Desde muy temprano Mónica Bengoa ha abocado su trabajo al estudio de la fotografía. Incluso antes de egresar de la Escuela de Arte de la Universidad Católica, la imagen fotográfica tomaba un lugar medular en sus propuestas y reflexiones artísticas. Aunque estas investigaciones han incluido una diversidad de preguntas, métodos y propuestas visuales –tal como puede observarse en las obras que componen esta retrospectiva– ha sido un aspecto particular el que ha “comandado” sus pesquisas y sobre el cual la artista ha vuelto de manera recurrente en buena parte de su producción, esto es, la intransitividad de la imagen fotográfica. Dicha “intransitividad” se refiere principalmente a la superación de aquella mirada que frente a una foto se dirige a saciar el deseo de “inmediatez” –en palabras de Bolter y Grusin (2000)–, buscando el reconocimiento del referente, de los objetos y figuras allí representados –el “studium” barthesiano– y obviando su carácter mediado[1].

En sus indagaciones tempranas, Bengoa reflexionó en torno al problema de la “intransitividad” buscando en la propia imagen fotográfica aquello que pusiera a la “vista” la condición significante del medio, sin por ello suprimir el motivo o el componente referencial. Esto puede observarse, por ejemplo, en 203 fotografías (1998), donde los propios elementos representados (segmentos, pliegues y marcas corporales) aluden a texturas, formas, tonalidades, encuadres que invitan a observar y pensar la fotografía como forma de representación –y no como mera huella– de la realidad. Por su parte, en la obra en vigilia (1999), la proliferación de fotos reiteradamente similares gatilla el olvido del tema u objeto de la imagen (cotidiano, familiar, recurrente) a favor de las observaciones sobre la variación cromática y tonal, los cambios casi imperceptibles en los ángulos de captura, los diferentes escorzos y formas que allí comparecen. Estos ejercicios también pensaron los formatos y la disposición espacial de la fotografía, su montaje, yuxtaposición y expansión fuera del límite de la sala (en el caso de Tríptico en Santiago, 2000) como métodos para la investigación del medio. Asimismo, en los trabajos de Bengoa la fotografía escudriñó sus propios límites al ponerse en tensión –sin combinarse– con otros medios como la pintura, el dibujo y el grabado, y también con cuestiones relativas a la forma en volumen.

Esto último resulta gravitante en los ejercicios visuales que Bengoa efectuará durante buena parte de la década siguiente; en ellos la artista ensayará transcripciones manuales de fotografías a soportes no tradicionales, compuestos por materiales tan diversos como prosaicos: cardos teñidos, servilletas de papel, hilos de colores y paños/retazos de fieltro. Es quizás en estos ejercicios de traspaso, en los tránsitos mediales y materiales de la imagen iniciados el año 2001 con Sobrevigilancia, que lo intransitivo de la fotografía se pondera y visualiza de manera más clara y, tal vez, sofisticada.

I

Durante buena parte de los 90, Mónica Bengoa trabajó con fotografías que aludían a vistas o partes del cuerpo, algunos alusivos a su propia imagen, ya fueran singulares retratos que mostraban a la artista disfrazada o adoptando una apariencia masculina, o capturas de algún fragmento corporal en particular. Como resultado de aquello, se produjo una sistemática acumulación de fotos descartadas, remanentes que jamás se exhibieron. No obstante, estos “despuntes” fueron recuperados y reunidos hacia finales de la década en 203 fotografías, conformando una suerte de pequeño “atlas” de lo corporal. Este conjunto incluía imágenes de diversa índole ofreciendo vistas parciales y segmentadas sobre el cuerpo.

Aunque a una escala bastante más modesta, algo del procedimiento utilizado en 203 fotografías recuerda el macro proyecto Atlas de Gerhard Richter[2]: la valoración de las imágenes descartadas, su clasificación por temas, su yuxtaposición variable, entre otros. Como ha señalado Benjamin Buchloh en su iluminador texto acerca de la obra del alemán (1999), la noción de “atlas” fue apropiada por el arte del siglo XX –y por la historia del arte desde Warburg– utilizándose de modo más “metafórico”[3], contraviniendo incluso su acepción decimonónica que lo entendía como una forma comprensiva y abarcadora de sistematización del conocimiento en todas las áreas de las ciencias empíricas. Más allá de la escala de los proyectos y de sus intenciones, interesa relevar el gesto que moviliza la producción de estas obras, donde el acceso a la imagen no acontece de manera aislada, sino en un entramado más complejo que la sitúa y significa. Esta red no pretende, sin embargo, ser totalizadora ni “holística”, sino más bien parece insistir en su carácter fragmentario, parcial y arbitrario. Y aunque la voluntad taxonómica resulta innegable, las acumulaciones y yuxtaposiciones de fotografías permiten una visualización pluricentral, donde no existe un sistema único ni lógico de recorrido y observación.

De este modo, la obra de Bengoa gatilla distintas asociaciones entre las imágenes que la componen, desde vistas más generales –medio cuerpo o cuerpo completo– a acercamientos o primerísimos planos de cicatrices, cavidades y pliegues en los que cuesta trabajo determinar qué parte del cuerpo está allí representada. Asimismo, el espectador se encuentra con imágenes a foco y otras algo más borrosas ya que, como bien advirtió Ricardo Cuadros (1998) la primera vez que la obra se montó, en este repertorio pueden distinguirse diferentes tiempos (velocidades) de obturación[4]. Igualmente comparecen distintas texturas y formas que van rimando entre ellas pero también “desentonando”. Es así como en ciertos sectores del conjunto se pondera lo lineal, generándose un particular ritmo entre imágenes que aluden, tanto a un pliegue o una cicatriz como a la unión de los labios o los párpados. Lo anterior contrasta con un grupo de fotografías donde, en lugar de lo lineal, es el sombreado o las mediatintas lo que captura la mirada.

Resulta interesante, además, mirar este repertorio no solo como un ensayo sobre una imagen posible de lo corporal, sino también como un estudio sobre el cuerpo como soporte de inscripción. En ese sentido, se produce un espejeo entre el motivo de la instalación y la fotografía en su arista más “indicial”, que polemiza de cierta forma con lo que se ha planteado en relación a una mirada intransitiva sobre la imagen fotográfica.

II

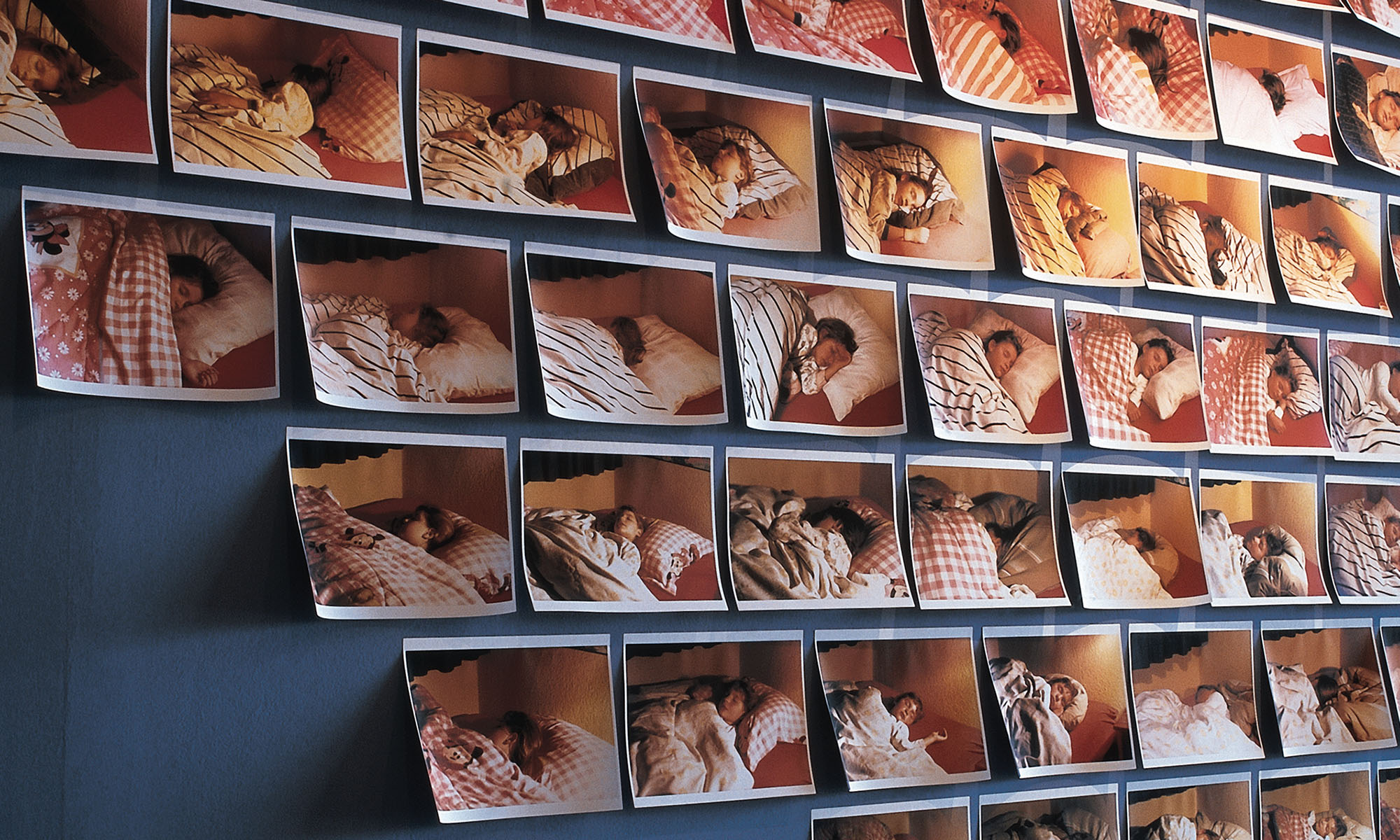

Y aunque 203 fotografías presenta una complejidad para el espectador, puesto que el punto de vista puede variar continuamente, poniendo en entredicho cualquier “sintaxis” preestablecida, en las fotografías mismas no existe una aspiración autoral, es decir, no hay inscrita una intención “artística”, son más bien fotos amateur, caseras. Lo mismo ocurre con las imágenes que componen en vigilia, el primer proyecto de una serie en que Bengoa fotografía de forma sistemática a sus hijos desarrollando actividades insignificantes y rutinarias: cepillándose los dientes, almorzando o, en este caso, durmiendo.

Susan Sontag escribió que uno de los primeros y principales usos populares de la fotografía en el siglo XX fue el registro de acontecimientos familiares memorables: casamientos, cumpleaños, vacaciones, etc. Así, fotografiar momentos en familia –especialmente si había niños/as– se convirtió en una especie de ritual social, cuyo objetivo era conmemorar y restablecer simbólicamente los lazos entre los miembros del clan[5]. Por el contrario, en las imágenes de Bengoa no ocurre nada excepcional. Lo que se capta, en cambio, son esos “espacios en blanco”, sin sobresaltos, pero que, sin embargo, resultan absolutamente necesarios para producir el contraste entre lo ordinario y lo memorable. Podría pensarse, entonces, que lo que en en vigilia se ve representado es ese dilatado y homogéneo lapso de tiempo en que los sucesos que acaecen son superados y descartados de forma casi inmediata: es el tiempo “profano” que se ubica entre los momentos de uso y práctica de la fotografía como ritual familiar. Se introduce así una paradoja, o quizás una inversión de los términos, ya que la fotografía reservada para la ceremonia se “desacraliza” por el empleo rutinario y hasta obsesivo del aparato técnico.

Esta repetición “hasta el cansancio” del mismo motivo (310 imágenes en total y presumiblemente otras tantas descartadas), gatilla justamente la pregunta por el procedimiento y la ejecución de la obra: una madre en vigilia, que noche tras noche –sin excepción– captura el reposo de sus hijos. En las imágenes puede verse representado el paso del tiempo, la vigilia marcada por los ciclos estacionales, percibiéndose tanto los cambios más evidentes (en el color y diseño de las sábanas) como los menos notorios (el largo o la forma del pelo de los niños). Este tema del cuerpo exigido en el proceso de producción se verá intensificado –y llevado al límite– en proyectos de mayor envergadura que la artista desarrollará en la década siguiente como Sobrevigilancia (2001), enero, 7:25 (2004) o su serie ejercicios de resistencia (2002), por poner sólo algunos ejemplos. De la misma manera, y aunque las instalaciones fotográficas arriba comentadas abarcaban una superficie bastante significativa, la imagen ampliada a escala mural se tornará recurrente en el trabajo de Bengoa a partir del año 2000. Es específicamente en Tríptico en Santiago (2000) donde se constata este cambio de formato, allí el tratamiento de lo privado y lo íntimo, que ya se visualizaba en las propuestas anteriores en relación a lo corporal y a lo familiar, alcanzará dimensiones considerables e implicará su emplazamiento en el espacio público.

III

Tríptico en Santiago se compone de tres fotografías en las que se aprecia a los hijos de la artista ejecutando la misma acción (comiendo), en el mismo lugar (la cocina), en distintos tiempos. Las imágenes se instalaron en una valla publicitaria de tres caras ubicada en la intersección de las calles Bellavista y Loreto. Gracias a los prismas triangulares comandados mecánicamente, era posible la rotación repetida y regular de las diferentes fotografías, produciéndose, de ese modo, un singular tríptico cuyos módulos jamás se percibían al unísono.

La apropiación artística de los espacios publicitarios urbanos había sido ensayada por artistas contemporáneos años antes, siendo un caso emblemático el del cubano Félix González Torres y su Billboard of Bed (1992)[6]. Aunque con intenciones y propuestas conceptuales y visuales bien distintas, en ambas obras se replica el efecto de extrañeza frente a una imagen cuya función es transmitir un mensaje de forma inmediata, pero que por el contrario, resulta confusa e indescifrable. El extrañamiento se produce porque la fotografía se comporta de manera ambigua: por su aspecto y “contenido” podría perfectamente cumplir con el objetivo de promocionar un producto, pero su “mutismo” desconcierta. En ese sentido, son imágenes que simultáneamente se ubican en y fuera de contexto, que operan bajo las lógicas visuales del anuncio publicitario pero que al mismo tiempo se desmarcan, resultando ineficaces.

En Tríptico en Santiago, la foto casera, sin esplendor y la escena privada e intrascendente entra en tensión con la máxima visibilidad y centralidad del espacio (público) de emplazamiento. Esta interesante divergencia será explorada por Bengoa en varios de sus proyectos de traspaso manual de imágenes fotográficas a materiales/soportes no tradicionales. Como ya se ha dicho, el primer ejercicio donde la artista pone a prueba un procedimiento de transcripción es en Sobrevigilancia, instalación de la cual sólo existen registros visuales y alguno que otro “vestigio” material[7].

En esta obra convergen, además, dos inquietudes que rondaban a la artista desde hace algunos años. Por una parte, y como se ha visto, las indagaciones en torno a la intransitividad de la imagen fotográfica y por otra, las exploraciones materiales que ya se observaban en Cantidad y recurrencia: los vientos (2000) y en En suspensión (2001), dos murales de muy distinta índole que Bengoa compuso a partir de flores naturales (cardos y siemprevivas).

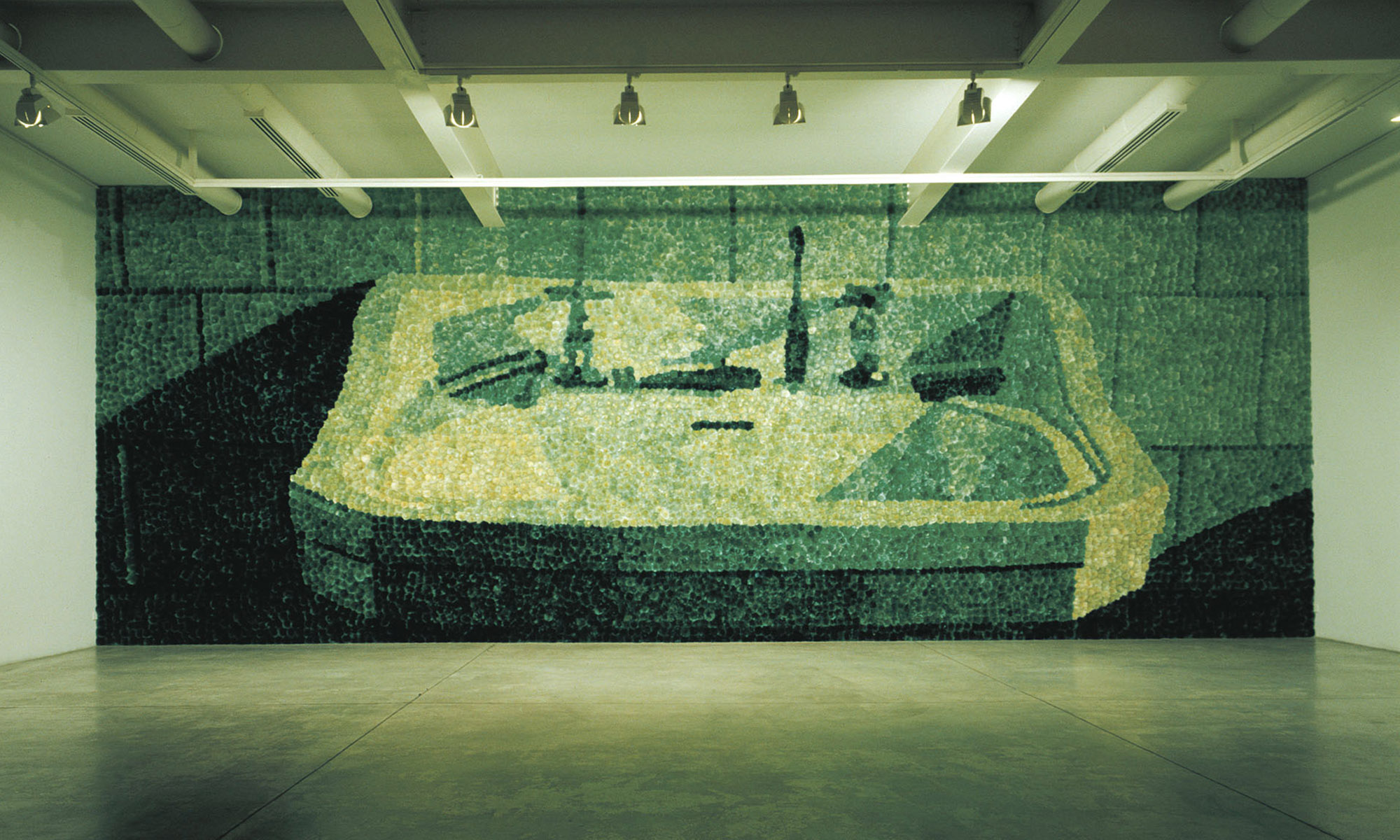

En este proceso de investigación artística, Sobrevigilancia pone nuevamente de relieve el tema de la mirada “vigilante”, la cual –como recuerda Sontag– se vio intensificada con el advenimiento del aparato fotográfico en el siglo XIX y su instrumentalización para el ejercicio del control social[8]. No obstante, la mirada atenta y celadora que se filtra en la imagen de Bengoa se vuelca sobre lo nimio e insignificante, provocando un “dispendio” del recurso técnico. En el mural se ve representado el lavamanos de un baño común y corriente, en el que se alcanzan a reconocer dos pequeñas escobillas de dientes, el dentífrico y un jabón. La pregunta, entonces, es a qué se dirige esa mirada vigilante o con qué objeto se emplea realmente.

Sin duda, es el proceso de transferencia de la fotografía lo que demanda una atención visual intensa, prolija y metódica. Si bien la artista se ha servido de programas computacionales para descomponer la imagen modelo (que nunca está a la vista del espectador), elaborando plantillas donde se delimitan las diferentes zonas de color que conforman la representación, la ejecución del traspaso se realiza en buena medida “al ojo”. El procedimiento se hace aún más complejo si se considera que la traducción de la fotografía se efectúa a un soporte confeccionado con flores de cardo teñidas, es decir, a algo que tradicionalmente no se conoce como un medio de la imagen. Territorio desconocido donde se exploran a la vez que se ponen a prueba las posibilidades técnicas y visuales del material en que la imagen se re-corporiza.

De este modo, se desprende la pregunta ¿a qué medio se traspasa la foto?, ¿a un “pre-medio”, a un nuevo medio arcaico? Si Sobrevigilancia se pone en perspectiva y se observa en relación a ciertos murales donde Bengoa utiliza otro tipo de materiales y procedimientos para efectuar la transferencia de fotografías (servilletas coloreadas a mano, puntadas de hilo, fieltro calado), podría decirse que en cada proceso comparecen distintas medialidades: pintura, grabado y dibujo. Cada mural se nutre, entonces, de diferentes aspectos y características de los medios tradicionales (color, línea, textura, mediotono), sin adscribir a ninguno de ellos en específico. Así, la artista a través del uso de materiales domésticos ha buscado simular la conjunción de medios manuales para simular, a su vez, el medio técnico.

En estos ejercicios de traspaso, la intermedialidad, tal como la entiende Hans Belting (2007), es decir, las mutuas influencias (rivalidades y diálogos) entre los distintos medios de la imagen, se plantea como una manera de estudiar sus características y especificidades[9]. En el caso de Sobrevigilancia, la fotografía, sobre la que comúnmente se ha vertido la idea de transparencia o neutralidad significante, “desoculta” su condición mediada al tornarse, entre otras cosas, más pictórica. De este modo, el cardo como mancha (unidad de color irregular) vuelve menos nítidos los contornos de los objetos representados, haciendo difícil distinguir aquellos elementos que se supone están “a foco” en la imagen. Así, en la obra de Bengoa la inmediatez impuesta al medio fotográfico igualmente se satisface: los objetos referenciales son identificables, sin embargo, su “pictorialización” simulada, que por ejemplo convierte a la escobilla de dientes en una mancha verde abstracta y en volumen, hace simultáneamente reconocible al medio, a los medios en ella implicados.

Pero la observación del mural no sólo comporta una exigencia visual para el espectador, la mirada también se ve cautivada por el sensualismo de la imagen. Pese a la austeridad de la paleta cromática, las dimensiones de la obra (9.160 cardos que abarcaban un total de casi 54 m2), la textura y el suave relieve que aportan las flores secas teñidas, tientan, provocan al tacto; impulso o reacción que forcejea con la automoderación gatillada por el peso de la mirada (del) vigilante. En adelante, los trabajos de Mónica Bengoa sabrán compensar, cada vez con mayor maestría, el estudio acucioso del medio fotográfico con el deleite sensorial frente a la imagen, el cual, a través de la mirada, activa recepciones que desbordan y amplían lo meramente visual para abarcar una escala corporal.

Referencias

[1] Bolter, Jay David y Grusin, Richard. “Inmediatez, hipermediación, remediación”, en: Remediation: Understanding New Media, Eva Alvarado (trad.), Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2000.

[2] Proyecto work in progress iniciado en 1962 (y aún vigente), en que el artista selecciona, clasifica y ordena en series una enorme diversidad de imágenes fotográficas producidas por él mismo, donadas o extraídas de medios impresos. Las más de 5.000 fotografías están organizadas en paneles, unidades desmontables que se van disponiendo a muro para componer el Atlas.

[3] Buchloh, Benjamin. “Gerard Richter’s Atlas: The Anomic Archive”. October, vol. 88, Cambridge: The MIT Press, p, 122.

[4] Cuadros, Ricardo. “Escenas de recuperación”, en: Exposiciones 1998, Santiago de Chile: Galería Posada del Corregidor, 1998, pp. 74-76.

[5] Sontag, Susan. Sobre la fotografía. México DF: Alfaguara, 2006, pp. 22-23.

[6] González-Torres instaló en seis vallas publicitarias distintas de la ciudad de Nueva York la misma fotografía monocroma de una cama vacía, desecha, cuyas almohadas aún retenían las siluetas de las cabezas que allí habían reposado.

[7] Los cardos teñidos que componían Sobrevigilancia fueron reutilizados más tarde en Persistencia y variación (2004).

[8] Sontag, op. cit., pp. 19-20.

[9] Belting, Hans. Antropología de la Imagen, Buenos Aires: Kratz Editores, 2007, p.63.

María José Delpiano

Doctora en Estudios Americanos, Magíster en Artes Mención Teoría e Historia del Arte, Licenciada en Estética

Publicado en m. [una tentativa de inventario exhaustivo, aunque siempre inconcluso], Santiago, Chile. Ediciones EUONIA, p. 16-27. 2017.

Intransitivity in the photographic image in the early work of Mónica Bengoa

From very early on Mónica Bengoa has focused her work on the study of photography. Even before graduating from the Universidad Católica Art School, the photographic image took on a central position in her artistic proposals and reflections. Even if this research has included a diversity of questions, methods and visual proposals –as can be observed in the works in this retrospective– it has been an aspect in particular that has “commanded” her inquiries and she has recurrently returned on it in a good deal of her production, this is, the intransitivity of the photographic image. Said intransitivity is mainly referred to overcoming the glance which, facing a photograph, heads towards satisfying the desire for immediateness –in the words of Bolter and Grusin (2000)–, seeking to recognize the referent, objects and figures represented therein –the Barthesian studium– and dodging its mediated character[1].

In her early images, Bengoa reflected on the issue of intransitivity by searching in her own photographic image for that which exposed the significant condition of the medium, without suppressing the referential motive or component. This can be observed, for example, in 203 fotografías (1998), in which the very elements represented (bodily segments, folds and marks) allude to textures, shapes, tonalities, framings that invite one to observe and to think photography as a form of representation –and not as mere trace– of reality. In the piece en vigilia (1999) for its part, the proliferation of repeatedly similar photos triggers the oversight of the theme or object of the image (everyday, familiar, recurrent) in favor of the observation on chromatic and tonal variation, the almost unperceivable changes in the angle of view, the various foreshortenings and shapes appearing there. These exercises also reflected on the formats and the spatial disposition of photography, its set up, juxtaposition and expansion beyond the limit of the exhibition space (in the case of Tríptico en Santiago, 2000) as methods for environment research. Likewise, photography scrutinized its own limits when putting itself into tension –without combining– with other mediums such as painting, drawing and engraving, and also with issues related to the volumetric shape in the Bengoa’s works.

The latter turns out to be gravitating in the visual exercises Bengoa will execute for a good deal in the following decade; in them the artist will rehearse manual transcriptions of photographs onto non traditional supports, composed of materials as diverse as they are prosaic: dyed thistles, paper napkins, colored thread and felt cloths/remnants. Perhaps it is during these transfer exercises, in the medial and material transits of the image begun in 2001 with Sobrevigilancia, that the intransitivity of photography is more clearly and, maybe, sophisticatedly weighed and visualized.

I

During most of the 1990s, Mónica Bengoa worked with photographs that alluded to body views or parts, some of them alluding to her own image, be they singular portraits that showed the artist in disguise or adopting a masculine appearance, or captures of a body fragment in particular. As a result, there was a systematic accumulation of discarded photographs, remnants that were never exhibited. Nonetheless, these cuttings were recovered and collected toward the end of the decade in 203 fotografías, conforming a kind of small corporeal atlas. This work included images of a diverse nature offering partial and segmented views of the body.

Even if on a quite more modest scale, a part of the procedure used in 203 fotografías reminds us of Gerhard Richter’s Atlas project[2]: the appreciation of discarded images, their classification by subject, their variable juxtaposition, among others. As Benjamin Buchloh has pointed out in his illuminating text on the piece by the German artist (1999), the notion of atlas was appropriated by twentieth century art –and by art history from Warburg on– in a more metaphorical mode[3], even contravening its nineteenth century definition, which understood it as a comprehensive and all-encompassing form of systematization of knowledge in all areas of the empirical sciences. Beyond the scale of the projects and their intentions, the interesting thing is revealing the gesture mobilizing the production of these works, in which the access to the image does not happen in isolation, but in a more complex framework that places and signifies it. This network does nonetheless not pretend to be totalizing or holistic, but rather seems to insist on its fragmentary and arbitrary character. And even if the taxonomic will is undeniable, the accumulations and juxtapositions of photographs allow for a pluricentral visualization, in which there is no single or logical system of touring and observation.

Thus, Bengoa’s work triggers certain associations among the images that compose it, from more general views –half or whole body– to close-ups or zoom-ins of scars, cavities and folds in which it is hard to determine what part of the body is represented. Also, the spectator runs into focused images and some other blurrier ones, as Ricardo Cuadros noticed (1998) the first time the work was set up, different shutter lengths (speeds) can be made out[4]. Equally, different textures and forms appear, rhyming among themselves but also being out of tune. That is how in certain sectors of the set that which is lineal is weighed, generating a particular rhythm among images alluding both to a fold or scar as well as to the union of lips or eyelids. This contrasts with a group of photographs in which, instead of what is lineal, it is the shading or mezzotints that capture the gaze.

It is also interesting to view this repertoire not only as an essay on a possible image of what is corporeal, but also as a study on bodies as a support for inscription. In that sense a kind of mirror between the motive of the installation and photography in its most indicative is produced, in a certain way arguing with what has been stated in relation to an intransitive gaze on the photographic image.

II

And even if 203 fotografías presents a complexity for the spectator, since the point of view can continuously vary, questioning any pre-established syntax, in the photographs themselves there is no authorial aspiration, this is, there is no inscribed artistic intention, they are rather amateur, home-made photographs. The same happens with the images that make up en vigilia, the first in a series of projects in which Bengoa systematically photographs her children undertaking insignificant and routine activities: brushing their teeth, having lunch, or in this case, sleeping.

Susan Sontag wrote that one of the first and main popular uses of photography in the twentieth century was recording memorable family events (2006: 22-23): weddings, birthdays, holidays, etc. Thus, photographing family moments –especially if there were children– became a kind of social ritual whose objective was to symbolically commemorate and re-establish the ties among the members of the clan[5]. On the contrary, nothing exceptional happens in Bengoa’s images. What is captured are those blank spaces, without distress, but, nonetheless, turn out to be absolutely necessary in order to produce the contrast between what is ordinary and what is memorable. One could think, then, that that which is represented in en vigilia sees itself represented in that dilated and homogeneous time-lapse in which events take place are overcome and discarded almost immediately: it is profane time, placed in between the moments of use and the practice of photography as a family ritual. A paradox, or perhaps an inversion of terms, is thus introduced, since photography reserved for ceremonies is demystified by the routine and even obsessive use of the technical device.

This repetition to the point of exhaustion of the same motive (310 images in total and presumably other discarded ones), precisely triggers the question for the procedure and execution of the work: a sleepless mother, who night after night –without exception– captures her children’s rest. One can see the passing of time represented in the images, the wake marked by seasonal cycles, perceiving both the more evident (in the color and design of the bed sheets) as well as the less obvious (the length or style of the children’s hair). This theme of the body demanded in the production process will see itself intensified –and taken to the limit– in projects of a greater scale the artist will develop in the following decade, such as Sobrevigilancia (2001), enero, 7:25 (2004) or her ejercicios de resistencia (2002) series, just to give a few examples. In the same way, and even if the photographic installations mentioned above cover a quite significant surface, the blown up image to a mural scale will become recurrent in Bengoa’s work starting in 2000. It is specifically in Tríptico en Santiago (2000) where this change of format is confirmed, in the treatment of what is private and what intimate, already visualized in earlier proposals in relation to what is corporal and family centered, will reach considerable dimensions and will imply its positioning in public space.

III

Tríptico en Santiago is composed of three photographs in which the artist’s children are seen performing the same act (eating), in the same place (the kitchen) at different times. The images were installed on a tri-vision billboard at the street intersection of Bellavista and Loreto. Thanks to the mechanically controlled triangular prisms, repeated and regular rotation of the different photographs was possible, thus producing a singular triptych whose modules were never perceived in unison.

Contemporary artists had rehearsed artistic appropriation of urban advertising spaces years before, with Cuban Félix González Torres and his Billboard of Bed (1992)[6] as an emblematic case. Even if with quite different conceptual and visual intentions and proposals, in both works the same effect of strangeness is replicated facing an image whose function is transmitting a message immediately, but which on the contrary, turns out diffuse and undecipherable. The estrangement is produced because photography behaves ambiguously: because of its appearance and content it could perfectly comply with the aim of providing a product, but its mutism is disconcerting. In that sense, they are images, which are simultaneously placed in and out of context, operating under the visual logic of advertising but are at the same time distanced, turning ineffective.

In Tríptico de Santiago, the homemade photograph, devoid of splendor and the private and trivial scene enter into tension with maximum visibility and a central character of (public) space of location. Bengoa will explore this interesting divergence in several of her manual photographic image to non-traditional materials/supports transfer projects. As mentioned above, the first exercise in which the artist puts a transcription procedure to the test is in Sobrevigilancia, an installation of which there is only a visual registry and a few material vestiges.[7]

In this work, two interests converge, which had surrounded her for some years now. On one hand, and as we have seen, the research around the intransitivity of the photographic image, and on the other, the material explorations already observed in Cantidad y recurrencia: los vientos (2000) and in En Suspensión (2001), two murals of a quite different nature Bengoa made of natural flowers (thistles and evergreens).

During this artistic research process, Sobrevigilancia again highlights the issue of the vigilant gaze, which –as Sontag reminds us– saw itself intensified with the advent of the photographic device in the twentieth century and its manipulation in favor of the exercise of social control[8]. Even so, the attentive and vigilant gaze that filters into Bengoa’s image turns on what is trivial and insignificant, provoking a waste of technical resource. There, a perfectly normal bathroom sink sees itself represented in the mural, in which one can make out two small tooth brushes, toothpaste and a bar of soap. The question, then, is “what is that vigilant gaze aimed at?” or “with what aim is it really used for?”

Without a doubt, it is the transfer process of photography what demands an intense visual attention, meticulous and methodical. Even if the artist has taken advantage of computer programs in order to decompose the model image (which is never in sight for the spectator), elaborating templates in which the various color zones that conform the representation are delimited, the execution of the transfer is largely realized by rule of thumb. The procedure becomes even more complex if one considers the translation of photography is made toward a support made of dyed thistles, this is, something not traditionally known as an image medium. An unknown territory in which the technical and visual possibilities of the material in which the image is re-embodied are both explored and put to the test.

Thus, the question of what medium the photograph is transferred onto emerges, a pre medium, a new archaic medium? If Sobrevigilancia is put into perspective and observed in relation to certain murals in which Bengoa uses another type of materials and procedures in order to perform the photograph transference (hand colored napkins, thread stitches, cut out felt), it could be said that in each process different medialities appear: painting, engraving and drawing. Each mural then feeds from different aspects and characteristics of traditional media (color, line, texture, half-tones), without ascribing to any of them specifically. Thus, by means of the use of domestic materials, the artist has sought to simulate a conjunction of manual media to, at the same time, simulate the technical medium.

In these transfer exercises, intermediality, as Hans Belting understands it (2007), this is, the mutual influences (rivalries and dialogues) among the various media of the image, is stated as a way of studying its characteristics and specifics[9]. In the case of Sobrevigilancia, photography, on which the idea of a signifying transparency or neutrality has normally been poured on, de-hides its mediated condition by becoming, among other things, more pictorial. In this way, the thistle as a stain (irregular color unit) turns the outlines of the represented objects less sharp, making it hard to distinguish those elements supposedly in focus in the image. Thus, the immediateness imposed to the photographic medium is equally satisfied in the Bengoa’s work: referential objects are identifiable, but their simulated pictorialization, which for example, turns the toothbrush into a volumetric abstract green stain, makes the medium, and the media implied in it, simultaneously recognizable.

But the observation of the mural does not only behave like a visual demand for the spectator, the gaze also sees itself captivated by the sensual nature of the image. Despite the austerity of the chromatic palette, the dimensions of the work (9.160 thistles covering a total of almost fifty four square meters), the texture and the soft relief the dried dyed flowers contribute, tempt, provoke touch; impulse or reaction that struggles with self-moderation triggered by the weight of the gaze of the guard. From here on, Monica Bengoa’s works will, with ever increasing mastery, compensate the urgent study of the photographic medium with the sensory delight facing the image, which by means of the gaze, active in receptions that overflow and expand the mere visual in order to cover a bodily scale.

References

[1] Bolter, Jay David y Grusin, Richard. “Inmediatez, hipermediación, remediación”, en: Remediation: Understanding New Media, Eva Aladro (trad.), Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2000.

[2] An (ongoing) work in progress project initiated in 1962, in which the artist selects, classi es and orders an enormous diversity of photographic images, taken by himself, received as donations or extracted from printed media, into series. The over ve thousand photographs are organized in panels, collapsible units that are displayed on the wall in order to compose the Atlas.

[3] Buchloh, Benjamin. “Gerhard Richter’s Atlas: The Anomic Archive”. October, vol. 88, Cambridge: The MIT Press, p, 122.

[4] Cuadros, Ricardo. “Escenas de recuperación”, in: Exposiciones 1998, Santiago de Chile: Galería Posada del Corregidor, 1998, pp. 74-76.

[5] Sontag, Susan. Sobre la fotografía. México DF: Alfaguara, 2006, pp. 22-23.

[6] González-Torres installed the same monochrome photograph of an empty bed, whose pillows still retained the silhoue es of the heads that had lain there, on a series of di erent advertising billboards in New York.

[7] The dyed thistles that made up Sobrevigilancia were later reused in Persistence & de ection (2004).

[8] Sontag, op. cit., pp. 19-20.

[9] Belting, Hans. Antropología de la imagen, Buenos Aires: Kra Editores, 2007, p.63.

Published in m. [una tentativa de inventario exhaustivo, aunque siempre inconcluso], Santiago, Chile. Ed EUONIA, p. 113-117. 2017.