Recorrer el mundo, por tierra y por mar, de uno a otro polo; interrogar a la vida, en todos los climas, en la variedad infinita de sus manifestaciones, he ahí por cierto una oportunidad gloriosa para quien sabe ver; he ahí el magnífico sueño de mis años jóvenes, cuando me deleitaba con Robinson. A las ilusiones rosas, ricas en viajes, pronto sucedieron las realidades desabridas y caseras. Las junglas de la India, las selvas vírgenes de Brasil, las altas cimas de los Andes, que adora el cóndor, se redujeron, como campo de exploración, a un recuadro de guijarros rodeados de cuatro muros. (…) Recorro este claustro una y otra vez, cien veces, en tramos cortos; me detengo aquí y allá; pacientemente, hago preguntas y, de vez en cuando, recibo un jirón de respuesta.

J. Henri Fabre, Souvenirs entomologiques

Contra un fondo en que el azul se alterna con zonas de rojo y de verde, manchadas de puntos dorados dispuestos en grupos de a tres, se alza, del mismo color que el fondo, una trama de ramas que, entrecruzándose en una maraña, recubren entero el espacio cuadrado, con bordes dorados. Cada rama culmina en un grupo de tres hojas (¿o son pétalos?), o en la corona de una flor cuyo cáliz apunta hacia dentro de la superficie pintada. Del mismo color que los bordes del cuadro, ocupando casi toda su extensión, una R mayúscula entreverá sus tres trazos (la recta vertical, la curva y la diagonal descendente que casi se funde con la esquina inferior derecha del cuadrado) con las ramas de la planta. En el espacio que marca el semicírculo de su mitad superior, se ve una escena relativamente realista cuya profundidad contrasta con la condición decorativa, casi de arabesco, del follaje. Ella incluye un árbol paralelo al trazo vertical de la R, cuyas ramas y hojas se extienden hacia el trazo curvo de la misma. Junto al árbol, un camino serpenteante se aleja hacia una montaña y, un poco más lejos que el árbol, dos construcciones que parecen silos se alzan, con paredes blancas y techo cónico color café, no se sabe si de paja, tejas o madera. Posadas sobre esos cilindros se ven las figuras oscuras de una suerte de hormigas con ocho patas y dos pares de largas antenas, además de unos insectos con alas que también se distinguen trepados al tronco del árbol, parecen abejas o avispas. Un grupo de especímenes de un tercer tipo de insecto, tal vez cucarachas, ocupa el espacio cubierto de pasto que queda entre un tronco caído y el azul del fondo, que parece ser un río con respecto a este paisaje. Al exterior del cuadrado dorado que contiene estas imágenes, se alcanza a ver un texto, cuya primera palabra, escrita en mayúsculas dispuestas junto a la esquina superior derecha del cuadrado, es RESTAT (la R es su primera letra, unas quince veces más grande que las otras).

Como es fácil adivinar, no se trata de una de las imágenes que ha elaborado Mónica Bengoa para esta exposición, sino de una página de un manuscrito medieval, cuya reproducción fotográfica contemplo mientras comienzo a escribir este texto, luego de haberla escaneado de un libro de la biblioteca, donde se reproducen las más notables ilustraciones de un edición italiana del siglo 15 de la Historia natural de Plinio el Viejo [1]. La palabra “restat” es una transcripción errada de la primera frase de su libro XI, dedicado a los insectos y a las partes del cuerpo: “Quedan [por tratar todavía] animales de un estudio infinitamente delicado [“Restant inmensae subtilitatis animalia…”], puesto que ciertos autores han sostenido que ellos no respiran y que incluso carecen de sangre.” [2] Plinio explica luego por qué se utiliza el nombre “insecto” (insectum, una palabra creada por él para traducir el griego entomon, de donde viene nuestra “entomología”) para esos animales “sutilísimos”: “han sido denominados de este modo a causa de las incisiones que, en la nuca o en el tórax o el abdomen, dividen en segmentos las diversas partes de su cuerpo, que no están unidas sino por un delgado canal. (…) Nunca aparece tanto como en ellos –continúa Plinio– la habilidad de la naturaleza (naturae rerum artificio).” La palabra misma se refiere a esas incisiones o secciones en el cuerpo de esos diminutos animales, cuyo nombre proviene del verbo secare (cortar, dividir, decidir).

¿Por qué dar este rodeo para comenzar a hablar de este grupo de dibujos de Mónica Bengoa reunidos bajo el título “Entre lo exhaustivo y lo inconcluso”? En parte, porque me parece que esta digresión roza muchos de los temas que su obra abre: la relación entre las palabras y las cosas, por cierto, pero también la relación entre el lenguaje y las imágenes visuales, el tema de la escala de la representación en relación a nuestro cuerpo y a las estructuras en las que se dispone, el problema de la clasificación de los objetos y el del resto que en ellos se resiste a entrar en un sistema, lo que impide clausurar cualquier enciclopedia por completo. Esta ilustración pone además de manifiesto la proximidad entre los trazos con los que se representa a los insectos y los trazos con los que se arma la figura de las letras que hablan de ellos, una inquietante semejanza que a menudo se menciona cuando se habla del origen de la escritura, de la práctica de la caligrafía, o de la simple contemplación de signos impresos en la página [3]. Las figuras de Bengoa me parecen por momentos el esbozo de un alfabeto que no comprendemos, o las ruinas de un lenguaje jeroglífico sin piedra roseta para descifrarlo, las ilustraciones de un tratado cuyo texto se ha perdido, y que por tanto ya no pueden ordenarse en función de relato ni retrato alguno.

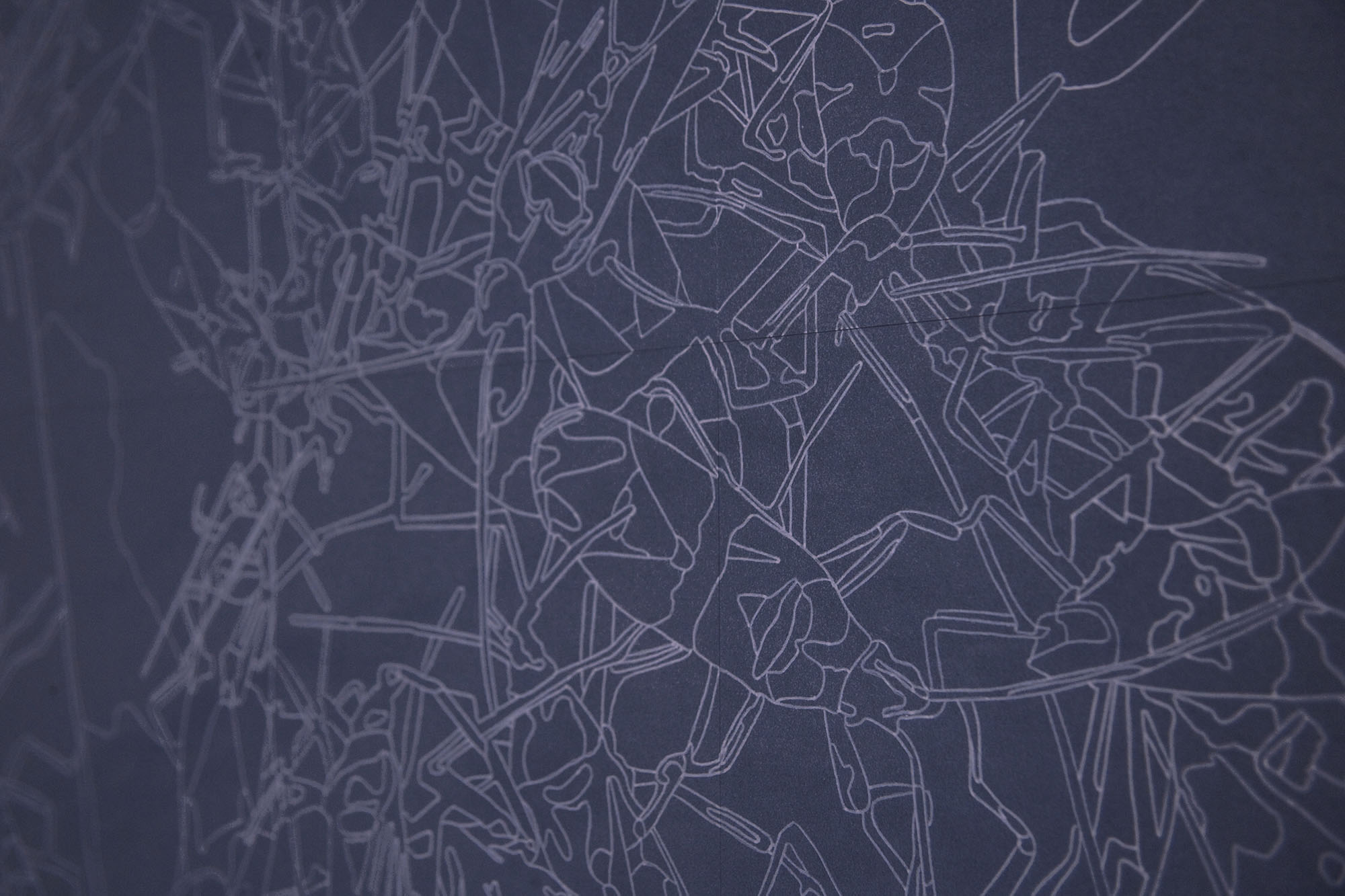

Hay, finalmente, otra razón para empezar con un rodeo: los dibujos de Bengoa se estructuran con frecuencia en ese gesto, el de circunscribir, que es el mismo de una enciclopedia (literalmente algo como educación en círculos, en el sentido de una educación que lo abarca todo): gran parte de sus trazos, impresos o a lápiz, delimitan una zona, un territorio. Tal vez es por eso que estas imágenes, vistas de cerca, tienen algo de cartografías, de mapas, dibujos de un continente que no conocemos y que no se sabe si tiene la escala mundial, desbordante, de la fantasía infantil de Henri Fabre o del claustro estrecho al que lo han confinado sus años maduros. Por una parte, ese circunscribir, definir, decidir, y por otra el traspaso, el pasaje del mundo a la página o pantalla, a una superficie, sabiendo que sus contornos en último término las excederán (como sucede con las figuras que aquí dibuja Bengoa, nunca vistas de cuerpo entero sino fragmentadas o en escorzo). Borges imaginaba un mapa perfecto que coincidiría en su tamaño con el territorio al que equivale: exacerbando ese gesto, podríamos imaginar que Bengoa propone unos mapas que exceden la escala de lo que dibujan, la amplían y explotan (blow-up) hasta casi lo irreconocible.

¿Qué significan la circunscripción, ese gesto envolvente, y la amplificación que la permite? Como escribe Marianne Moore, en un poema que habla del anillo de personas que se forma en torno a un saltamontes de alas tiesas (“We stood like the snake swallowing its tail, comprising a ring”), todo círculo es un símbolo [4]. Pero, tal como el poema de Moore, enigmático en su concisión, los dibujos de Bengoa se resisten a cualquier lectura fácil, a cualquier desciframiento acelerado (como los insectos del jardín de Fabre, que sólo responden muy de vez en cuando a sus preguntas). Pero también se resisten, hay que agregar, a la cerrazón total del ouroboros, la serpiente mordiéndose la cola que simboliza con frecuencia la perfección, pero también el tiempo cíclico, y la autorreflexividad. La obra de Bengoa en su conjunto, de hecho, me parece pertenecer a un momento en el arte local e internacional que, sabiendo bien que toda imagen no es más que un conjunto de líneas o colores sobre un plano (como afirmó famosamente Greenberg a propósito del expresionismo abstracto), retorna sin embargo a la representación de lo real, no tanto con fascinación por el ilusionismo que borra el trazado en favor del referente (mirando qué se pinta o dibuja antes y en lugar de ver que se pinta o dibuja) sino con una obsesión por los procesos mediante los cuales esa transferencia de la tridimensionalidad al plano puede suceder y las diversas modalidades que una forma puede adquirir una vez transpuesta.

En el trabajo de Bengoa, como en el de muchos otros, el dibujo está mediado entonces por la fotografía, que captura lo real con la misma supuesta objetividad de los ojos, pero con una capacidad técnica de la que estos carecen, y que es la que permite la desproporción con la que juegan los dibujos de Bengoa. Esa desproporción, el inmenso tamaño que ella confiere a lo ínfimo (inmensae subtilitatis animalia) tiene no poco en común con la escena de tantas películas en que un insecto se ve convertido en gigante, o un ser humano reducido a dimensiones diminutas. Los antecedentes literarios de esas fantasías, como Los viajes de Gulliver o Micromegas, imaginan esa mutación de escala aproximadamente en el mismo momento en que la ciencia exploraba la posibilidad de servirse de los avances en la fabricación de lentes ópticos para observar lo ínfimo y lo desmesurado, con el microscopio y telescopio. Ya Tesauro había comparado la metáfora al catalejo galileano, en su aproximación de lo distante para generar la meraviglia, pero el siglo XVIII propone una mutación irreversible en que se pasa de la representación a la clasificación, tal como el siglo XVII había pasado de la semejanza a la representación: Linneus comienza sus estudios universitarios el mismo año en que Swift publica los Viajes [5]. Si la fascinación del barroco con las posibilidades de servirse de una imagen proyectada en una cámara oscura como base para el trazado de figuras (una operación no tan lejana de la que ejecuta Bengoa), es, en cierto modo, parte del mismo proceso de investigaciones sobre la naturaleza de la óptica que le permite a Swift imaginar confrontaciones con enanos y gigantes con un grado de detalle no igualado antes, las investigaciones que terminan por fijar la imagen proyectada en una superficie están emparentadas con las aventuras de esa descendiente de Gulliver, Alice, que no sólo cambia de tamaño varias veces en el curso del relato, sino que conversa largo rato con una oruga [6].

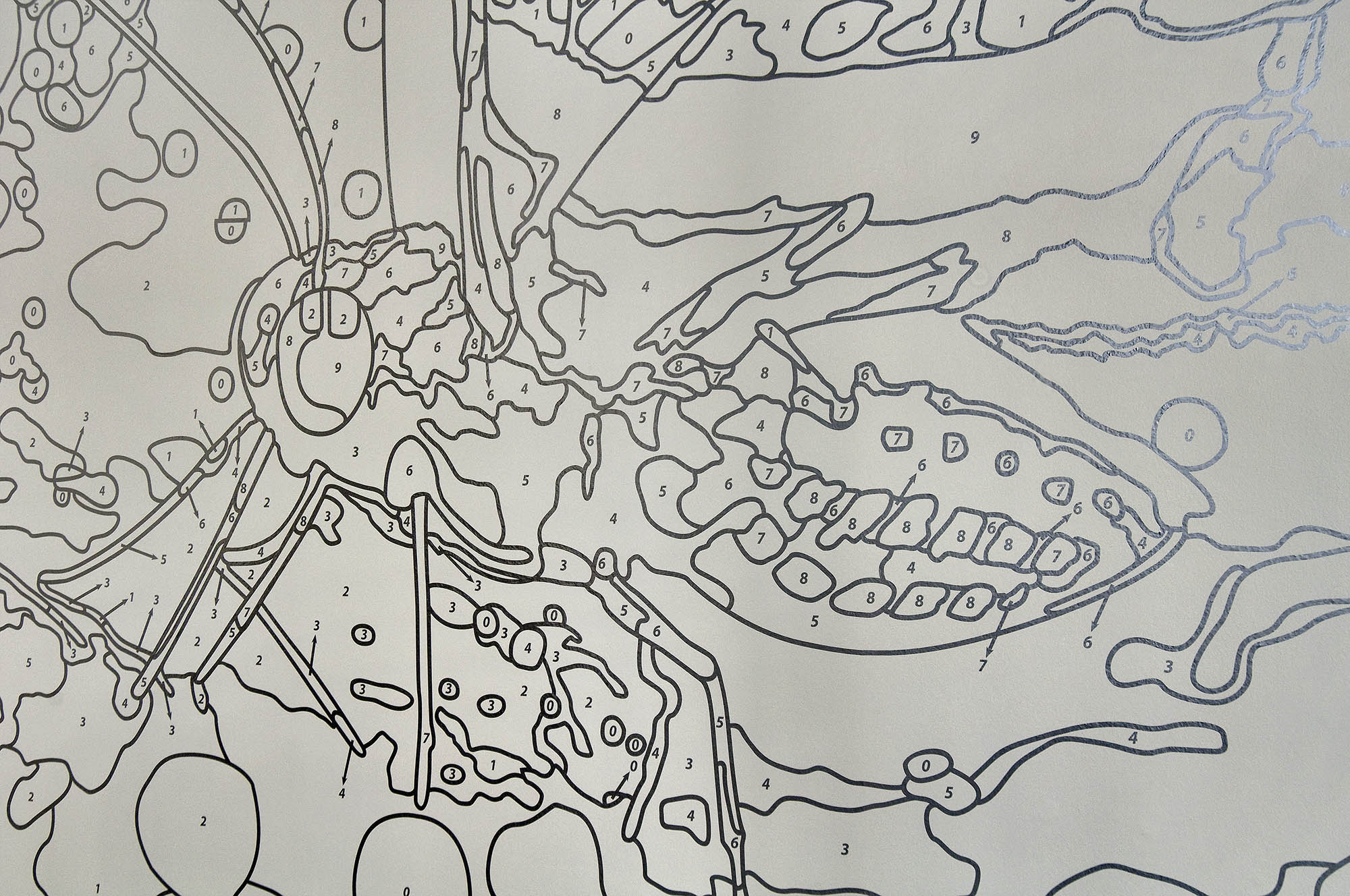

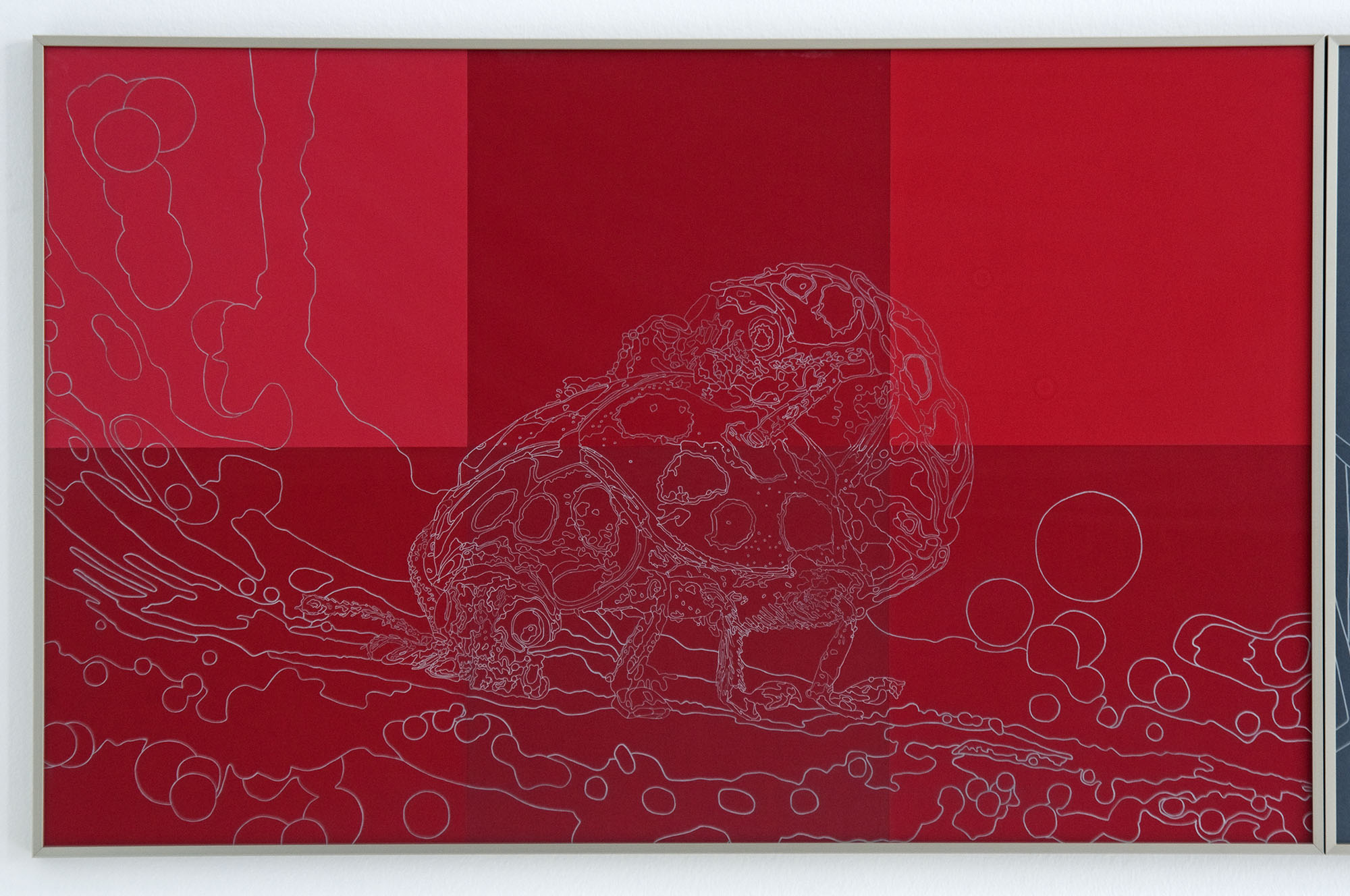

Pero regresemos a Bengoa: hay en sus dibujos otra reticencia que parece distinguirlos de toda su obra previa (y que puede leerse también como un despojamiento, en todos los sentidos): me refiero al abandono del color, que en los trabajos anteriores que conozco aliaba el rigor de la trama con las seducciones del deslumbramiento, el maquillaje de un “engaño colorido” (la frase es de Sor Juana). Aquí no queda del color sino su cifra secreta, el número que lo identifica en una serie que, de nuevo, no tenemos cómo descifrar, un índice de que en este trabajo el proceso se exhibe en estado anterior a lo que era en otras obras la etapa final, se detiene en su estado larvario, rehusándose el lujo de la metamorfosis en mariposa (aunque por otra parte son aquí, en estricto rigor, las manchas de color y no el contorno anatómico lo que se dibuja). Pero toda larva es no sólo un embrión, sino además una máscara (recordemos el motto de Descartes, j’avance masqué, larvatus prodeo): me pregunto en qué medida no es el cuerpo de estos insectos una variante de los sutiles retratos que ha explorado antes Bengoa. Hay en esta obra, entonces, bastante de juego, de acertijo o laberinto, de metamorfosis y disfraz. Pero hay también no poco de melancolía en estas imágenes de insectos atrapadas no en los hilos de una red sino en la trama digital de una pantalla conectada con la red de lo virtual (una versión más sutil del jardín enclaustrado de Fabre), y convertidas en mero dissegno, en idea desnuda, invención sin adorno [7].

La frase de Descartes, que se propone como lema del filósofo (que, enmascarado como precaución contra la censura, desenmascara los falsos saberes), propone también el disfraz como parte necesaria de la teatralidad (“como un actor enmascarado, avanzo en el teatro del mundo” es la frase completa). Se suele ver, sin embargo, en la obra de Descartes precisamente un movimiento intelectual que se aleja de la idea del mundo como escenario, como teatro o como libro que se representa frente a nuestros ojos en un espectáculo inteligible a ojo desnudo para quien comprenda su lenguaje. La misma metáfora del teatro del mundo es la que le sirve como título al tercer volumen de la Historia de las bestias de cuatro patas y serpientes e insectos de Thomas Muffet, impreso póstumamente en 1658 con el título de Theater of Insects or Lesser Living Creatures. Tal como en Plinio (a quien parafrasea con frecuencia), el título de Muffet sugiere la insignificancia de su tema para luego denegarla: less is more, menos es más. Si Plinio había escrito que “nunca aparece más que en los insectos la enorme habilidad de la naturaleza [naturae rerum artificio],” agregando que “la naturaleza no está nunca tan entera como en estos pequeños” [rerum natura nusquam magis quam in minimis tota sit], la introducción al tratado de Muffet agrega que “en los cuerpos grandes el artisanato es fácil, por lo dúctil de la materia, pero en estos que son tan pequeños y desdeñables, y casi nada, ¿de cuánto cuidado?” [8] Lo mismo podría decirse de estos trabajos, que rehusan la grandilocuencia y el adorno, prefiriéndoles la enorme sutileza de lo mínimo, dispuesta ora en ventanas circunscritas con la huella de la trama en que se inscribe su figura, ora en el despliegue más amplio de un soporte adhesivo en el que se inscriben los cortes con los que se traza su cuerpo, disectado en trazos que lo delimitan sin nunca agotarlo.

Pero sería engañarse pensar que los insectos que mira y dibuja Bengoa son los mismos que miraban Plinio o Muffet: por mucho que miremos con cuidado, estos insectos no nos hablan, no responden, no transmiten ni virtudes morales ni secretos simbolismos. A diferencia del escarabajo en el conocido cuento de Poe que al otro, no son claves de un tesoro, ni sus números son cifra de un mensaje que leer. Sería errado, me parece (al menos en un primer momento) intentar arrebatarle a las imágenes que nos propone Mónica Bengoa la máscara para encontrar su rostro verdadero, que está aquí tan en la superficie como en los autorretratos más directos que ella ha ejecutado antes. Estas imágenes son tal vez, en cambio, una invitación a ejercitarse en la semiología de la esfinge de la que habla Agamben en su Estancias, a encontrar, entre lo exhaustivo y lo inconcluso, no la salida al laberinto que proponen estos cuerpos sino la danza de la que provienen y de la que quedan como mudo testimonio.

[1] Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis. Joyce Irene Whalley ed., Londres: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1982.

[2] Traduzco con ayuda de la versión al francés en edición bilingüe de A. Ernout (Pline l’ancien, Histoire naturelle, vol. XI. París: Les Belles Lettres, 1947), de donde saco también el texto latino.

[3] Pienso en los “rayones” ininteligibles de Michaux, que apenas se distinguen de su entomología imaginaria por lo irreconocibles, o en el comentario de Lihn sobre el hormigueo de las letras en la página (“En cambio estamos condenados a escribir, / y a dolernos del ocio que conlleva este paseo de hormigas…”, en “Mester de juglaría”), y ciertamente también en Insectos de Francisco Leal y en el claroscuro de la mosca en el poema de Macarena Urzúa que le sirve de epígrafe a ese libro.

[4] “A ring is the most extreme form / of symbol. Rings mar / The symmetry of loyal regard: we philosophized: / And said we could not have been acts in anyone’s ring, / Had it not been inevitable in the case of this thing.” (“Un anillo es la forma más extrema / de símbolo. Los anillos arruinan / la simetría de la consideración leal: filosofamos: / y dijimos que no habríamos sido actos del anillo de nadie / si no hubiera sido inevitable en el caso de esta cosa).” (“To a Stiff-winged Grasshopper”, The Poems of Marianne Moore, ed. Grace Shulman, NY: Penguin, 2005)

[5] Parafraseo muy aproximadamente aquí la tesis de Foucault en Las palabras y las cosas.

[6] El autor de Alicia en el país de las maravillas no es sólo uno de los pioneros de la fotografía, autor de imágenes que resuenan con algunos de los trabajos anteriores de Bengoa, sino inventor del “Nyctograph,” un dispositivo que permitía tomar notas en las oscuridad y consistía en una carta dividida por una trama de dieciséis cuadrados y un sistema de símbolos para representar el alfabeto.

[7] Podría decirse, en términos tomados del De Pictura de Alberti, que Bengoa se limita en estos trabajos a la circunscripción y composición de figuras, sin figurar la “recepción de la luz”. Los dos primeros componentes del arte pictórico pueden equipararse a la inventio y dispositio retóricas, mientras que el color equivale a la elocutio, el proceso de decoración. Es este último momento el que Bengoa suprime en estos trabajos.

[8] “… in great bodies the workmanship is easie, the matter being ductile; but in these that are so small and despicable, and almost nothing, what care? How great is the effect of it? How unspeakable is the perfection?” (de la introducción de Willy Ley, s/página, Muffet, T. The History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents and Insects. Vol. 3, The Theater of Insects Da Capo Press: New York, 1967).

Fernando Pérez Villalón

Doctor en Literatura comparada, escritor y académico

En catálogo de la exposición individual entre lo exhaustivo y lo inconcluso, Sala Gasco Santiago, Chile. p.8-18. 2009.

The grid and its limits: enormous minuscule maps of an immense subtlety

To travel the world, by land and sea, from pole to pole; to interrogate life, in all climates, in the endless variety of its manifestations, that is certainly a glorious opportunity for those who have eyes to see; that was the magnificent dream of my youthful years, when I delighted in Robinson Crusoe. The rosy fantasies, rich in travels, were soon succeeded by the dull domestic realities. The jungles of India, the virgin rainforests of Brazil, the high Andes peaks, worshipped by the condor, were reduced, as a field for exploration, to a box of pebbles enclosed within four walls. (…) I walk this cloister over and over again, a hundred times, in short stretches; I stop here and there, patiently ask questions, and, every other time, receive a shred of an answer.

J. Henri Fabre, Souvenirs entomologiques

Against a background in which blue alternates with red and green, sprinkled with golden dots arranged in groups of three, a weft of branches of the same background color rise, which, entwining into a tangle, entirely cover the square space with golden rims. Each branch culminates in a group of three leaves (or are they petals?), or in the wreath of a flower with its chalice pointing inwards to the painted surface. Of the same color as the rims of the painting, covering almost all of its extension, a capital R intermingles its three strokes (the vertical line, the curved line, and the descending diagonal, almost blending into the lower right corner of the square) with the branches. Within the space marked by its semicircular upper half, a relatively realistic scene can be seen. Its depth contrasts with the decorative, arabesque-like quality of the foliage. It includes a tree parallel to the vertical line of the R, whose branches and leaves stretch towards its curved line. Next to the tree, a serpentine road sets off toward a mountain, and a little past the tree, two silo-like structures rise, with white walls and a brown conical rooftop (one doesn’t know whether they are made of straw, tiles or wood). Posed on those cylinders, the dark figures of a sort of eight legged ants with two pairs of elongated antennas can be seen, apart from some winged insects also perched on the tree trunk, resembling bees, or wasps. A group of specimens of a third kind, maybe cockroaches, occupies the grass-covered space left between a fallen tree trunk and the background blue, which seems to be a river in relation to this landscape. Outside the golden square containing these images, a text can be made out, with its first word written in capital letters, arranged next to the upper right corner of the square, RESTAT (the r, its first letter, some fifteen times larger than the others).

It is not hard to guess that this is not one of the images produced by Mónica Bengoa for this exhibition, but of a page from a medieval manuscript, at whose photographic reproduction I am looking as I start writing this text, after having scanned it from a library book that reproduces the most notable illustrations of a 15th century Italian edition of Pliny the Elder’s Natural History [1].

The word “restat” is an erroneous transcription of the first sentence of its eleventh volume, devoted to insects and body parts: “Animals of an infinitely delicate study are still (to be treated) –“Restant inmensae subtilitatis animalia…”– since certain authors have maintained that these animals do not breathe, and even lack of blood.” [2] Pliny then explains why the name “insect” is used (insectum is his translation of the Greek entomon, hence “entomology”) for those “utterly subtle” animals: “they have been denominated this way due to the incisions that, on the neck, thorax or abdomen, divide their body parts into segments which are joined but by a narrow channel. (…) With no other animal –Pliny proceeds– does nature’s resourcefulness (naturae rerum artificio) stand out as much.” The word itself refers to those incisions or sections in the bodies of these minuscule animals, whose name originates from the verb secare (to cut, split, decide).

Why take this detour to start referring to this group of drawings by Mónica Bengoa, brought together as “Between Exhaustiveness and Incompleteness”? Partly, because it seems to me that this digression tangentially touches many of the problems proposed by her work: the relation between words and things, certainly, but also between language and visual images, the scale of representation in relation to our body and the structures on which it is displayed, the problem of the classification of objects, and the remains that resist entering a system, preventing the definitive closure of any encyclopedia. This illustration also manifests the proximity between the strokes with which insects are represented, and the ones with which the bodies of the letters speaking of them are assembled, an uncanny resemblance often mentioned when speaking of the origin of writing, the practice of calligraphy, or the simple contemplation of printed signs on a page [3]. Bengoa’s figures at times seem to me like the sketch of a to us incomprehensible alphabet, or the ruins of a hieroglyphic language without a Rosetta stone to decipher it, the illustrations of a treaty whose text has been lost, and which therefore cannot be organized according to any plot or portrait.

Finally, there is another reason to start off with a detour: Bengoa’s drawings frequently structure themselves in that gesture, of circumscribing, the same as an encyclopedia (literally, something like a circular education, in the sense of spanning everything): a great part of her strokes, printed or pencil drawn, delimit a zone, a territory. Maybe this is why these images, seen from up-close, have an element of cartography, of maps, drawings of an unknown continent, whose size we cannot know (it may have the boundless world scale of Henri Fabre’s infantile fantasy, or of the narrow cloister to which he has been confined to in his advanced age). On one hand, that circumscribing, defining, deciding, and on the other, the transference, the transit from the world to the page or screen, to a surface, knowing that its outlines will ultimately exceed it (as with the figures Bengoa draws here, never seen full-length, but fragmented and foreshortened). Borges imagined a perfect map whose size would coincide with that of the territory it equaled to: exacerbating that gesture, we could imagine Bengoa proposing maps that far exceed the scale of what they draw, amplifying and blowing it up to the point when it becomes almost unrecognizable.

III. The microscopic gaze

In one of the meetings we had to speak about her retrospective exhibition, when I asked her for details on the distribution of the works in the museum space, Mónica took me to her workshop, where she pointed at a scale model of the museum in which she had displayed small size reproductions of the works in a tentative order. This is, certainly, a common practice for artists who want to imagine how the works will look like positioned specifically and make sure to find the optimal way to arrange them. But in this case the gesture takes on a special charge due to the role scale transformation procedures have in her work. I looked at the scale model for some time, imaginarily circulating through the museum halls reduced to the scale of a toy.

All work of art, Lévi-Strauss proposes in The Savage Mind, is a reduced model of reality (even works of a monumental or natural size, “since graphic or visual transposition always supposes renouncing to determined dimensions of the object”[7]), a miniature destined to grant us an illusion of power over things by means of an object homologous to them, in an operation located in between mythical and scientific thought. There is some of this in Bengoa’s work, which transposes restricted aspects of reality with a rigor that has a lot in common with obsession, due to its extreme meticulousness, but also with games, due to the gratuitousness of the challenge in each work she sets out to make, without any other goal than the pleasure of exploring what happens, and with the certainty that said self imposed difficulty (that which the members of the Oulipo group called constrained writings, limited, faced with impediments) will show us new ways of looking.

Now, it is not trivial that Bengoa’s changes of scale tend toward the production of images in which the object is extremely magnified, such as her images of insects, her enormous greenish sink reproduced with thistles or her felt murals amplifying book pages until turning them into broad geographies in which the spectator feels he or she could get lost in. If maps and scale models normally have in order to control or conquer it, the microscopic gaze, also eager of knowledge, rather tends toward the vertigo of what is endless, to the detail invading all of our visual field and which we feel we could always increase in size, indefinitely, therefore making us feel minuscule, defenseless, vulnerable. The infinite of outer space, as Pascal knew, may be less terrifying than the infinite of what is negligible, of what is minuscule as a miniature universe in which we can get lost in, and which makes our certainty about us being the measure of all thing stagger.

What do the circumspection, that involving gesture, and the amplification that makes it possible mean? As Marianne Moore writes in a poem about the circle of people that forms around a stiff-winged grasshopper (“We stood like the snake swallowing its tail, comprising a ring”), every circle is a symbol [4]. But like Moore’s poem, enigmatic in its conciseness, Bengoa’s drawings resist any easy reading, any swift deciphering (like Fabre’s garden insects, which only very occasionally answer his questions). But they also resist the complete enclosure of the ouroboros, the snake biting its own tail, frequently symbolizing perfection, but also cyclical time and self-reflection. Bengoa’s work as a whole, in fact, seems to belong to a moment in local and international art that, knowing full well that any image is nothing but a group of lines or colors on a plane (as Greenberg famously stated, referring to abstract expressionism), nonetheless returns to the representation of what is real, not so much with a fascination for the illusionism erasing the lines in favor of the referent (looking at that which is painted or drawn beforehand, and instead of seeing that it is painted or drawn), but rather obsessively examining the processes through which that transference of three-dimensionality to the plane can occur and the many modalities a form can acquire once transposed.

In Bengoa’s work, as is the case with many others, drawing is mediated by photography, a medium that captures what is real with the same supposed objectivity of the eyes, but with a technical capacity which far exceeds theirs, and which allows for the disproportion Bengoa’s drawings play with. This disproportion, the immense size she confers to what is minuscule (inmensae subtilitatis animalia) has not little in common with the scenes of so many movies in which an insect turns into a giant monster, or a human being is reduced to minuscule dimensions. The literary antecedents of those fantasies, such as Gulliver’s Travels or Micromegas, imagine this mutation of scale approximately in the same period in which science was exploring the possibility of benefiting from the advances in the manufacture of optical lenses to observe minuscule and immense objects, by means of the microscope and the telescope. Emanuele Tesauro had already compared metaphors to the Galilean telescope, in its approximation of what is distant to generate the meraviglia, but the 18th century proposes an irreversible mutation going from representation to classification, like the 17th century had gone from resemblance to representation: Linneus begins his university studies the same year in which Swift publishes the Travels [5]. If the fascination of the Baroque period with the possibilities of using an image projected in a camera obscura for the tracing of figures (an operation not that far removed from the one Bengoa executes), is, in a way, part of the same enquiry on the nature of optics that allows Swift to imagine confrontations with Lilliputians and giants with an unprecedented level of detail, the research that ends up fixing the projected image to a surface is related with the adventures of that descendant of Gulliver, Alice, who not only changes size during the narration, but also holds a lengthy conversation with a caterpillar [6].

But let us return to Bengoa: there is another reticence in her drawings that seems to distinguish them from all of her previous work (and which can also be read as a process of reduction to the essentials): I am referring to the abandonment of color, which, in the earlier works I know, combined the rigor of the grid with the seductions of amazement, the makeup of a “colorful deceit” (to quote Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz). Nothing remains of color here but its secret cipher, the number identifying it in a series that, again, we have no way of deciphering. This indicates the extent to which in this work the process is shown in a state previous to what in other works was the final stage. This work remains in a larval stage, depriving itself of the luxury of the metamorphosis into a butterfly (even though, on the other hand, what is outlined are areas of color and not anatomical outlines). But a larva is not only an embryo, but also a mask (let us remember Descartes’ motto, j’avance masqué, larvatus prodeo): I wonder to what extent the bodies of these insects are not a variation of the subtle portraits Bengoa has explored earlier. There is then a strong element of play, riddle or labyrinth, of metamorphosis and disguise in this work. But there is also a considerable amount of melancholy in these images of insects trapped, not in the mesh of a net, but in the digital grid of a screen connected to the virtual web (a subtler version of Fabre’s closed garden), turned into mere dissegno, into a naked idea, an undecorated invention [7].

Descartes’ sentence, proposed as a slogan for the philosopher (who, disguised, as a precaution against censorship, unmasks false knowledge), also proposes the disguise as a necessary component of his own theatricality (“like a masked actor, I advance in the theater of the world” the complete sentence reads), even though Descartes’ work is usually regarded as part of an intellectual movement away from the idea of the world as a stage, as theater, or as a book being represented before our eyes, a spectacle intelligible to the naked eye for whoever understands its language. The same metaphor of the theater of the world is the one serving as title to the third volume of the History of Four Footed Beasts and Serpents and Insects by Thomas Muffet, posthumously printed in 1658 as Theater of Insects or Lesser Living Creatures. Like with Pliny (who he often paraphrases), Muffet’s title suggests the insignificance of his topic to later negate it: less is more. If Pliny had written that “with no other animal but insects does nature’s enormous resourcefulness stands out as much (naturae rerum artificio)”, adding that “nature is never as whole as in these little creatures (rerum natura nusquam magis quam in minimis tota sit), the introduction to Muffet’s treaty adds that “for in great bodies the workmanship is easie, the matter being ductile; but in these that are so small and despicable, and almost nothing, what care?” [8] The same could be said of these works, refusing grandiloquence and ornament, preferring the immense subtlety of these minimal animals, displayed either in windows marked with the trace of the grid within which its figures are inscribed, or in the wider display of an adhesive support on which the traits of their bodies are traced as cuts, dissected in delimiting strokes that can never exhaust them.

But it would be self-deceiving to think that the insects Bengoa watches and draws are the same ones Pliny or Muffet observed: as much as we carefully look, these insects do not speak to us, they do not respond, they transmit neither moral virtues nor secret symbolisms. As opposed to the Gold-bug in Poe’s renowned story, they are not clues to a treasure, or their numbers the cipher of a message to be understood. It would be wrong (at least at this point) to try to strip Bengoa’s images of their mask in order to reveal their real face, which is here as much on the surface as in the overt self-portraits she has previously produced. These images are perhaps rather an invitation to exercise the semiotics of the sphinx Agamben speaks of in his Stanzas, to find, between exhaustiveness and incompleteness, not the exit of the labyrinth these bodies generate, but the dance in which their lines originate and of which they remain as a mute testimony.

[1] Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis. Joyce Whalley publishers, London, Victoria and Albert Museum, 1982.

[2] I translate assisted by the bilingual version into French by A. Ernout (Pline l’ancien, Historie naturelle, vol. 11, Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1947), from where I also took the text in Latin.

[3] I am thinking of Michaux’s unintelligible “scrawls,” barely distinguishable from his imaginary entomology by their unrecognizable nature, or of Enrique Lihn’s comment on the ant-like look of the letters in a page (“We, in contrast, are condemned to writing / and to suffer the sloth of this crawling of ants implies…” in “Art of Jugglery”), and certainly also of Francisco Leal’s Insects, and the chiaroscuro of the fly in the poem by Macarena Urzúa serving as epigraph to that book.

[4] “A ring is the most extreme form/of symbol/rings mar/the symmetry of loyal regard: we philosophized/and said we could not have been events in anyone’s ring/had it not been inevitable in the case of this thing.” (To a Stiff-winged Grasshopper, The poems of Marianne Moore, Grace Shulman publishers, NY, Penguin Books, 2005)

[5] I very approximately paraphrase Foucault’s thesis in The Order of Things.

[6] The author of Alice in Wonderland is not only one of the pioneers of photography, author of images resonating with some of Bengoa’s earlier works, but also inventor of the “Nyctograph”, a device that allowed taking notes in the dark, consisting of a letter divided by a weft of sixteen squares and a system of symbols to represent the alphabet.

[7] It could be said, in terms taken from Alberti’s De Pictura, that Bengoa limits herself to the circumscription and composition of figures in these works, without the “reception of light”. The first two components of pictorial art can equal themselves to the rhetoric inventio y dispositio, while color equals the elocutio, the process of ornatus, decoration. It is that later moment Bengoa suppresses in these works.

[8] From the introduction by Willy Ley, Muffet, T., The History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents and Insects, vol. 3, The Theater of Insects (Da Capo Press, NY, 1967).

The grid and it’s limits: enormous minuscule maps of an immense subtlety. Fernando Pérez Villalón, in Solo exhibition catalogue between the exhaustive and the inconclusive. p.37-39. Santiago, Chile. 2009