Sobre cuentos

Un famoso cuento de Julio Cortázar narra cómo Alina Reyes –bella, joven, elegante– se cruza en un puente, en una ciudad extranjera y desconocida, con una mendiga harapienta, de inquietante mirada. Alina Reyes pasa, y luego mira a la mendiga una vez más; pero lo que ve es a Alina Reyes alejándose. Se mira, entonces, mira su cuerpo. Los harapos le cuelgan, y las manos que se muestra son viejas, sucias, heridas. Es un cuento que refleja muy bien las ansiedades de un mundo cuya clave es más bien psicoanalítica. En ella, el otro yo, el oculto, el terrible, el negado, el reprimido, el contrario, pasa a «tomarse» el yo. El anagrama del nombre: «Es la reina y…»[i]

Se siente un poco brutal, un poco elemental, la estructura del cuento de Cortázar al contrastarse con el que Mónica Bengoa presenta en este mismo catálogo. El contraste interesa sobremanera, me parece, por cuanto es revelador de un cambio de época, un cambio en la percepción del yo o del sujeto. También trata de un doble, un «otro yo»: pero no es el psicoanalítico del cuento anterior, que, visto desde otro lugar, revela una raigambre más bien romántica –prolongada en las fantasías del doppelgänger– y nada tiene que ver con una reina y una mendiga, con el juego de contrastes de lo extremo.

La del cuento de Bengoa es una imagen prácticamente idéntica a «ella», la protagonista; pero, como en un verso de Verlaine, «ni es totalmente la misma ni es totalmente otra».[ii] En este cuento lo que interesa no es una dramática sustitución, como en Cortázar, ni un dramático enfrentamiento, como con el doppelgänger. Es la mínima diferencia entre uno y otro yo, el pequeño espacio intermedio, una especie de oscilación callada entre los dos: ser y no ser la misma, o ser la misma más un mínimo enigma, una mirada fugaz, un ser y no ser, mínimamente también, «un otro», para rendir los debidos respetos a la frase de Rimbaud. Que no se apodera de «ella»: que se queda a una precisa distancia, la permitida por el pudor; que la reencuentra a intervalos fijos, «sentada frente a ella, sonriéndole» «en el suave movimiento de la balsa…»

Veo en ese breve cuento de Bengoa algo así como una cifra de su sutil poética. Quisiera desentrañar algo de esa poética en este texto sobre su obra visual más reciente.

Sobre píxeles

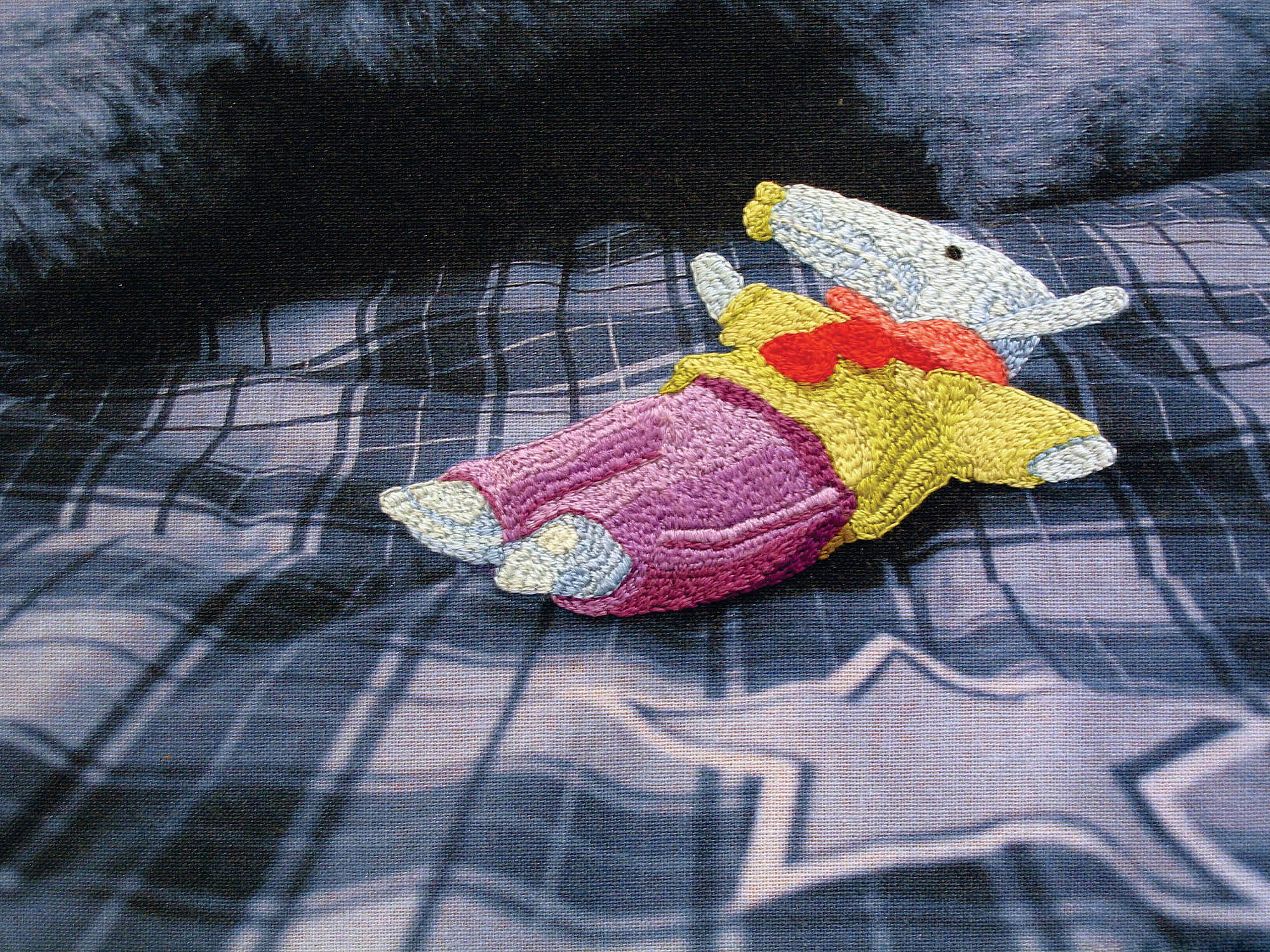

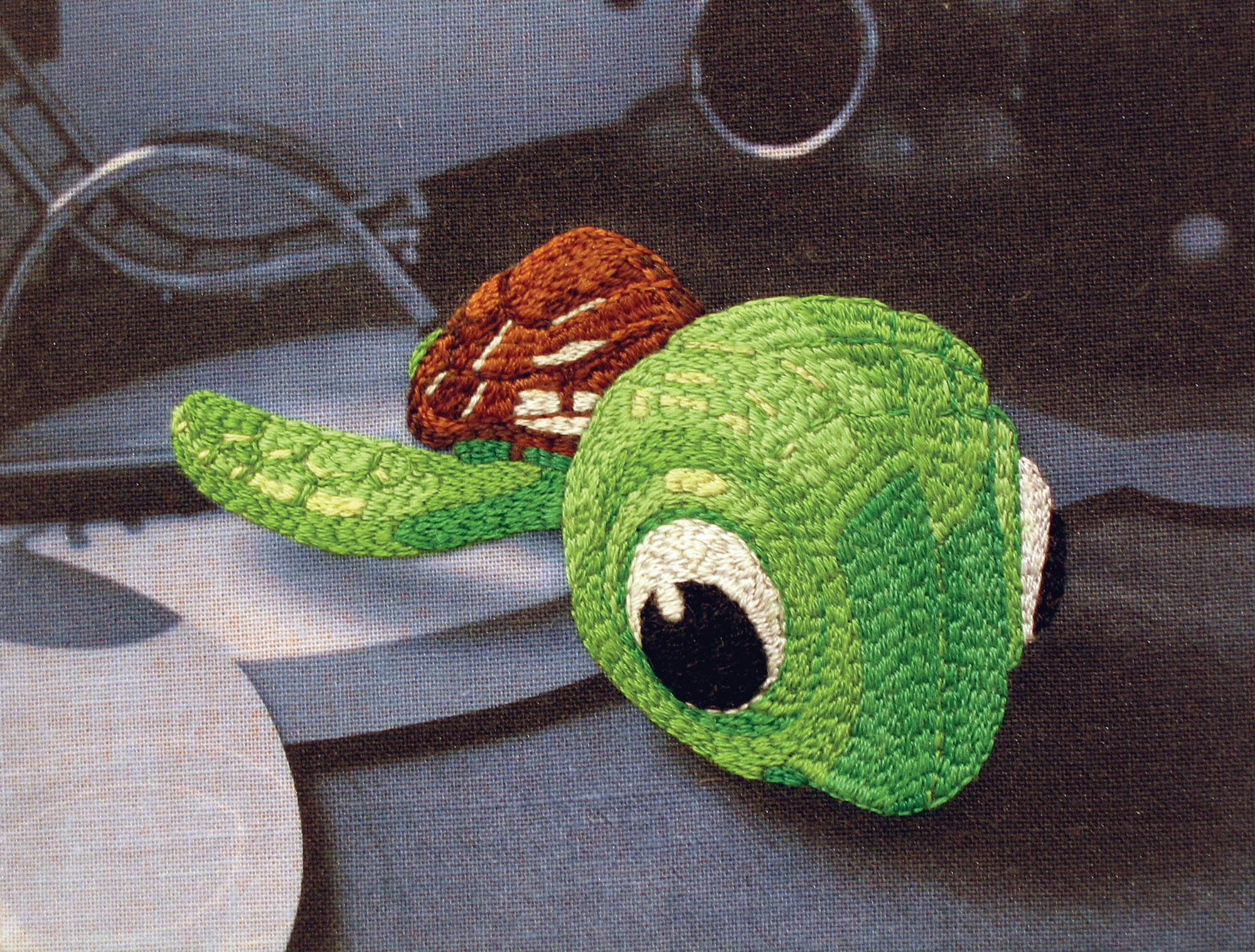

En el gran mural de la segunda sala, en Galería Gabriela Mistral, Mónica Bengoa presenta un mural que cubre totalmente el más grande de los muros. Visto de lejos, revela su procedencia fotográfica; más todavía, los colores de una fotografía digitalizada, vistos en la pantalla de un computador. Al acercarse, se aprecia que está hecho por innumerables cuadrículos coloreados a mano, reconocibles como servilletas de papel. Estos reproducen los colores de la pantalla lo más exactamente posible, sirviéndose de una «paleta de color» –a su vez, colores ya industrialmente determinados– que se aplican según el diseño a cada una de las servilletas («servilleta-pixel», dice la presentación escrita del proyecto). En la primera sala, cada uno de los pequeños bordados a mano sobre objetos-juguetes fotografiados a escala natural son llamados, por extensión, «puntada-pixel». Los objetos son de producción mecánica, como la imagen fotográfica; las puntadas, hechas a mano, como las servilletas.

Cabe recordar la reciente etimología de «pixel». «Pix» es una abreviatura familiar (una de las muchas del inglés de los Estados Unidos) usada desde hace muchos años para referirse a una película cinematográfica o a una fotografía, ambas llamadas «pictures». «El», otra abreviatura, es de «element».[iii] Las servilletas coloreadas, entonces, son los elementos de los que se sirve la artista para reconstruir una imagen mecánica; también lo son los bordados.

La sola enumeración de las técnicas utilizada por Mónica Bengoa encamina el análisis hacia ciertas paradojas. Una imagen de una escena doméstica reconocible, enorme, ampliada mucho más allá de la escala «natural», pero cuya superficie está compuesta por innumerables elementos pequeños, ninguno de ellos una imagen en sí mismo, apenas un elemento de una imagen. La imagen enorme es fotográfica, es decir, reproducible infinitas veces, carente de un «original» a que referirse, y por lo tanto carente del aura de lo único, y carente de cualquier huella de la mano del artista. Sin embargo, sus elementos son pequeños, artesanales; las servilletas de papel llevan, incluso, las marcas del género (de la tela texturada) sobre la cual estuvieron mientras eran coloreadas a mano. Presencia y ausencia de lo grande y de lo pequeño; presencia y ausencia de lo mecánico; presencia y ausencia de lo manual. Paradojas que la obra no intenta resolver, sino poner en escena.

Sobre lo indecidible [iv]

Esta puesta en escena de Bengoa –tan personal como es– corresponde a un momento más general del arte, que se aleja de las oposiciones binarias: la reproducción mecánica vs. la manualidad, por ejemplo. Tal vez tenga más que ver con un pensamiento contemporáneo dado a jugar con la paradoja, sin pretender resolver la oposición.[v] (A eso me refería con «poner en escena» ambos polos, jugar con su posible relación, rehusar una oposición que hace inclinarse por uno y oblitera el otro.)

La obra crea una escena para lo indecidible, y su fuerza está entonces en desconstruir oposiciones, suspender indefinidamente su resolución y preferir la extrañeza –el efecto de extrañamiento– a cualquier efecto de verdad.[vi] Crear la extrañeza es su peculiar manera de hacer ver cosas que –por economía, por costumbre– no vemos ya, y que curiosamente son los «soportes receptores de esas acciones reguladas que marcan nuestros días», según dice la artista: los objetos de uso cotidiano. «La atención que he puesto en ciertos objetos de uso cotidiano se fundamenta principalmente en lo irrelevante de su presencia en nuestro accionar diario, al menos en términos conscientes», agrega.[vii]

En términos conscientes… La poesía, dijo alguna vez Armando Uribe, es una expresión de lo inconsciente. Tal vez no sea tan así; pero en arte y poesía la zona de trabajo es la del borde de lo inconsciente: una escena a la que nos aproximamos con el oscilante movimiento propio de lo indecidible y lo paradojal.

«Al son de un suave y blando movimiento» [viii]

El cuento de Bengoa, al terminar, habla de un movimiento suave. Al referirse a la producción y el montaje del mural, señala que las servilletas estarán sostenidas en el muro sólo desde su borde superior, de manera «que es posible que se muevan si se produce alguna corriente de aire.»

El efecto de la gran escala del mural está, entonces, hecho de pequeños efectos que incorporan en la enorme imagen un pequeño temblor suave, ocasional. Apenas se percibe ya ha terminado: como un escalofrío súbito y fugaz, el movimiento suave del papel, su mínimo recuerdo de unas alas pequeñísimas. Una gran imagen fija, entonces, que incorpora su propia fragmentación y su propio movimiento. Otro ejemplo del poner en escena lo paradojal, de dejar al espectador viendo no sólo una superficie, sino también, en ella, el suspenso productivo de lo indecidible.

La gran imagen «pixelada», que incorpora su propio movimiento, registra algo aparentemente no memorable, un dormitorio de niño. («Lo memorable» –dice un personaje de una película de Jarmusch, Mystery Train– «siempre será recordado. Lo que hay que registrar es lo insignificante.»)

Lo cotidiano y sus sutiles diferencias

Esta obra, enero, 7:25, es parte de una «exploración sobre la puesta en escena de la vida cotidiana familiar», dice la artista. Como parte de esa exploración, sus trabajos anteriores eran instalaciones murales de muchas fotografías de sus hijos pequeños («una extensión de mi propia piel») durmiendo en noches distintas (En vigilia), o lavándose los dientes en días sucesivos (En vigilia IV). Fotografías aparentemente iguales o muy parecidas, las diferencias entre ellas eran a veces muy sutiles, o, para usar el término propuesto por Duchamp, inframinces –infrafinas, se traduce, o infraleves, o infrathin, o, en italiano, ultrassotile… Se refiere a la diferencia casi imperceptible entre dos objetos aparentemente idénticos. «En el tiempo» escribió Duchamp, «un mismo objeto no es el mismo tras un intervalo de un segundo– «¿qué relación hay con el principio de identidad?»[ix] Recuerdo aquí el relato de Bengoa que comenté al iniciar este texto: la diferencia mínima entre ella, y «ella, ella misma, sentada, mirándola», es infrafina, en ese mismo sentido. «Pienso», escribía también Duchamp, más bien enigmáticamente, «que a través de lo infrafino es posible ir de la segunda a la tercera dimensión.»

Este traslado a otra dimensión (y el consiguiente extrañamiento) es lo que sucede también con las diferencias sutiles entre las obras indicadas, y también con Sobrevigilancia (2001), que –por otros medios, utilizando esta vez 9160 flores de cardo teñidas– crea un enorme mural con la figura del lavatorio que aparecía en En vigilia IV. La vida a la que se alude aquí es la de las prácticas diarias –la de la extrañeza cotidiana que la superficie de la imagen recubre, que se revela en sus temblores y en sus fragmentaciones. La extrañeza de «una forma específica de operaciones –de maneras de hacer– una espacialidad otra (…), un movimiento opaco y ciego» que escapa a «las totalizaciones imaginarias del ojo», dice Michel de Certeau, en su Invención de lo cotidiano.[x] Son sólo estas totalizaciones del ojo las que dan la ilusión de poder «mirar»: «ser sólo este punto que mira es la ficción del saber», y del poder omnividente. Lo cotidiano, es su roce, es un permanente desmentido a tal ficción del saber.

Lo que se pone en escena en enero, 7:25 juega con este simulacro «teórico» (es decir, visual), asimilable a la mirada de un mapa. La gran imagen –que podría tomarse como un mapa– al estar fragmentada, disgregada, potencialmente temblorosa, y acompañada en la sala contigua por los pequeños bordados (puntada-pixel), se transforma de mapa en recorrido: no basta con verla, hay que recorrerla como un caminante. La gran imagen bañada en luz técnica, hiperreal –pero hecha de fragmentos y diferencias mínimas– apunta a otra cosa que su luz, fascinante como la de una pantalla. Se las arregla para hacer pensar también en lo que no es nunca tan claro, en los entrelazamientos y texturas de las prácticas diarias, ubicadas bajo los umbrales de la visibilidad.

La vigilia y la sobrevigilancia –agotadoras– apuntan a un «no perder de vista por donde se transita», en palabras de la artista; a no perder de vista la extrañeza densa de las prácticas cotidianas; a un abocarse a estudiar la «texturología» (la palabra es de de Certeau), de los saberes que inventan lo cotidiano. Es un saber de «las condiciones de dormir, de comer, de cocinar, de vestirse, de lavarse los dientes, etc.», dice la artista. La atención está puesta en sugerir lo que de Certeau llama «la invención de lo cotidiano», la creatividad «dispersa, táctica y bricoleuse» que de mil maneras furtivas va conformando la vida diaria –y cuyos trayectos no se incluyen en mapa alguno, y de las que se tiene «un conocimiento tan ciego como el del cuerpo-a-cuerpo amoroso.» La obra presenta una imagen hiperreal que contiene, evoca, suscita algo irrepresentable: su propia ceguera, tal vez, lo que queda fuera de su luz; por ejemplo, esta imagen hecha de manualidades que la pantalla oblitera…

Lo cotidiano: la verdad como proyecto y como resistencia

La sutil poética de estos trabajos de Mónica Bengoa… Tal vez el camino recorrido en este texto haya acercado un poco más la posibilidad de aventurar algunas hipótesis, con miras a una futura conversación, a un futuro espacio de encuentro.

Está el tema de la verdad. «Para saber si está Bien o está Mal tenemos una regla muy sencilla: la composición debe ser verdad. Debemos describir lo que es, lo que vemos, lo que oímos, lo que hacemos.»[xi] Cuaderno en mano, la artista produce como los gemelos de El gran cuaderno. Lo cotidiano: lo que es, lo que vemos, lo que oímos, lo que hacemos, nuestras prácticas. ¿En qué mundo? ¿En el del simulacro «hiperreal» de las pantallas de TV y de computadoras, de las imágenes digitalizadas, en que naufraga –se ha dicho– la realidad, en su alucinante parecido consigo misma?[xii] ¿Cuál es la vista, cuál el oído, cuáles los otros sentidos que permiten acceder hoy a la verdad?

Si no se puede propiamente contestar preguntas semejantes, es porque son retóricas: implican su propia respuesta – y su respuesta es la sospecha, la duda ante la posibilidad de describir lo que es, lo que vemos, lo que oímos, lo que hacemos. El trabajo de Bengoa puede verse como una actividad continua encaminada a aguzar los sentidos (que tal vez sean otros, complementarios de los proverbiales cinco): se trata de poder ver no sólo la imagen totalizadora y deslumbrante. Se trata de trabajar de mil modos esa imagen, ese falso cotidiano ofrecido, para cuestionarlo desde adentro, desde las diferencias infrafinas que lo arman y a las que sirve de encubrimiento. El acceso a lo que realmente vemos, a lo que realmente oímos, a lo que realmente hacemos no es un dato, al contrario: es un proyecto.

Se trabaja ese proyecto en lo más íntimo: con la propia piel. (Sabemos ya que los hijos son para ella «mi propia piel», también). Con las manos. Con el borde del inconsciente. Con los bordes de la experiencia, si se puede hablar de experiencia. Con la dificultad de acercarse sin brutalidad, a prudente distancia, al propio sujeto, un sujeto siempre a la vez viviéndose y mirándose, existiéndose y difiriéndose. Se trabaja contra el empobrecimiento –de las experiencias sensoriales y de relación con el mundo– que se produce en un mundo dominado y absorbido por la técnica. Lo cotidiano es el terreno de ese trabajo de «microrresistencia»[xiii], donde se va produciendo una mirada –a lo familiar, lo femenino, lo materno– ajena y subversiva en relación a los clichés de uso público, profundamente meditativa, atenta a las operaciones sutiles y aparentemente anónimas que tienen que ver con las «estructuras de contención» que la artista ve en los gestos reiterativos de la vida diaria. El oficio manual es clave y huella de esa microrresistencia, y de un saber de distintos tiempos y movimientos.

Enero, 7:25 transforma la Galería Gabriela Mistral en el «taller de turno», donde el proyecto se trabaja no sólo físicamente, sino también en relación a un particular contexto de recepción y exhibición. Aquí (en un «intersticio» de esta ciudad) se ponen en escena temas y procedimientos propios del proyecto, pero también de las preocupaciones más contemporáneas del arte mundial. Aquí se está proponiendo al espectador sumarse al movimiento de estas obras, que es exploratorio: de lo real en los tiempos de lo hiperreal, de lo cotidiano en cuanto investigación y proyecto, de lo sutil y fino de una «necesaria inestabilidad», de una suspensión y un diferimiento que nos mantiene «suficientemente alertas como para no tropezar y caer»… Son palabras de la artista.

Adriana Valdés. Octubre 2004.

[i] «Lejana» en Bestiario, libro publicado en 1951.

[ii] Poèmes saturniens: «Ni tout a fait la même ni tout a fait une autre».

[iii] Nicholas Mirzoeff, An Introduction to Visual Culture, New York and London, Routledge, 1999, p.30.

[iv] A modo de pequeño homenaje a Jacques Derrida, cuya muerte lamentamos al redactar este texto.

[v] Mis agradecimientos a Ticio Escobar por una conferencia luminosa que dio este año en Sao Paulo sobre este tema, en el marco de un coloquio llamado «Zonas de resistencia», durante la 26a. Bienal.

[vi] Al decir «efecto de extrañamiento» cito el famoso texto de Victor Chlovski, «L’art comme procédé´», en Théorie de la littérature, Textes des Formalistes russes réunis, presentés et traduits par Tzvetan Todorov, Paris, Seuil, pp.76-97.

[vii] Mónica Bengoa, citada en Transferencia y densidad, Tercer período, 1973-2000, Santiago de Chile, Museo de Bellas Artes, 2000, p. 97.

[viii] Del poema «Gladiolos juntos al mar», del poeta chileno Óscar Hahn.

[ix] Marcel Duchamp, Notes, translated by Paul Matisse, Boston, G.K. Hall&Co., 1983, cfr. pp.1-46.

[x] L’invention du quotidien, capítulo 7, Marches dans la ville: «Voyeurs ou marcheurs». Lo que sigue, evidentemente, le debe mucho.

[xi] En Mónica Bengoa, cuaderno en mano. Es una cita de la novela de Agota Kristof El gran cuaderno.

[xii] Cfr. Jean Baudrillard, citado en Art in Theory, 1900-1990, Edited by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, Blackwell, 1992, p.1050.

[xiii] Nicolas Bourriaud, «Les utopies de micro-proximités», Spirale No.182, enero-febrero 2002.

Adriana Valdés

Ensayista y crítica

En catálogo de exposición enero, 7:25, p.16-30. Santiago, Chile. 2004

(I would like to write a text as fine as your work)

About stories

A famous story by Julio Cortázar narrates how Alina Reyes –beautiful, young, elegant– runs into a ragged beggar with an unsettling look on a bridge in a foreign and unknown city. Alina Reyes walks on and then looks at the beggar once more; but what she sees is Alina Reyes walking away. She then looks at herself, her body. Rags are hanging from her and her old, dirty and wounded hands. The story is a very good reflection of anxiety in a world as seen from a rather psychoanalytic perspective. In it, the other, hidden, terrible, repressed, contrary self goes on to “take over” the “I”. Alina Reyes’ name, in Spanish, is an anagram for “She is the queen and…”[I]

Cortázar’s story structure feels somewhat brutal, elemental, when compared to the one Mónica Bengoa includes in this same catalogue. The contrast seems interesting to me because it reveals how times, self-perception and ideas about the subjective have changed. Bengoa also deals with a double, an “alter ego”: but hers is not the psychoanalytical one from the Cortázar story, which, from a different viewpoint, appears rather romantic –related to doppelgänger fantasies. Bengoa’s bears no relation to extreme contrasts such as that between a queen and a beggar.

Bengoa’s story shows an other practically identical to “her”, the protagonist; but like Verlaine puts it, “neither totally the same nor totally something else”.[ii] The point of this story, unlike that of Cortázar, is neither a dramatic substitution nor a dramatic conflict, as with the doppelgänger. The minimal difference between one me and the other, the small intermediate space, a kind of quiet oscillation between the two: to be and not to be the same, or being the same with a minimal enigma, a quick glance; to be and to be, minimally also, “an other”, in Rimbaud’s famous phrase. An other that does not take possession of “her”: that stays at a precise distance, allowed by respect; and that reappears to her at fixed intervals, “sitting in front of her, smiling” “in the raft’s gentle movement…”

I see something like a cipher of her own poetics in Bengoa’s brief story. In this text about her more recent visual work, I would like to deal with some aspects of this.

On pixels

In the second room at Gabriela Mistral Gallery, Mónica Bengoa presents a mural which covers the largest wall in its totality. Seen from afar it reveals not only its photographic origin, but also that its colors are those of a digitalized photograph as seen on a computer screen. When coming closer one can see that it is made of countless hand-colored squares recognizable as paper napkins. These reproduce the computer screen colors as exactly as possible, using a “color chart”, a set of already industrially determined colors applied on each of the napkins according to the work’s design. (The project’s written presentation mentions “pixel-napkins”). In the first room each of the small hand-made embroideries are also composed of “pixel-stitches” on toys photographed in their actual size. The toys, like the photographs, are the products of of mechanical reproduction, while the stitches, as well as the colored napkins, are handmade.

It may be useful to remember the origin of the word “pixel”. “Pix” is a familiar abbreviation (one of many in United States English) which refers to a movie or to a photograph, both of which are also called “pictures”. “El”, is short for “element”.[iii] The colored napkins, then, as well as the embroidered stitches, are elements with which the artist reconstructs a mechanical image.

By just describing Mónica Bengoa’s technical procedures, certain paradoxes become evident. The image is that of a recognizable household scene, but it is enormous, blown up far over its “natural” scale. Yet its surface is made of innumerable small elements, none of them an image in itself, barely an image element. The enormous image is photographic, which means infinitely reproducible, lacking an “original” to refer to and thus lacking the aura of the unique, and any trace of the artist’s handiwork. Its elements are nonetheless small, handcrafted; the paper napkins even bear the marks of the cloth on which they were placed when they were being hand-colored. The large and the small, the mechanical and the handmade, are both absent and present, affirmed and contested. The work builds on paradox; it stages paradox.

On the undecidable [iv]

This Bengoa mise en scène –as personal as it is– corresponds to a more general moment of art, which wanders away from binary oppositions: mechanical reproduction vs. handicraft, for example. Perhaps it has more to do with a form of contemporary thought in which paradox is given free play, and there is no intent of resolving the oppositions paradox implies.[v] (That was what I meant with “staging” both poles, playing with their possible relations, refusing an opposition that tends to privilege one and to obliterate the other.)

The work creates a scene for the undecidable, and its strength lies then in deconstructing oppositions, indefinitely suspending their resolution and preferring strangeness –the effect of estrangement– to any truth effect.[vi] Creating strangeness is her particular way of rendering visible that which, out of habit, we no longer see. Curiously enough, what is thus rendered visible is what “supports the regulated actions that mark our days”, according to the artist: that is, objects we use every day. “The attention I have put on certain objects we use daily is based on how little we actually feel their presence in our everyday life, at least in conscious terms”, she adds.[vii]

In conscious terms… Poetry, Armando Uribe once said, is an expression of the unconscious. Maybe not only that; but in art and poetry work is done on the very brim of the unconscious. And we approach such a scene with the oscillating movement required by what is undecidable and paradoxical.

“Al son de un suave y blando movimiento” [viii]

Bengoa’s story, at the end, speaks of a soft movement. When describing how her mural is created and put on the wall, she points out that only the upper part of the napkins will be stuck to the wall, so that “they may move if there’s a draft.”

The mural is perceived as enormous, yet is made of very small elements that permit and include a subtle, occasional tremor in the large-scale image. As soon as it is perceived it has already ceased: like a sudden and fleeting chill, the soft motion of paper, a minimal allusion to something like tiny wings.

A great fixated image, then, which incorporates its own movement, registering something apparently not memorable, a child’s bedroom. (“What is memorable” –says a character in Jim Jarmusch’s film Mystery Train– “will always be remembered. What you have to register is the insignificant.”)

The everyday and its subtle differences

This work, enero 7:25 / january 7:25, is part of an “exploration on the staging of everyday family life”, the artist says. As part of that exploration her previous works were mural installations of many photographs of her small children (“an extension of my own skin”) sleeping on different nights (En vigilia / Wakefulness), or brushing their teeth in successive days (En vigilia IV / Wakefulness IV). The photographs were apparently the same or very similar, their differences were sometimes very subtle, or, to use the term proposed by Duchamp, inframinces –infrathin (or ultrassotile in Italian…) It refers to the almost unperceivable difference between two apparently identical objects. “In time” Duchamp wrote, “the same object is not the same after a 1 second interval” –“what relations with the identity principle?”[ix] Remember Bengoa’s story: the minimal difference between her and “her, herself, sitting, watching her”, is infrathin, in that same sense. “I think”, Duchamp would also write, rather enigmatically, “that through the infrathin it is possible to go from the second to the third dimension.”

This shift towards another dimension (and the ensuing strangeness) also happens with subtle differences in these works, and in Sobrevigilancia / Oversurveillance (2001), which –through other media, this time using 9.160 dyed thistle flowers– creates an enormous mural showing the sink seen in En Vigilia IV / Wakefulness IV. The life in question here is that of everyday practices –the everyday strangeness which is covered by the surface of the image, and that reveals itself in its tremors and fragmentations. The strangeness of “specific operations –ways of doing– a different spatiality (…), an opaque and blind movement” which escapes “the imaginary totalization performed by the eye”, Michel de Certeau says in his The Practice of Everyday Life (L’invention du quotidien).[x] Only the totalization performed by the eye creates the illusion of being able “to look”. The fiction of knowledge is that of being only this viewing point, a point in which the power of seeing converges. Everyday life, the friction it constantly creates, is constantly exposing this as merely make-believe, a simulacrum.

In enero, 7:25 / January, 7:25 Bengoa creates a mise-en scène in which this “theoric” (e.g., visual) simulacrum is implicitly likened to, say, viewing a map. The large image –fragmented, dispersed, potentially shaky, and joined in the next room by the small, embroidered pixel-stitches, becomes something not to be looked over, but something to be walked in and walked through. The large image, hyperreal, bathed in artificial light, –but made of fragments and minimal differences– points at something else than its own light, whose fascination is akin to that of a computer screen. It manages to suggest something that is never that clear, which remains below the thresholds of visibility, and is contained in the intertwined textures of everyday practices.

The exhausting task of remaining awake and overvigilant, of “not losing sight of where you are passing”, in the words of the artist herself, is to keep seeing the dense strangeness implicit in everyday practices. It means a dedication to studying the “texturology” (the word is de Certeau’s), of the practices that “invent” everyday life: knowing “the conditions of sleeping, eating, cooking, getting dressed, brushing one’s teeth, etc.” the artist says. Attention is put on suggesting what de Certeau calls “l’invention du quotidien” a creativity described by him as “disperse, tactical and bricoleuse” that in multiple surreptititious ways gives form to everyday life. The course of such creativity is not included in any map or general view. The knowledge it implies is as blind as that obtained in love’s body-to-body contact. The work presents a hyperrealistic image which contains, suggests, arouses something not presentable: its own blindness, maybe; that which remains outside the light of the large image composed of small handicrafts that would disappear on any screen.

The everyday: truth as project and as resistance

The subtle poetics in these works by Mónica Bengoa… Maybe the run of this text has made it possible to suggest one or two hypotheses for future conversations, for future spaces of encounter.

There is the question of truth. “To know if it is Right or Wrong we have a very simple rule: the composition must be true… We have to describe what it is, what we see, hear, do.”[xi] Notebook in hand, the artist produces like the twins in the book entitled El gran cuaderno. Everyday life: that which is, what we see, what we hear, what we do, our practices. In which world? The one of “hyperreal” TV and computer screen simulacra, of digitalized images, in which reality disappears into its amazing resemblance to itself?[xii] What kind of sight, of hearing, what other senses willallow access to the truth today?

If these questions cannot be answered properly, it is because they are rhetorical: they imply their own answers –and those are contained in the suspicion, the doubt facing the possibility of describing” what it is, what we see, hear and do.” Bengoa’s work can be seen as a continuing activity headed towards sharpening the senses (of which there may be others, complementary to the proverbial five). It is about being able to see not only a totalizing and dazzling image. It is about working on that image, that false image of the everyday, time and time again: questioning it from the inside, from the infrafine differences that conform it and for which it functions as cover-up. The access to what we really see, hear and do is not a given. On the contrary, it is a project.

The area of work in this project is most private: one’s own skin. (We already know that her children are also “my own skin” for her). With one’s hands. On the brim of the unconscious. On the brims of experience, if one can talk about experience. Facing the difficulty of approaching (from a prudent distance, softly) one’s own subjective dimension, which implies both living and looking at oneself while living, both existing and slightly differing existence. The work is done against an impoverishment of sensorial experience and of the relation to the world when the world is dominated and absorbed by technical media. A “micro resistance”[xiii] in everyday life, through the feminine and the maternal –is proposed as alien and subversive to common clichés. It is a profoundly meditative practice, alert to the subtle and apparently anonymous operations relating to the “contention structures” which the artist sees in the reiterative gestures of everyday life. The manual craft serves as a clue and as a trace of that micro resistance, and bears witness to the existence of different, “other” timings, of different, “other” forms of movement.

enero, 7:25 / January, 7:25 turns the Gabriela Mistral gallery into the “current working space” where the project is displayed not only in physical terms but also in relation to a particular reception and exhibition context. Here (in one of this city’s “interstices”), Mónica Bengoa plays out not only her own project, but also some of the more contemporary concerns of art the world over. The viewer is invited to share in an exploration of the real in a time of hyperrealities, of the everyday in terms of research and work-in-progress, of the fine points of a “necessary instability”, of a suspension and differing, which should keep us “sufficiently alert, so we don’t stumble and fall”, in the artist’s own words.

Adriana Valdés. October 2004

[i] “Lejana/Far away” in Bestiario/Bestiary, first published in 1951.

[ii] Poèmes saturniens: “Ni tout a fait la même ni tout a fait une autre”

[iii] Nicholas Mirzoeff, An Introduction to Visual Culture, New York and London, Routledge, 1999, p.30.

[iv] A small homage to Jacques Derrida, whose death we lament while writing this text.

[v] My thanks to Ticio Escobar for a luminous conference he gave on the subject this year in Sao Paulo, as part of a cycle entitled “Zonas de resistencia/Zones of resistance”, during the 26th Biennial.

[vi] When saying “estrangement effect” I cite Victor Chlovski´s well-known text “L’art comme procédé´” in Théorie de la littérature, Textes des Formalistes russes réunis, presentés et traduits par Tzvetan Todorov, Paris, Seuil, pp.76-97.

[vii] Mónica Bengoa, quoted in Transferencia y densidad, Tercer período, 1973-2000/Transference and density, Third period, 1973-2000, Santiago de Chile, Museo de Bellas Artes/Fine Arts Museum, 2000, p. 97.

[viii] “Going along the gentle and soft movement”. From the poem “Gladiolos juntos al mar/Gladiolos by the Sea”, by Chilean poet Óscar Hahn.

[ix] Marcel Duchamp, Notes, translated by Paul Matisse, Boston, G.K. Hall&Co., 1983, cfr. pp.1-46.

[x] L’invention du quotidien, chapter 7, Marches dans la ville: “Voyeurs ou marcheurs”. The following text is greatly indebted to De Certeau.

[xi] In Mónica Bengoa, Cuaderno en mano/Notebook in hand. It is a quote from the Agota Kristof novel The Notebook.

[xii] Cfr. Jean Baudrillard, cited in Art in Theory, 1900-1990, Edited by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, Blackwell, 1992, p.1050.

[xiii] Nicolas Bourriaud, “Les utopies de micro-proximités”, Spirale No.182, January-February 2002.

(I would like to write a text as fine as your work), in Solo exhibition catalogue enero, 7:25, p.16-30. Santiago, Chile. 2004