Aún más sorprendentemente: hoy solamente un puñado de artistas de importancia se dedican a entender la naturaleza histórica de la evolución de la fotografía. Entre ellos está la artista multimedia Mónica Bengoa. Una pionera ubicua en el campo de la realidad cotidiana y su tenue relación con la imagen contemporánea, la artista chilena ha seguido enfrentando procesos fotográficos cada vez más inestables a la obstinada solidez de las artes y oficios tradicionales. Sus resultados trazan las deficiencias del medio. Representados bajo la apariencia de trabajosas re-interpretaciones, sus llamativas versiones de reproducciones mecánicas logradas por medios caseros literalmente materializan (¿o re-materializan?) la conexión cada vez más efímera de la fotografía con lo real.

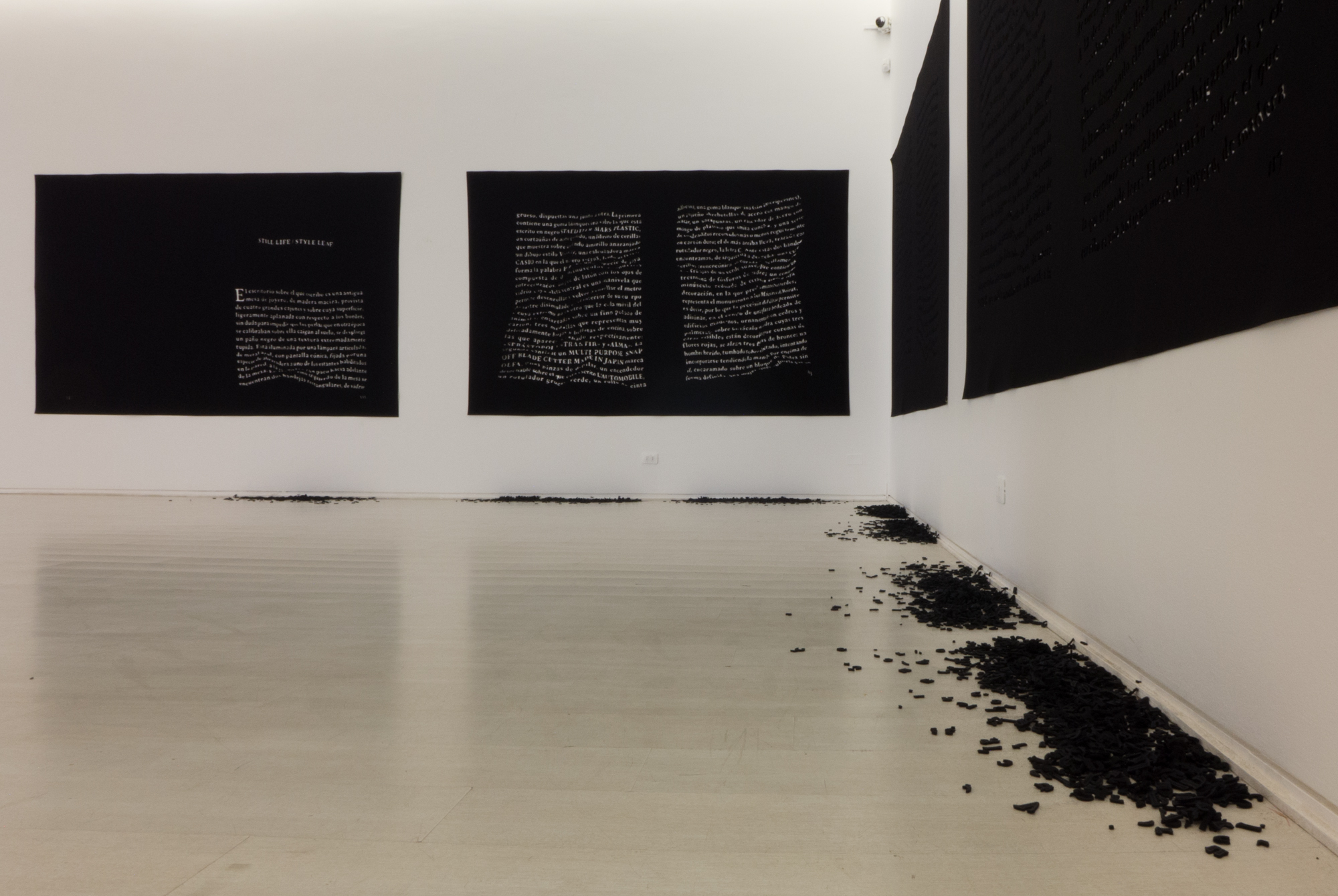

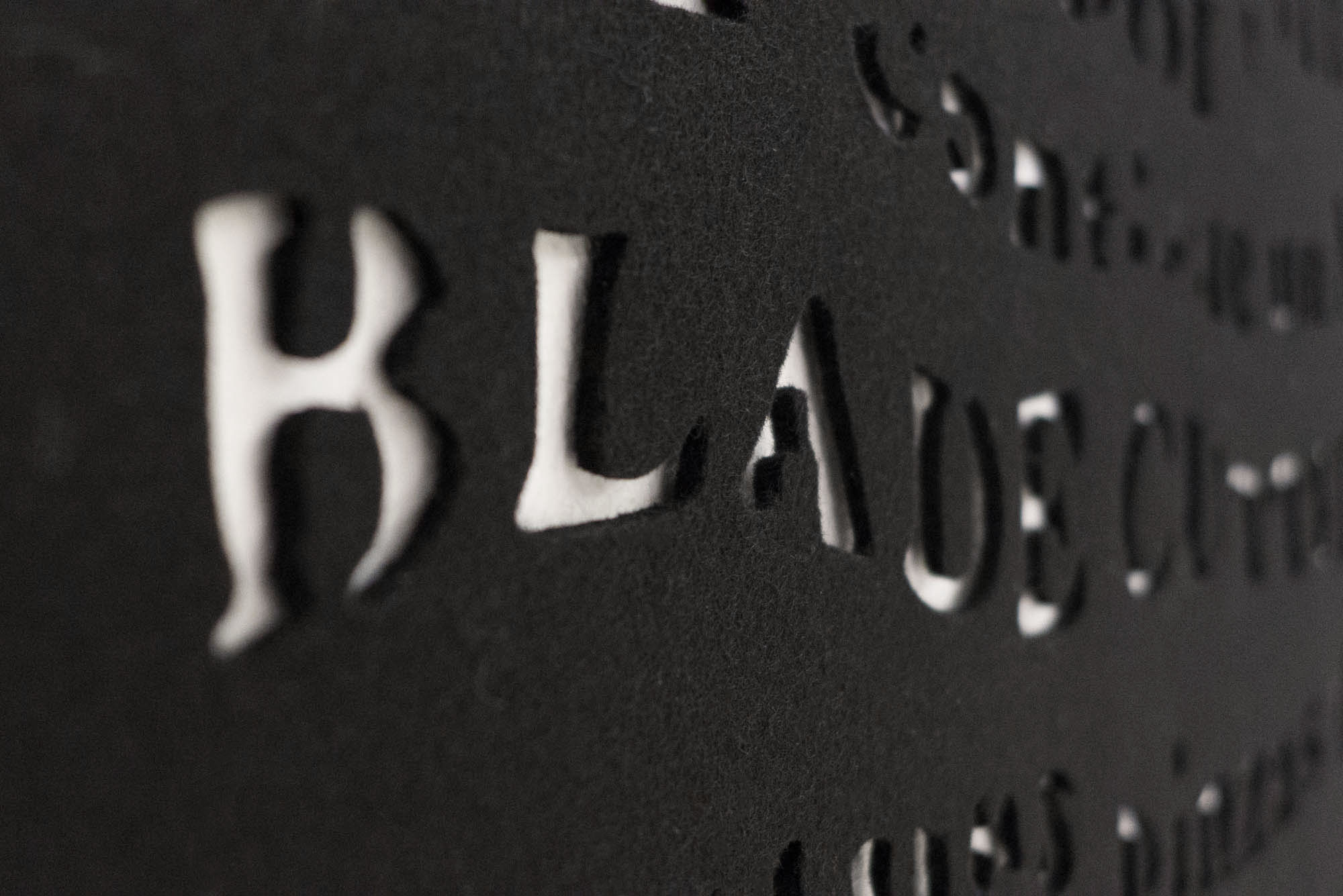

Una artista que ha pasado décadas traduciendo fotografías de goce doméstico hacia prácticas manuales como el dibujo, pintura, bordado, estarcido, corte de telas, y utilización de cuadrículas, Bengoa ha recientemente migrado hacia el uso de textos encontrados para volver a la fotografía y sus soportes técnicos más, en vez de menos, visibles. Sus primeros experimentos en esta nueva modalidad incorporaron el uso de enciclopedias de historia natural en alemán: libros sobre flora y fauna cuidadosamente fotografiados, sus imágenes y descripciones, se volvieron, en sus manos, tapices a gran escala capaces de clasificar, tanto fenómenos naturales como las distorsiones altamente no-naturales de la cámara fotográfica (considerar por ejemplo, la idea de una profundidad de campo limitada). Desde ahí, Bengoa prosiguió hacia su más nuevo experimento: ejecutar una instalación a tamaño de una habitación –basada en fotografías usando nada más que tela y texto. Tomando prestado del canon post-moderno –concretamente, Still Life / Style Leaf de Georges Perec, el cual contiene un desglose recursivo de múltiples artículos en el escritorio de un escritor– Bengoa transformó este listicle [2] primero en una plantilla, y luego en un ambiente de una imagen en cuatro partes recortada en negativo de fieltro de color carbón de distintos largos.

Una obra que les da forma sólida a ideas que de otra manera seguirían siendo altamente abstractas –la artista se aseguró de desafiar al lente de la cámara arrugando hojas de papel individuales con el texto de Perec antes de representar sus imperfecciones de manera equivoca– la instalación de cuatro paños de Bengoa constituye una traducción física de algunas de las funciones más dubitativas de la fotografía. Donde la cámara registra una falta de foco, los retorcidos contornos del texto de Perec adquieren un relieve especialmente significativo. En donde la información visual escasea –digamos, por ejemplo, en áreas de una reproducción en la que ocurre el alto-contraste– Bengoa suministra evidencia de esa ausencia en las letras de fieltro apiladas en el piso. Pocas obras contemporáneas problematizan temas complejos con una inmediatez tan esmerada.

Tomando una página de Sontag, Bengoa hace físico lo que permanece mayoritariamente oculto tanto dentro como fuera de la cámara (para la segunda, considerar momentáneamente la vasta red de imágenes del mundo). De hecho, todos son literalistas cuando se trata de fotografía, pero pocos más que esta artista chilena. Una figura que sabe que verdades básicas están en juego en los resbalones multiplicados de la fotografía –especialmente aquellos que tienen que ver con cómo se nos enseña a mirar– ella nos recuerda de manera consistente justamente cuán lejos tienen que llegar las imágenes modernas antes de que, de hecho, se re-involucren honestamente con lo real.

[1] Neologísmo del inglés que refiere a un autorretrato/foto de perfil, cámara en mano, para ser subido a alguna red social en internet. N. del T.

[2] En inglés, combinación de las palabras list (lista) y article (artículo) para referirse a un texto corto basado en una lista, como por ejemplo las “nueve cosas que hay que saber respecto a los listicles”. N. del T.

*traducido del inglés por José Miguel Trujillo

Christian Viveros-Fauné

Escritor, curador y crítico de Arte

Texto realizado en ocasión de la exhibición de la obra Still life / Style leaf en ARCO, Madrid, España. 2014.

The Literalist: Lessons in Looking, Courtesy of Mónica Bengoa’s Handmade Photography

“Everyone is a literalist when it comes to photography,” Susan Sontag wrote in one of her many attempts to unmask the seductions of the 20th century’s predominant image machine. An invention (or set of inventions, if one considers cinema and the rapidly replicating digital spawn of mechanical reproduction) that rendered the mimetic operations of 18th century art largely obsolete, the widespread use of photography hides at least as much as it reveals today. Two hundred years after the development of the medium, few folks trust its once compelling directness. Fewer still believe –in our age of altered selfies and whole cloth political fabrications– its “documentary” function to be made up of anything more than an unsettled grab bag of tacit half-truths.

So it has come to pass that the invention film critic André Bazin once called “the most important event in the history of the plastic arts” has, in the early days of the 21st century, turned into both the world’s most ubiquitous recording device and its most suspicious kind of technology. More surprising still: just a handful of important artists devote themselves presently to understanding the epochal nature of photography’s evolution. Among them is the multi-media creator Mónica Bengoa. A far-flung pioneer in the field of quotidian reality and its tenuous relationship to the contemporary image, the Chilean artist has continued to pit increasingly unstable photographic processes against the stubborn solidity of traditional arts and crafts. Her results map out the shortfalls of the medium. Rendered in the guise of labor-intensive reinterpretations, her eye-catching versions of mechanical reproductions achieved via homespun media literally materialize (or is that re-materialize?) photography’s increasingly ephemeral connection to the real.

An artist who has spent decades translating photographs of domestic bliss into intensely manual practices such as drawing, painting, needlepoint, stenciling, fabric cutting, and pattern tiling, Bengoa has recently migrated to the use of found text to make photography and its technical supports more, rather than less, visible. Her first experiments in this new modality featured the use of German-language encyclopedias of natural history: carefully photographed books of fauna and flora, their pictures and descriptions became, in her hands, large-scale tapestries capable of classifying both natural phenomena and the highly unnatural distortions of the photographic camera (consider for example, the idea of a shallow depth of field). From there, Bengoa moved onto her newest experiment: making a room-sized photo-based installation using nothing but cloth and text. Borrowing from the postmodern canon –namely, Georges Perec’s Still Life / Style Leaf, which features a recursive itemization of multiple items on a writer’s desk– Bengoa transformed this literary listicle first into a stencil, and then into a four part image environment sliced out negatively from separate lengths of charcoal-colored felt.

A work that gives solid form to ideas that would otherwise remain highly abstract –the artist made sure to challenge the camera’s lens by crumpling individual sheets of paper containing Perec’s story before equivocally picturing their imperfections– Bengoa’s four-sided installation constitutes a physical translation of some of photography’s most dubitative functions. Where the camera records a lack of focus, the twisted contours of Perec’s text acquire especially meaningful relief. Where visual information is scarce –say, for example, in areas of a reproduction where high contrast occurs– Bengoa provides evidence of that absence in the shape of felt letters piled up on the floor. Few artworks today problematize complex themes with such thoughtful immediacy.

Taking a page from Sontag, Bengoa makes physical that which remains largely unseen both inside and outside the camera (for the latter, consider momentarily the world’s vast image web). Indeed, everyone is a literalist when it comes to photography, but few more so than this Chilean artist. A figure who knows that basic truths are at stake in photography’s multiplying slippages –specifically those having to do with how we are taught to see– she consistently reminds us of just how far modern images have to go before they actually, honestly reengage with the real.

Essay written in the context of the exhibition of the installation Still life / Style leaf in ARCO, Madrid, Spain. 2014.