Las conexiones entre arte y vida están entre los temas más perdurables del arte a través del siglo veinte. Los artistas siguen reinventando las morfologías, tipologías, sintaxis y modos visuales de formas aparentemente ilimitadas que le permiten al espectador percibir a las personas comunes, vistas y objetos con una visión fresca y un entendimiento nuevo [1]. Mónica Bengoa es una artista contemporánea cuyo excepcional trabajo nos ha hecho pensar nuevamente acerca de la importancia de la actividad, evento, lugar y artefactos cotidianos como temas del arte. Bengoa privilegia las tareas u ocupaciones rutinarias de las personas que tal vez, si no fuese por su presentación o construcción artística, pasarían inadvertidas simplemente por ser tan mundanas.

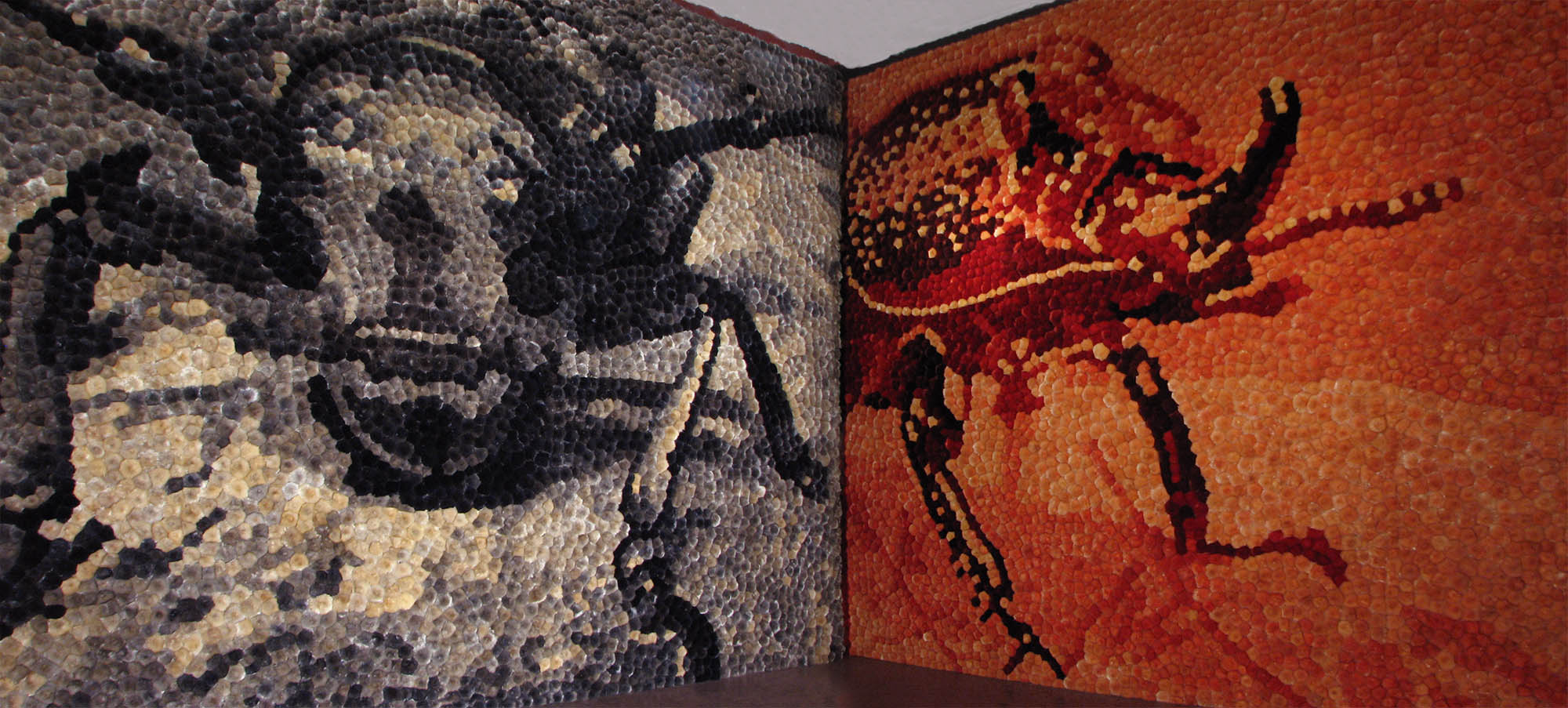

La instalación Some Aspects of Color in General and Red and Black in Particular / Algunos aspectos del color en general y del rojo y negro en particular de Bengoa en la 52 Bienal de Venecia consiste en cuatro grandes murales construidos a partir de 28.000 flores de cardo que recrean anatomías de insectos, que al ser proyectadas sobre las murallas funcionan a modo de dibujos a gran escala. La artista entonces cubre meticulosamente cada detalle de las anatomías de insecto con miles de cardos, dejando sus contornos apenas visibles. Las variaciones tonales dentro de la masa floral –doce rojos en dos de las imágenes y diez grises y negros en las otras dos– crean un sentido de profundidad, textura y placer sensorial, así disfrazando la atemorizante apariencia de las imágenes gigantescas que uno posiblemente asociaría con películas de terror.

El trabajo de Bengoa durante los nueve años previos expande las lecciones del minimalismo y post minimalismo: repetición y cuadrícula; y el toque de la artista, énfasis sobre lo hecho a mano y la importancia de las referencias (auto)biográficas. Sus instalaciones murales a gran escala son un estudio en contra-expectativas. Aunque efímera, su producción es de un trabajo intenso. La obra es visualmente elaborada y a pesar de su duración sobre el muro, sigue siendo un objeto artístico tradicional.

En The Color of the Garden / El color del jardín de 2004 por ejemplo, Bengoa tomó fotografías de plantas sobre los vanos de sus ventanas, vistas de su balcón y su sala de estar, áreas de su dormitorio con su cama y mesa de noche, la sala de estar con un sofá, libros, fragmentos de obras, y puertas –abiertas y cerradas. Estas imágenes constituyen una escena compuesta, pero no lineal del espacio vital interior de la artista, con vista hacia afuera [2]. Algunas de las imágenes fueron instaladas en la galería Latincollector en Nueva York como fotografías, y otras como murales a gran escala en los cuales las imágenes fotográficas fueron transferidas digitalmente a pequeñas servilletas de papel y después coloreadas a mano, una a una, cubriendo toda la superficie. La artista usa cientos, algunas veces miles de servilletas sobre las cuales son unidos fragmentos de imágenes, originalmente capturadas por la cámara para formar una composición de gran tamaño.

Mónica Bengoa concibió una secuencia de instalaciones sobre el muro tituladas Kitchen de 2003-2004, que iba a representarla ejecutando labores en su cocina [3]. En los distintos lugares, cada escena efímera habría sido creada con aproximadamente 800 servilletas coloreadas a mano. En Ejercicios para el fortalecimiento del cuerpo / Exercises in Strengthening the Body de 2002, las fotografías, impresas a inyección de tinta sobre papel de acuarela, son de la artista ejecutando escenas domesticas, y en Resistance Exercises / Ejercicios de resistencia de 2002 la artista representa utensilios de cocina comunes sobre miles de servilletas de papel. En Vigilia 4 / Vigil IV (2001-2002), Bengoa fotografió a sus hijos a diario durante siete meses mientras se lavaban los dientes en el lavatorio del baño. Las 640 fotografías de esa serie reafirmaron el agudo interés en la repetición obsesiva de rituales diarios como puntos de partida de su arte / diálogo vital.

Sobrevigilancia / Overvigilance de 2001 es una imagen ampliada del lavatorio del baño de la artista creada con 9.160 flores en tonos verdes para formar una imagen a tamaño muro. Ese trabajo es el precursor en términos de los materiales usados en los murales de la Bienal de Venecia. En En vigilia / Vigil de 1999, una temprana exploración de En vigilia IV, también se trata de una extensa serie de fotografías en las cuales la artista captura a sus hijos durmiendo cada noche por un periodo de cinco meses. Al final del proyecto, las 310 fotografías de sus hijos fueron diferenciadas una de otra por los pequeños cambios notados al moverse en su sueño. Tanto En vigilia IV y En vigilia forman un tipo de topografía de acciones diarias que definen las costumbres de sus hijos, y por extensión, las de cualquier otra persona en un determinado momento y lugar [4]. El interés de Bengoa en la repetición de rituales diarios no sólo sirve como punto de partida para su diálogo arte / vida, sino que lo define. De manera extraña estos rituales no son tan distintos de las extensas series de fotografías de Sophie Calle de tomas de camas desordenadas en una pieza de hotel que, a través del tiempo, registraron las posiciones de sueño de la anónima clientela del hotel. En el trabajo conceptual de Calle, sin embargo, el espectador nunca vio la figura durmiente, sólo las impresiones dejadas sobre las sábanas arrugadas. La identidad y las actividades de la persona fueron dejadas a la imaginación del espectador. En contraste, las series de Bengoa fueron de hecho documentos biográficos de sus hijos, cuya presencia fue fijada en un momento en el tiempo, imágenes que podrían pertenecer al álbum fotográfico familiar.

Críticamente, el trabajo de Bengoa nos fuerza a detenernos momentáneamente y reconsiderar nuestros propios espacios personales, su configuración y significado en nuestras vidas. También nos desafía a redefinir la manera en la cual usamos nuestro espacio, la manera en la cual nuestro espacio se refleja sobre nosotros a través de objetos que incluimos, disponemos y observamos. Algunos aspectos del color en general y del rojo y negro en particular se trata no tanto de las exploraciones de la artista respecto a su espacio privado y sus aspectos rutinarios, como de crear un espacio más público que de alguna manera empequeñece al espectador, casi hasta el punto de sentirse abrumado. Los materiales y procesos de Bengoa siguen siendo familiares, pero ha empezado a usar la cámara con fines distintos. En vez de capturar lo prosaico en casa en cientos de tomas secuenciales, captura unas pocas tomas macro del exterior prosaico, así ampliando nuestra percepción de la naturaleza.

La siguiente conversación entre Julia P. Herzberg (JPH) y Mónica Bengoa (MB) tuvo lugar a lo largo de varios meses en 2003. Es incluida acá, porque provee un entendimiento de los procesos y conceptos de la artista en su trabajo de instalación basado en la fotografía.

JPH: En algún momento del tamborileo monótono de rituales rutinarios como el dormir, lavarse o peinarse, has percibido un pulso vital (energía, un signo de vida). ¿Por qué te interesó capturar los momentos repetidos en las vidas de tus hijos?

MB: Mi trabajo se ha centrado esencialmente en poner en escena la vida cotidiana. He registrando consistentemente actividad y situaciones en el ambiente doméstico. He capturado a mis hijos como objetos de estas fotografías en situaciones que no son memorables, que no resaltan en la historia de una familia; más bien toman posesión porque no son distintivas sino solamente normales.

Creo que las rutinas domésticas se vuelven rituales que sostienen nuestra noción de identidad. A través de la repetición, las rutinas domésticas ritualizadas no sólo se tornan visibles sino que también establecen un marco temporal. Estoy interesada en enfocarme en estas rutinas debido a su naturaleza frágil y efímera. Y aunque las rutinas son fugaces, también proveen soportes estructurales en el espacio seguro del “hogar”.

JPH: Más actualmente, en Ejercicios de Resistencia: Absorción (2002), pareces haber hallado un tipo de poesía en la representación de objetos comunes de la cocina como ollas, sartenes y hornos. ¿Qué es lo que te lleva a retratar objetos comunes de la vida cotidiana? O dicho de otro modo, ¿Qué te inclina al acto de realizar tareas de la cocina como temática de tu arte?

MB: La atención que he puesto en ciertos objetos de uso cotidiano se basa principalmente en lo desapercibido de su presencia en nuestro accionar diario, al menos a nivel consciente. Al registrar estos objetos de cocina, decidí ejecutar tareas domésticas del tipo más rutinario, en un intento de crear un sentido de familiaridad para el espectador, quien puede a cambio relacionarse con este tipo de objetos.

En Ejercicios de resistencia: roce y Ejercicios de Resistencia: Absorción fotografié viejas cocinas en sencillos restoranes en el mercado popular La Vega, en el centro de Santiago. Estos trabajos estaban destinados a ser exhibidos en Boston y Nueva York. Por lo tanto, me pareció que debía ampliar mi noción de los objetos domésticos, desde mi casa hacia aquella otra aun mayor –la ciudad que habito. En el mercado encontré enormes ollas familiares y utensilios de cocina desgastados y muros de azulejos manchados con los restos de comidas pasadas. No estaba tan interesada en registrar los rasgos formales o funcionales de los utensilios de cocina como en capturar los rastros del uso constante.

JPH: Tú provienes de un fuerte antecedente en la impresión (fue tu especialización y ahora la enseñas en la Universidad Católica). Durante los últimos años (2001-2003) tu trabajo ha involucrado técnicas de impresión innovadoras. ¿Puedes describir los procesos que usarás en Cocina, una obra similar en cuanto a forma a Ejercicios de Resistencia: Absorción (2002), un mural para el cual usaste 1.330 pequeñas servilletas de papel?

MB: Durante los últimos dos años he cambiado los métodos y materiales que uso al transferir imágenes fotográficas completamente. Hice esto intercambiando materiales con otros medios y soportes, invirtiendo estrategias formales derivadas del dibujo y la pintura, e incluyendo el uso de objetos. Estos métodos me han permitido crear un dispositivo efectivo de transferencia para producir pinturas murales a gran escala hechos de objetos comunes de la vida cotidiana. La obra final mantiene la calidad reproducible de la estructura fotográfica original. Mi cercanía con la impresión me ha permitido expandir sus procesos e incorporar el frottage a mi obra, entre otras técnicas.

En las series Ejercicios de resistencia, las imágenes originales eran fotografías de utensilios de cocina populares que más tarde retoqué digitalmente para diferenciar las diversas áreas cromáticas. Tras re-dibujar cada zona de color específica, imprimí el contorno sobre las servilletas de papel. Tratando de ser fiel al referente cromático original, “coloreo” cada servilleta con crayones usando una técnica de frote (frottage) sobre el mantel de mi mesa, de manera de que la textura de la superficie es transferida hacia cada servilleta.

JPH: Me has hablado acerca de tu interés en enfocarte en los aspectos frágiles de los rituales diarios porque en ellos encuentras la posibilidad de construir un “hogar” nuevo. ¿Podrías definir qué quieres decir con construir un nuevo hogar?

MB: Mi proceso de producción involucra ir y venir, hacia y desde la casa. Estos cruces generan un cierto estado de suspensión que requiere que construya un caparazón protector en orden a sobrevivir estos tránsitos constantes, “llevar una casa sobre mi espalda”. Habiendo aprendido a sobrevivir ese pasaje constante de lugar a lugar (del hogar al museo), puedo establecer mi “taller del momento” en cualquier lugar nuevo.

[1] Entre los muchos artistas sobresalientes que nos han hecho volver a pensar en la importancia de lo común como un elemento definitorio del arte está primero Duchamp, después Warhol (n. 1928) y muchos de su generación, siguiendo con artistas conceptuales más recientes como Robert Wilson (n. 1941), Hanne Darboven (n.1941), Linda Montano (n. 1942), Ana Mendieta (n. 1948), Sophie Calle (n. 1953), Felix González Torres (n. 1957) y Janine Antoni (n. 1964).

[2] Bengoa reconoce a su ex profesor Eduardo Vilches, quien fotografió una plaza pública desde el interior de su casa por un periodo de tiempo como punto de partida conceptual. Comunicación vía email con la autora, 24 de Julio 2004.

[3] La exposición no tuvo lugar debido a restricciones presupuestarias.

[4] A este respecto, recordamos el trabajo reciente del artista guatemalteco Alejandro Paz y los costarricenses Miriam Hsu y Oscar Ruiz-Schmidt cuyas fotografías capturan experiencias familiares, inmediatas en la esfera privada en orden a exponer las convenciones o discursos que proveen multiples lecturas. Ver Jaime Cerón, “The 5th Biennial That Looks to the Caribbean,” / La quinta Bienal que parece ser caribeña, revista ArtNexus 52.3 (2004):91.

Julia P. Herzberg

Doctora en Historia del Arte y Curadora independiente

Mónica Bengoa from Santiago to Venice (Mónica Bengoa de Santiago a Venecia). Herzberg, Julia P. Catálogo obra Bienal de Venecia some aspects of color in general and red and black in particular, p.09-17. Santiago, Chile. 2007

Mónica Bengoa from Santiago to Venice

Among the most enduring themes throughout the twentieth century are the connections between art in life and life in art. Artists continue to reinvent the morphologies, typologies, syntaxes, and visual modes, in seemingly limitless ways that enable the spectator to perceive life’s ordinary people, sights, and objects with fresh vision and new understanding [1]. Mónica Bengoa is a contemporary artist whose exceptional work has made us think anew of the importance of the everyday activity, event, place, and artifact as subject in art. Bengoa privileges people’s routine chores or occupations that might, if not for their artistic presentation or construction, go unnoticed simply because they are so mundane.

Bengoa’s installation Some aspects of color in general and red and black in particular / Algunos aspectos del color en general y del rojo y negro en particular at the 52nd Venice Biennial consists of four large wall murals with 28,000 thistle flowers that re-create the anatomy of insects. Using a macro lens, she magnified the minute details of different insects, which when projected on the walls function like large-scale drawings. The artist then meticulously covers every detail of the insects’ anatomies with the thousands of thistles, leaving their outlines barely visible. The tonal variations within the floral massing –nine reds in two of the images, and nine greys and blacks in the other two– create a sense of depth, texture, and sensorial pleasure, thereby disguising the frightening appearance of the gigantic images of insects one might associate with horror movies.

Bengoa’s work during the previous nine years expands the lessons of minimalism: repetition and the grid; and the artist’s touch, emphasis on handcrafting, the importance of (auto) biographical references. Her large-scale wall installations are a study in counter-expectations. Although ephemeral, their production is labor-intensive. The work is visually elaborate, and, for its duration on the wall, it remains a traditional art object.

In The color of the garden / El color del jardín of 2004, for example, Bengoa took photographs of plants on her windowsills, views of the front lawn from her living room window, areas of her bedroom with its bed and night table, the living room with a sofa, books, fragments of artworks, and doors –open and closed. These images comprise a composite but nonlinear scene of the artist’s interior living space, with a view to the outdoors [2]. Some of the images were installed at Latin Collector Gallery in New York as photographs, and other as large-scale wall murals in which the photographic images were transferred digitally to small paper napkins and then hand-colored, one by one, covering the entire surface. The artist uses hundreds, sometimes thousands, of napkins in which fragments of images, originally captured by the camera, are pieced together to compose the large-scale composition.

Mónica Bengoa conceived of a sequence of wall installations titled Kitchen of 2003-2004, which was to have depicted her performing chores in the kitchen [3]. In the different venues, each ephemeral scene would have been created with approximately 800 hand-colored paper napkins. In Ejercicios para el fortalecimiento del cuerpo / Exercises in strengthening the body of 2002, the photographs, ink-jet printed on watercolor paper, are of the artists performing domestic scenes, and in Resistance Exercises of 2002 the artist depicts common kitchen utensils on thousands of small paper napkins. En Vigilia 4 / Vigil IV (2001-2002), Bengoa photographed her children every day for seven months while they brushed their teeth at the bathroom sink. The 640 photographs from that series reaffirmed the artist’s keen interest in the obsessive repetition of daily rituals as starting points for her art / life dialogue.

Sobrevigilancia / Overvigilance of 2001 is an enlarged image of the artist’s bathroom sink created with 9,160 dry flowers in tones of green to form a wall-size mural. That work is a forerunner in terms of the materials used in the Venice Biennial wall murals. In En Vigilia / Vigil of 1999, an earlier exploration of Vigil IV, is also an extensive series of photographs in which the artist captures her children sleeping every night over a period of five months. At the end of the project, the 310 photographs of them were distinguished one from the other by the small changes noted as they moved in their sleep. Both Vigil IV and Vigil form a kind of topography of daily actions that define her children’s and, by extension, anyone else’s customs at a given time and place [4]. Bengoa’s interest in the repetition of daily rituals not only serves as the starting point of her art/life dialogue. In an odd way, these rituals are not much different from Sophie Calle’s extensive series of photographs of unmade beds shots in a hotel room that, over time, registered the sleeping positions of the unknown hotel clientele. In the conceptual work of Calle, however, the spectator never saw the sleeper’s figure, only the impressions left on the wrinkled sheets. The person’s identity and activities were left to the viewer’s imagination. In contrast, Bengoa’s series were actual biographical documents of her offspring whose presence was fixed for a moment in time, images that might be placed in the family photo album.

Critically, Bengoa’s work compels us to stop momentarily and reconsider our own personal spaces, their configurations, and their meaning in our lives. It also challenges us to redefine the way we use our space, the way our space reflects upon us through the objects we include, arrange, and observe. Some aspects of color in general and red in black in particular is less about the artist’s explorations concerning her private space and its routine aspects as it is about creating a more public space that somewhat dwarfs the spectator, almost to the point of feeling overwhelmed. Bengoa’s materials and processes remain similar, but she has begun to use the camera for different ends. Instead of capturing the prosaic at home in hundreds of sequential shots, she captures a few macro shots of the prosaic outdoors, thereby enlarging our perception of nature.

The following conversation between Julia P. Herzbergh (JPH) and Mónica Bengoa (MB) took place over several months in 2003. It is included here because it provides an understanding of the artist’s processes and concepts for her photo-based installation work.

JPH: Some where in the drumbeat monotony of routine rituals such as sleeping, washing, or grooming, you have perceived a vital pulse (energy, a sign of life). Why were you interested in capturing the repeated moments in your children’s lives?

MB: My work has focused essentially on staging the scenes of everyday life. I have consistently recorded activity and situations in the domestic environment. I have captured my children as objects in these photographs in situations that are not memorable, that do not stand out in a family’s history; rather, they take hold because they are not distinctive but just normal. I believe that domestic routines turn into rituals that sustain our notion of identity. Through repetition, ritualized domestic routines not only become visible but they also establish a time frame. I am interested in focusing on these routines because of their fragile and ephemeral nature. And while routines are fleeting, they also provide structural support in the safe space of “home”.

JPH: More recently, in Resistance Exercises (2002), you seemed to have found a kind of poetry in the depiction of common kitchen objects such as pots, pans, and stoves. What is it that attracts you to the portrayal of common objects in everyday life? Or, for that matter, what attracts you to performing kitchen chores as a subject in your act?

MB: My focus on certain objects from everyday life is mainly based on their unnoticed presence, at least on a conscious level, in our daily round of activities. In recording these kitchen objects, I decided to perform domestic chores of the most routine sort, in an attempt to create a sense of familiarity for the viewer, who can in turn relate to these kind of objects.

In Resistance Exercises: Rubbing and Resistance Exercises: Absorption, I took pictures of old kitchens in modest restaurants in La Vega, a popular market in downtown Santiago. These works were intended to be exhibited in Boston and New York. Therefore I thought I should broaden my notion of domestic objects, from my home to that larger one –the city where I live. In the market I found large family-sized pots, worn-out kitchen utensils, and tiled walls stained with leftovers from previous meals. I was not as interested in recording the formal or functional features of the kitchen utensils as I was in capturing the traces left by constant use.

JPH: You come from a strong background in printmaking. (It was your major as an undergraduate, and now you teach printmaking at the Catholic University.) For the last several years (2001-2003), your work has involved innovative printmaking techniques. Can you describe the processes you will use in Kitchen, a work similar in form to Resistance Exercises: Absorption (2002), a wall mural for which you used 1,330 small paper napkins?

MB: During the last two years I completely changed the methods and materials I use when I transfer photographic images. I did this my interchanging materials with other media and supports, by inverting formal strategies derived from drawing and painting, and by including the use of objects. These methods have allowed me to create an effective transfer device for producing large mural paintings made from common objects from everyday life. The final work keeps the reproductive quality of the original photographic structure. My proximity to printmaking has allowed me to expand its processes and incorporate frottage in my work, among other techniques.

In the series Resistance Exercises, the original images were photographs of popular kitchen utensils that I later retouch digitally to differentiate the diverse chromatic areas. After redrawing every specific color zone, I print the outline on the paper napkins. Trying to be true to the original chromatic referent, I “paint” each napkin with crayons by using a rubbing technique (frottage) over the tablecloth on my dining room table, so that the texture of the surface transfers onto each napkin.

JPH: You have spoken to me about your interest in focusing on the fragile aspects of the daily rituals because you find in them the possibility of building a new “home”. Could you define what you mean by building a new home?

MB: My production process inevitably involves going back and forth, to and from the house. These crossings generate a certain state os suspension that requires me to build a protective shell in order to survive these constant transitions, “to carry a house on my back.” Having learned to survive that constant passage from place to place (from home to museum), I can set up my “studio of the moment” in any new space.

[1] Among the many outstanding artists who have made us think anew of the importance of the ordinary as a defining element of art are first Duchamp, then Warhol (b. 1928), and many of his generation, continuing with the more recent conceptual artists Robert Wilson (b. 1941), Hanne Darboven (b. 1941), Linda Montano (b. 1942), Ana Mendieta (b. 1948), Sophie Calle (b. 1953), Félix González Torres (b. 1957), and Janine Antoni (b. 1964).

[2] Bengoa acknowledges her former art professor, Eduardo Vilches, who photographed a public plaza from his interior window over a period of time as a conceptual point of departure. Email communication with the author, July 24, 2004.

[3] The exhibition did not take place due to funding restrictions.

[4] In this regard, we recall the recent work of the Guatemalan artist Alejandro Paz and the Costa Rican artists Miriam Hsu and Oscar Ruiz-Schmidt whose photography captures immediate familial experiences in the private sphere in order to expose the conventions or discourses that provide multiple readings. See Jaime Cerón, “The 5th Biennial That Looks to the Caribbean”, ArtNexus 52:3 (2004): 91.

Mónica Bengoa from Santiago to Venice. Herzberg, Julia P. In Venice Biennial project catalog, some aspects of color in general and red and black in particular, p.09-17. Santiago, Chile. 2007

Julia P. Herzberg, Ph.D.

Art historian and independent curator