“En la fotografía existe una realidad tan sutil que se vuelve más real que la realidad misma.”

–Alfred Stieglitz

“¿Es pasión lo que somos? ¿Lo que somos está en fotografías? ¿Es casi real aquello que somos en fotografías? Quizás se ha vuelto lo más real.”

–Richard Prince

I. El museo y la selfie

Esta es una historia verdadera, o debería decir, “real”. En el verano de 2016, mi esposa, mi hijo adolescente y yo cambiamos las indolentes playas y el sol abrasador de los territorios sureños de España por las temperaturas más frescas de París y sus kilómetros de pinturas, esculturas y monumentos culturales. Tras aterrizar en el aeropuerto de Orly, rápidamente guardamos nuestros bolsos con el conserje del hotel y procedimos a toda prisa a la Place du Carrousel y su imponente ex palacio de la realeza, el Louvre. Es aquí precisamente en donde encontramos un inesperado problema filosófico: el problema de lo real.

Gracias a la magia de mi esposa con mi pase de prensa, atravesamos desvergonzadamente una maraña de turistas. Pero apenas llegamos al mesón dicho problema comenzó a manifestarse agudamente. Eran poco después de las nueve de la mañana y la fila de visitantes insatisfechos ya serpenteaba alrededor del lobby como una fila del pan. Extrañamente, la molestia de los visitantes era más evidente en sus manos que en sus rostros. Jugueteaban sin detenerse con sus IPhones y dispositivos Android, texteando, twiteando, facebookiando y, por supuesto, tomando infinitas fotografías.

Estoy, sin duda, tan familiarizado con la cultura de las celebridades como cualquier otro ser humano del siglo veintiuno, pero nunca antes había visto a docenas de personas empujando y atropellándose para obtener fotografías de ellos mismos frente a un simple letrero de museo: este anunciaba la entrada al “Musee du Louvre”. Las cosas se volvieron aún más extrañas al llegar al arte al interior del museo. El Apolo de Belvedere estaba tan atestado que era literalmente inalcanzable; la Venus de Milo estaba rodeada de cientos de personas dando empujones, blandiendo bastones selfie como antenas; la sala que contiene a la Mona Lisa estaba atascada por barreras de metal idénticas a las que arrean a los visitantes a través de inmigración en el aeropuerto. Hordas haciendo fila, esperando una oportunidad de acercarse al famoso retrato de Leonardo y poner cara de pato frente a sus teléfonos.

Observar este fenómeno bizarro me hizo plantearme una cantidad de preguntas urgentes. Entre las menos inflamatorias estaban: ¿Qué hace que las personas confundan una rápida instantánea de ellos mismos con una experiencia en sí? Como la selfie, ese acto relativamente nuevo de auto-documentación consistente en que una persona se toma una fotografía a sí mismo/a para subirla a las redes sociales, en efecto, ha adquirido un estatus equivalente o superior al evento, lugar u objeto que es fotografiado. También, ¿qué tan profundamente ha cambiado la mediación de dispositivos electrónicos como cámaras, computadores y teléfonos celulares la manera en la que vemos el mundo?

Una respuesta general es que el sentido de la vista en sí mismo se ha vuelto, en el lenguaje de los sociólogos culturales, profundamente aculturizado. Esto significa, principalmente, que las personas comunes, no solamente aquellas bajo el influjo de París, los turistas como lemmings Noruegos, progresivamente hoy ven la realidad a través de la intervención de un exceso de dispositivos. Esta aculturación, como la mayoría de los artistas importantes han sabido durante décadas, le debe su condición a la omnipresencia de la fotografía. Aquella invención del siglo diecinueve ha transformado la realidad, tanto gradual como completamente, de formas con las cuales aún estamos intentando lidiar.

Como escribió el crítico de fotografía Andy Grundberg en su brillante libro acerca de la fotografía y el postmodernismo, La crisis de lo real, las invenciones de rápida evolución han alterado fundamentalmente nuestra manera de ver. Pero más que seguirse a modo de generaciones sucesivas, estos así llamados avances se apilan como estratos geológicos extremadamente porosos. La siguiente cita pone el tema en pocas palabras: “Parece imposible hoy en día que alguien pueda tener una experiencia directa, sin mediar, del mundo. Todo lo que vemos es visto a través del caleidoscopio de todo lo que hemos visto antes”.

II. La artista hace las preguntas correctas

La artista chilena Mónica Bengoa ha convertido el hacer preguntas fundamentales –ilustradas de manera intensamente visual– acerca de lo que es y no “real” acerca de las imágenes, en el trabajo de su vida. Su arte, entre otras cosas, consiste en una crítica de nuestras maneras tradicionales de ver, pero también entrega una reflexión en evolución acerca de la representación en sí. Esa representación, como una artista como Bengoa sabe, es llevada adelante primordialmente por el medio de la fotografía. La lingua franca de las imágenes contemporáneas, la fotografía efectivamente representa (y mal representa) al mundo moderno, de la publicidad al cine digital, del fotoperiodismo a Youtube, y aún así sus estructuras permanecen mayoritariamente invisibles gracias, más que nada, a la ubicuidad del medio.

Bengoa lleva adelante la tradición de una cantidad de post-conceptualistas bien conocidos del tardío siglo 20 –artistas tan variados como John Baldessari, David Hockney, Chuck Close y Cindy Sherman–, mientras que investiga un campo representacional en expansión que permanece al menos tan impugnado y problematizado como en los 70s y 80s. Notablemente, ese mismo campo está ahora inundado con un número aún mayor de imágenes; una situación que, para ciertos artistas, demanda más en vez de menos reflexión histórica. Si las obras intensamente manuales, basadas en la fotografía de Bengoa muestran una constante híper-conciencia acerca de existir dentro de una cultura ligada a las cámaras –una conciencia que es idéntica a la de muchos artistas postmodernos canónicos–, su alerta a esa condición evita antagonismos simplistas.

Una pionera remota en el campo de la realidad cotidiana y su leve relación con la imagen contemporánea, la artista chilena, desde el principio de su carrera, consistentemente ha enfrentado procesos fotográficos cada vez más inestables con la solidez testaruda de las manualidades tradicionales. En obras tempranas como Sobrevigilancia (2001) y Ejercicios de Resistencia: Absorción (2002), en el que la artista compuso imágenes monumentales de interiores domésticos derivados de instantáneas caseras usando, respectivamente, flores secas y servilletas de restaurante, sus resultados mapean las fallas del medio. Presentados como disfrazados de arduas reinterpretaciones, sus versiones XL de reproducciones mecánicas de modesta escala literalmente materializan (¿o re-materializan?) la conexión cada vez más efímera de la fotografía con lo real.

Corresponde aquí un punto aclaratorio: Bengoa investiga la fotografía por varias razones fundamentales. Primero, porque el medio es la moneda común de intercambio cultural. Segundo, ella explora la esencia del medio, porque la fotografía es, como todos saben, un medio explícitamente reproducible. Una tercera razón tiene que ver con el hecho de que la vasta mayoría de los fotógrafos del mundo evitan el aura histórica de “arte” y “autoría”, exactamente las propiedades auráticas que la teoría postmodernista ha rechazado consistentemente en medios como la pintura y la escultura. Por último está la inmersión cotidiana de la artista en la vida contemporánea: imágenes de la TV, películas, publicidad, mercadeo corporativo, relaciones públicas y, cada vez más, las redes sociales.

Mientras que la cultura popular no ha inspirado directamente el trabajo artístico de Bengoa a la fecha, es innegable que la industria global de la producción en masa de imágenes ha ayudado a formar la perspectiva de esta artista frente a las propiedades en expansión y omnipresentes de la reproducción mecánica.

La intención de Bengoa al examinar las posibilidades representacionales de la fotografía, debemos decir, no es convertirse en fotógrafa, ni aliar su práctica notablemente reflexiva con la tradición artística del medio. En vez de eso, su exploración de imágenes fotográficas cotidianas usa el medio como un trampolín o punto de partida para investigar otros medios y materiales, incluyendo papel, fieltro, flores secas, bordado y libros, mientras invoca una manera actualizada de conceptualismo forense, orientada epistemológicamente. Su acercamiento favorece el método riguroso por sobre la expresión artística; los resultados, impresionantes, nunca dependen de la maestría técnica o la veracidad como argumentos para la persuasión visual.

“No me interesa pintar sobre tela, ya que pienso que eso puede alienar a los espectadores al mostrarles algo que ellos son incapaces de hacer”, Bengoa reveladoramente le dijo al diario El Mercurio en víspera de su presentación en la Bienal de Venecia el 2007. “Siempre he pensado que cualquiera con la paciencia suficiente podría ejecutar mi obra; no tiene nada que ver con talento o tener una buena mano”.

No sorprende entonces que Bengoa vuelva a recurrir al minimalismo para su excursión en la Bienal de Venecia. Titulada Some Aspects of Color in General and Red and Black in Particular (Algunos aspectos del color en general y del rojo y negro en particular), en referencia al último texto escrito por Donald Judd antes de su muerte en 1993, los cuatro grandes murales emplearon cardos, teñidos en varios tonos de rojo y negro para presentar otro cuidadoso análisis de la fotografía. Esta vez su examinación se centró en el interés de la artista en los efectos de la macrofotografía. Cada mural presentaba imágenes en primer plano de insectos, como las que uno podría encontrar en un libro de entomología. Aumentados a proporciones no naturales, los sujetos de la artista aparecían monstruosos, no a tamaño insecto; una impresión reforzada por las limitaciones cromáticas de los murales. Otro rasgo visual de la instalación de Bengoa se relacionaba a sus “pixeles” hechos a mano (como la artista se ha referido a sus unidades básicas de imagen): el hecho de que los cardos son flores funerarias proveía una metáfora lapidaria de ready-made para el valor documental muchas veces elogiado de la fotografía.

En una entrevista con el diario El Mercurio del 2007, Bengoa llanamente afirmó su posición como una artista relacionada con la fotografía tanto como medio y como fenómeno cultural envolvente: “El medio se vuelve el contenido de la obra en el minuto en que uno se para en algún lugar a ver algo. Esa distancia, me parece, le permite al espectador ver las cosas nuevamente. Una imagen puede posibilitar un encuentro con ciertas verdades visuales, pese a todas las posibilidades de manipulación digital que sabemos existen gracias a Photoshop”.

III. Una arqueología de imágenes

Una arqueóloga de la manera en la que vemos, los trabajos más recientes de Bengoa han extendido sus observaciones acerca de las limitaciones de la fotografía para revelar nuevos medios: imágenes de textos encontrados han sido representadas con nuevos materiales, entre ellos el fieltro y el bordado. Sus primeros experimentos en esta nueva modalidad empezaron el 2010 con una obra que ella nombró Einige Beobachtungen über Insekten: Langhornbiene (Eucera longicornis) o Algunas consideraciones acerca de los insectos: Abeja de antenas largas (Eucera longicornis).

Una obra envolvente que presentó el uso de enciclopedias de historia natural en alemán; Bengoa fotografió esos libros de flora y fauna para traducir sus textos e imágenes en tapices de gran escala. Durante el proceso, las distorsiones de la cámara, tanto del texto como de la imagen, fueron hechas ineludiblemente físicas (consideren, por ejemplo, los efectos de la falta de enfoque, ángulo de cámara o poca profundidad de campo).

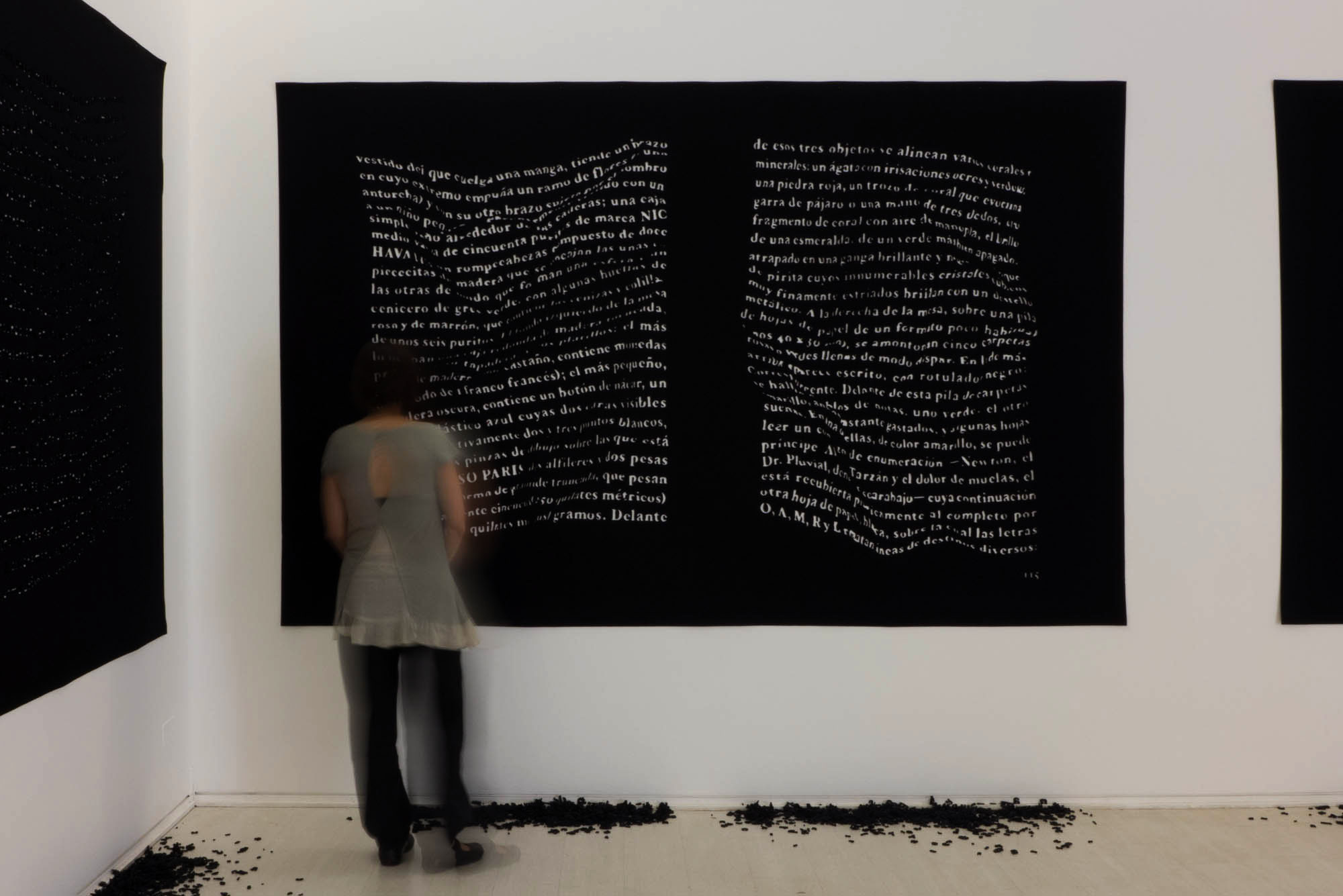

De ahí, Bengoa siguió con su más reciente experimento: una instalación basada en la fotografía del tamaño de una habitación. Tomando prestado del canon postmoderno, puntualmente una sección de Lo infraordinario de Georges Perec en la cual el autor detalla múltiples ítems de su escritorio, Bengoa transformó lo que es esencialmente un listículo literario en una plantilla y entonces en un ambiente de imágenes en cuatro partes, cortado en negativo de distintos trozos de fieltro color carbón.

El efecto final de la obra, que ella tituló Still Life/Style Leaf (naturaleza muerta/hoja de estilo) (2014), resalta la relación ecfrástica de la fotografía con el mundo mediante su legitimización. Al materializar no solamente un texto, sino un dispositivo literario inmemorial como una imagen envolvente, Bengoa le da forma física a su máxima ambición artística: “referirse a lo que usualmente pasa desapercibido, pero que aún así es una parte vital de nuestra relación con el mundo a nuestro alrededor”. Puesto de otra forma: la obra de Bengoa ha estado largamente dedicada a hacer a la fotografía y sus soportes técnicos más, en vez de menos, visibles.

Bengoa ha tomado prestadas estas y otras imágenes de lo que Perec ha llamado “lo infraordinario” permitiendo una extensa examinación no solo de aspectos habituales de la vida cotidiana, esos eventos y cosas que no son ni banales ni exóticas, pero también de la maquinaria oculta que registra o, alternativamente, decide no registrar e incluso mal-representar, lo que los seres humanos experimentan como real y significativo. Son precisamente esas experiencias, argumenta la artista, las que a menudo son eclipsadas por la ubicuidad en expansión de la fotografía.

Como Roland Barthes escribe en La cámara lúcida, las fotografías declaran que lo que uno está mirando realmente existió, no como realidad, sino como metáfora. Aún así, resulta en nuestros tiempos que esa certeza se ha desdibujado. Más que hacer que la fotografía encarne “la presencia de una cosa”, el medio que Barthes examinó en 1980 se ha vuelto cada vez más susceptible a la manipulación, a lo que los comentaristas contemporáneos llaman “contextualidad”, a la lisa y llana falsificación (como en “fake news”, noticias falsas o falaces) y a un ataque viral de narcisismo fotográfico (la selfie) de una manera como ni el mundo ni la historia de la manufactura de imágenes han visto jamás.

En esta nueva distopía de la imagen el mundo necesita artistas como Mónica Bengoa, figuras que toman una cuidadosa medida de nuestro mundo de imágenes y la informan inteligente y desapasionadamente y con una percepción poco común. Su investigación extensa y visualmente poderosa es declarada sobre la noción de que la vida es un edificio, el que construimos, en parte, para esconder sus fundaciones, pero también sobre la idea de que la diferencia entre un edificio y una ruina quizás sea difícil de detectar.

Brooklyn, 2017

Christian Viveros-Fauné

Escritor, curador y crítico de arte

Publicado en m. [una tentativa de inventario exhaustivo, aunque siempre inconcluso], Santiago, Chile. Ediciones EUONIA, p. 133-136. 2017.

“In photography there is a reality so subtle that it becomes more real than reality”

—Alfred Stieglitz

“Is passion what we are? Is that what we are in pictures? Is what we are in pictures almost real? Maybe it’s become the most real thing.”

—Richard Prince

I. The Museum and the Selfie

This is true story, or should I say a “real” story. In the summer of 2016 my wife, my teenage son and I swapped the indolent beaches and blistering sun of Spain’s southernmost territories for Paris’ cooler temperatures and its miles of paintings, sculptures and cultural monuments. After landing at Paris Orly, we quickly stashed our bags with the hotel’s concierge and proceeded, post haste, to the Place du Carrousel and its imposing ex-palace of kings, the Louvre. This was precisely where we encountered an unexpected philosophical conundrum: the problem of the real.

Thanks to my wife’s wizardry with my press pass, we shamelessly cut through a thicket of fellow tourists. But no sooner had we reached the ticket counter than said problem began to manifest itself acutely. It was barely nine in the morning and already the queue of dissatisfied visitors snaked around the lobby like a bread line. Oddly, the guests’ annoyance was more evident in their hands than on their faces. They fidgeted endlessly with Iphones and Android devices, texting, twittering and Facebooking—and, of course, taking endless pictures.

I am, no doubt, as familiar as the next 21st century human with celebrity culture, but I had never before seen dozens of people pushing and shoving to get pictures of themselves in front a simple museum sign: this one announced the entrance to the “Musee du Louvre”. Things got even stranger when we reached the art inside the museum. The Apollo Belvedere was so thronged it was literally unreachable; the Venus de Milo was surrounded by hundreds of jostling people brandishing antenna-like selfie-sticks; the room containing the Mona Lisa was jammed by metal barriers identical to those that herd visitors through airport immigration. Hordes queued there, waiting for an opportunity to approach Leonardo’s famous portrait and make duck lips into their phones.

Watching this bizarre phenomenon prompted a number of urgent questions. Among the less inflammatory were: What makes people mistake taking a quick snapshot of themselves with an actual experience? How has the selfie—that relatively new act of self-documentation which consists of a person taking a picture of him or herself to post to social media—effectively acquired an equivalent or superior status to the event, location or thing that is photographed. Also, how profoundly has the mediation of technological devices like cameras, computers and mobile phones changed the way we see the world?

One general answer is that sight itself has, in the parlance of cultural sociologists, become deeply acculturated. This means, chiefly, that everyday people, not just Paris-addled, lemming-like tourists increasingly see reality through the intervention of an ever-growing glut of devices today. This acculturation—as most important artists around the world have known for decades—owes its condition to the ubiquity of photography. That 19th century invention has transformed reality both gradually and completely in ways that we are still coming to grips with.

As the photography critic Andy Grundberg wrote in his brilliant book about photography and postmodernism, The Crisis of the Real, the rapidly evolving innovations of our time have fundamentally altered our way of seeing. But rather than follow each other like succeeding generations, these so-called advances instead pile up like extremely porous geological strata. The following quote puts the issue in a nutshell: “It seems impossible in this day and age that one can have a direct, unmediated experience of the world. All we see is seen through the kaleidoscope of all that we have seen before.”

II. The Artist Asks the Right Questions

The Chilean artist Mónica Bengoa has made it her life’s work to ask fundamental and intensely visually literate questions about what is and is not “real” about images. Her art, among other things, consists of a critique of our conditioned ways of seeing, but also provides an evolving reflection on the nature of representation itself. That representation, an artist like Bengoa knows, is carried on primarily by the medium of photography. The lingua franca of contemporary images, photography effectively represents (and misrepresents) the modern world—from advertising to digital film, from photojournalism to Youtube—yet its structures remain mostly invisible thanks mostly to the medium’s ubiquity.

Bengoa carries on the tradition of a number of better known late 20th century postconceptualists—artists as varied as John Baldessari, David Hockney, Chuck Close and Cindy Sherman—as she investigates an expanding representational field that remains at least as contested and problematized as it was back in the 1970s and ‘80s. Notably, that same field is now flooded with an even greater deluge of images; a situation that, for certain artists, demands more rather than less historical reflection. If Bengoa’s intensely manual, photo-based artworks exhibit a constant hyper-awareness about existing within a camera-bound culture—an awareness that is identical to that of many canonical postmodern artists—her alertness to that condition avoids facile antagonisms.

A far-flung pioneer in the field of quotidian reality and its tenuous relationship to the contemporary image, the Chilean artist has, since the beginning of her career, consistently pitted increasingly unstable photographic processes against the stubborn solidity of traditional arts and crafts. In early artworks such as Sobrevigilancia (Over Vigilance) 2001, and Ejercicios de Resistencia: Absorción (Resistance Exercises: Absorption), 2002—in which the artist composed monumental images of domestic interiors derived from homely snapshots using, respectively, dried flowers and restaurant napkins—her results map out the shortfalls of the medium. Presented in the guise of labor-intensive reinterpretations, her XL versions of modestly scaled mechanical reproductions literally materialize (or is that re-materialize?) photography’s increasingly ephemeral connection to the real.

A point of clarification is in order here: Bengoa investigates photography for several fundamental reasons. Firstly, she does so because the medium is the common coin of cultural image exchange. Secondly, she explores the medium’s quiddity because photography is, as everyone knows, an explicitly reproducible medium. A third reason has to do with the fact that the vast majority of the world’s photographs avoid the historical aura of “artistry” and “authorship”—the exact auratic properties that postmodern theory has consistently rejected in media like painting and sculpture. Lastly, there’s the artist’s everyday immersion in contemporary life: images from TV, films, advertising, corporate branding, public relations and, increasingly, social media.

While popular culture has not directly inspired Bengoa’s artwork to date, there is no denying that the global industry of mass-image making has helped shape this artist’s outlook on the expanding and omnipresent properties of machine reproduction.

Bengoa’s intention in examining the representational possibilities of photography, it should be said, is neither to become a photographer herself nor to ally her remarkably reflexive practice with the medium’s fine art tradition. Instead, her exploration of everyday photographic images use the medium as a trampoline or jumping off point to investigate other media and other materials—these include paper, felt, dried flowers, embroidery and books—while invoking an up to date, epistemologically oriented brand of forensic conceptualism. Her approach favors rigorous method over artistic expression; the results, impressive as they are, never rely on technical mastery or truthfulness as arguments for visual persuasiveness.

“I’m not interested in painting on canvas, since I think that can sometimes alienate viewers by showing them something that they are incapable of doing,” Bengoa tellingly told the Chilean newspaper El Mercurio on the eve of her Venice Biennale presentation in 2007. “I always thought anyone with enough patience could execute my work; it’s got nothing to do talent or having a great hand.”

No wonder then, Bengoa cast back to the father of Minimalism for her Venice Biennale outing. Titled Some Aspects of Color in General and Red and Black in Particular—in reference to the last text written by Donald Judd prior to his death in 1993—Bengoa’s four large murals used thistles, dyed various shades of red and black, to present yet another careful analysis of photography. This time her examination centered around the artist’s interest in the effects of macro-photography. Each mural presented close-up images of insects, like one might find in a book on entomology. Blown up to unnatural proportions, her subjects appeared monstrous, not insect-sized; an impression reinforced by the murals’ chromatic limitations. Another visual feature of Bengoa’s installation concerned her handmade “pixels” (the artist has on occasion referred to her basic image units as “pixels”): the fact that thistles are funerary flowers provided a ready-made lapidary metaphor for photography’s much vaunted documentary value.

In her 2007 interview with El Mercurio, Bengoa flatly stated her position as an artist vis a vis photography as both a medium and an all-enveloping cultural phenomenon: “The medium becomes the work’s content the minute you stand somewhere to look at anything. That distance, it seems to me, allows the viewer to look at things anew. An image can make possible an encounter with a certain visual truths, despite all of the possibilities for digital manipulation that we know exist thanks to Photoshop.”

III. An Archeology of Images

An archeologist of the way we see, Bengoa’s more recent works have extended her observations about the limitations of photography to several new media: images of found text have been rendered with new materials, among them felt and embroidery. Her first experiments in this new modality began in 2010 with a work she lengthily titled Einige Beobachtungen über Insekten: Langhornbiene (Eucera longicornis) or Some considerations on insects: Long-horned Bee (Eucera longicornis).

An enveloping work that featured the use of German-language encyclopedias of natural history, Bengoa photographed these books of flora and fauna in order to translate their text and pictures into large-scale tapestries. In the process, the camera’s distortions of both text and image were made inescapably physical (consider, for example, the effects of lack of focus, camera angle and shallow depth of field).

From there, Bengoa moved onto her newest experiment: making a room-sized photo-based installation using nothing but cloth and text. Borrowing from the postmodern canon—namely, a section of Georges Perec’s book The Infraordinary in which the writer recursively itemizes multiple items on his desk—Bengoa transformed what is essentially a literary listicle first into a stencil, and then into a four part image environment sliced out negatively from separate lengths of charcoal-colored felt.

The final effect of the work, which she titled Still Life / Style Leaf (2014), underscores photography’s ekphrastic relationship to the world by literalizing it. By materializing not just text but an age-old literary device as an enfolding image, Bengoa gives physical form to her ultimate artistic ambition: “to address what commonly passes unnoticed, that which does not seem to have any relevance, but nevertheless is a vital part of our relationship with the world around us.” Put another way: Bengoa’s oeuvre has long been devoted to make photography and its technical supports more, rather than less, visible.

These and other images Bengoa has borrowed from what Perec has termed “the infraordinary” allow for an extensive examination not just of habitual aspects of everyday life, those events and things that are neither banal nor exotic, but also of the hidden machinery that records—or, alternately, chooses not to record and even misrepresents—that which human beings experience as real and meaningful. It is precisely those experiences, the artist argues, that are often obscured by photography’s expanding ubiquity.

As Roland Barthes writes in Camera Lucida, photographs declare that what you’re looking at really existed, as actuality, not as metaphor. Yet, it turns out, in our time even that certainty has slipped away. Rather than have photography incarnate “the presence of a thing,” the medium Barthes surveyed back in 1980 has become increasingly susceptible to manipulation, to what contemporary commentators call “contextuality,” to outright falsification (as in “fake news”) and to a viral attack of photographic narcissism (the selfie) unlike anything the world or the history of image-making has ever seen before.

In this new image dystopia the world needs artists like Mónica Bengoa—figures who take careful measure of our image world and report back intelligently, dispassionately, and with rare insight. Her extensive and visually powerful research is predicated on the notion that life is an edifice, which we build, in part, to hide its foundations—but also on the idea that the difference between an edifice and a ruin may be hard to detect.

Brooklyn, 2017

Published in m. [una tentativa de inventario exhaustivo, aunque siempre inconcluso], Santiago, Chile. Ed EUONIA, p. 133-136. 2017.