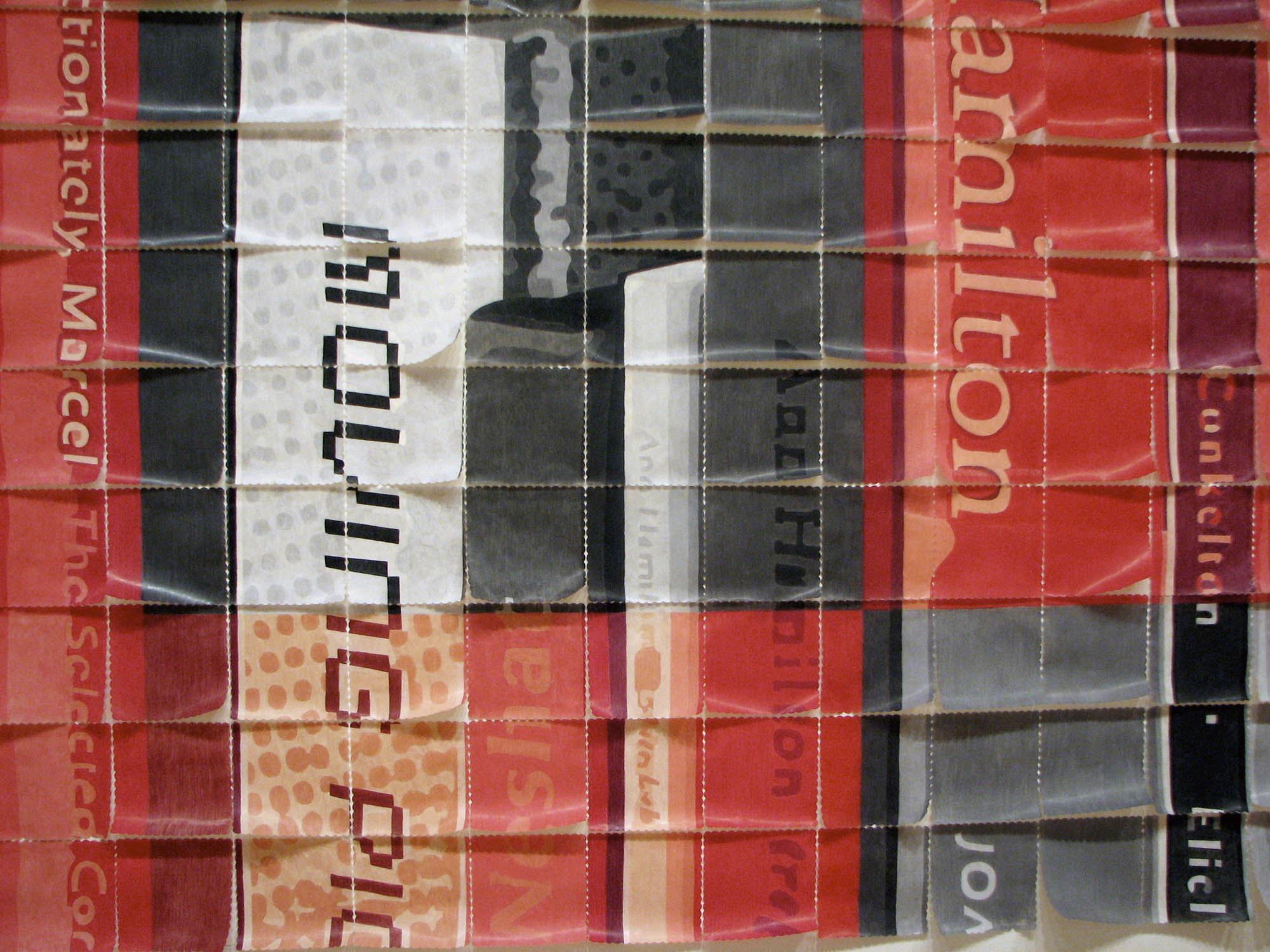

Los grandes murales fotográficos de Mónica Bengoa (…) son el resultado de un trabajo muy intenso. Construidos con millares de servilletas de papel, se han unido meticulosamente en una cuadrícula puesta en la pared. Las composiciones de sus obras recuerdan los grandes foto-colages de David Hockney, pese a que la intimidad del tema tratado –que incluye la realidad de las paredes domésticas, los juguetes de sus niños y los objetos de cocina– contraste con el tamaño de sus obras. La fusión entre su identidad de madre y de artista y los aspectos cotidianos de esos papeles, representan su principal fuente de inspiración.

Su reciente obra W, Así lo veo yo (o el gran cuaderno de instrucciones de uso de un aficionado a clasificar las cosas), 2006-2007, cubre una pared entera y muestra lo que la crítica Julia Herzberg describe como cualidades “intensas, efímeras y personales” [1]. W, Así lo veo yo representa la sección de la biblioteca de la artista en la que figura una selección de sus libros preferidos. La obra, cuyo título procede de una especie de juego de palabras obtenido de la unión de los títulos de algunos de los libros presentes en los estantes, y que disfruta de su misma vida como fuente de inspiración, ofrece una visión íntima de la personalidad y del intelecto de la artista. Si se efectúa un análisis del título se puede deducir que “W” representa el título W, ou le souvenir d’enfance (1975), biografía del escritor francés Georges Perec [2], mientras “Así lo veo yo” alude a la segunda parte de la autobiografía de David Hockney, That’s the way I see it, publicada en 1993. “El gran cuaderno” se refiere a la primera novela de Agota Kristof, Le grand cahier (1987), primer libro de una trilogía que incluye Le preuve (1988) y Le troisème mensonge (1991) [3]. La expresión “de uso” deriva del título del libro más famoso de Perec, La vie, mode d’emploi (1978). También la palabra “aficionado” se refiere a un título de Perec, Un cabinet d’amateur (1979), así como “clasificar” procede de Penser, classer (1985) y “las cosas” de su primera novela Les choses. Une histoire des annèes soixante (1965). Imitando el amor de Perec por los palíndromos, los acrósticos y los anagramas, M. Bengoa nos muestra a través del título de la obra su apreciación por la lectura y nos ofrece también la posibilidad extraordinaria de investigar su vida. En efecto las historias citadas pueden ser autobiográficas o tratar acerca de niños, o las dos cosas a la vez. Los niños representan un argumento en el que la artista está muy interesada y efectivamente hasta hoy, la mayor parte de su obra es autobiográfica, o bien trata de niños o las dos cosas simultáneamente.

Al explicar la naturaleza de su trabajo, la artista con modestia afirma que su objetivo es “registrar situaciones que no son memorables, que no sobresalen en una historia familiar pero, si, resaltan porque son historias normales y no distintivas” [4]. Cuando escribe sobre la exposición de M. Bengoa preparada en el Latincollector Art Center de Nueva York en 2004, Herzberg subraya que ella, igual que otros artistas entre los cuales Duchamp y Warhol, “nos vuelven a recordar la importancia de lo ordinario como elemento distintivo del arte” [5]. La sección de la biblioteca de M. Bengoa a la que tenemos acceso refuerza esta noción. Hablando de su atracción por las obras escritas de Perec y Kristof, la artista explica que “sus estilos de escritura parecen transmitir una manera de hacer las cosas que yo misma quiero reflejar en mis obras. Estoy hablando de una especie de distancia emotiva (que no es excesiva) que permite mantener una cierta frialdad (abandonando el enfoque dramático) cuando se utiliza su propio espacio privado en el trabajo y, por otro lado, me atrae mucho la manera en que Perec considera las cosas inútiles; me identifico mucho con este aspecto” [6]. Es obvio que M. Bengoa comprende, como escribe la crítica Yu Yeon Kim, “la poderosa resonancia de las cosas pequeñas” [7] y su fuerza iterativa; los límites físicos de su taller y de su casa son suficientes como fuente de inspiración para la realización de sus obras.

[1] Julia Herzberg, “Mónica Bengoa: The color of the garden”, en «Mónica Bengoa: The color of the garden», folleto de la exposición (Latincollector Art Center, Nueva York, 2004), p.n.n.

[2] Se conocía muy bien el interés de Georges Perec por los palíndromos, los anagramas y los juegos de palabras, que utilizó en muchas de sus novelas.

[3] Después de huir de Hungría en 1956, Agota Kristof y su marido se establecieron en Ginebra. Durante su estancia en Suiza, Agota Kristof aprendió francés como autodidacta y empezó a escribir utilizando esta lengua. Además de las novelas, escribió también algunas obras de teatro.

[4] Mónica Bengoa, correo electrónico para la autora, 3 de mayo 2006. Yo misma me he ocupado de éste y de las sucesivas traducciones de la correspondencia electrónica con la artista.

[5] Herzberg, Mónica Bengoa: The color of the garden cit.

[6] M. Bengoa, correo electrónico para la autora cit.

[7] Yu Yeon Kim, “Monumental Fragility: The Work of Mónica Bengoa”, en Mónica Bengoa; cuaderno en mano, (autopublicación, Santiago 2004), p.n.n.

Alma Ruíz

Curadora

Art Is Made by the Hands. Alma Ruiz. Catálogo de la exposición Poetics of the Handmade, p.14-16. Los Angeles, CA., United States. 2007

Art is Made by the Hands

Deriving from a labor-intensiveness (…) are Mónica Bengoa’s large photographic murals. Constructed out of thousands of hand-colored cocktail napkins, her murals are meticulously assembled on a grid on the wall. The overall compositions of her works bring to mind David Hockney’s large-scale photo-collages, though the intimacy of her subject matter –which includes domestic interiors, her children’s toys, and household items– contrasts with her works’ scale. The conflation of her identity as both a mother and an artist, and the quotidian aspects of these roles, provides Bengoa her main inspiration.

Bengoa’s recent work W, Así lo veo yo (o el gran cuaderno de instrucciones de uso de un aficionado a clasificar las cosas) (W, that’s the way I see it [or the notebook, a user’s manual of an amateur who classifies things], 2006-07) covers an entire wall and exhibits what critic Julia Herzberg described as “labor intensive, ephemeral, and personal” qualities [1]. W, Así lo veo yo depicts the section of the artist’s library that contains a selection of her favorite books. Deriving its title from a sort of wordplay formed by stringing together the titles of some of the books, the work, which mines her own life for inspiration, offers an intimate view into the artist’s personality and intellect. Deciphering the title, “W” stands for W, ou le souvenir d’enfance (W, or the memory of childhood, 1975), a memoir by French writer Gorges Perec [2]. “Así lo veo yo” refers to the second part of David Hockney’s autobiography That’s the way I see it, published in 1993. “El gran cuaderno” refers to Agota Kristof’s first novel Le grand cahier (The notebook, 1986), the first book in a trilogy that includes La preuve (The proof, 1988) and La troisième mensonge (The third lie, 1991) [3]. The phrase “de uso” comes from the name of Perec’s best-known book, La vie, mode d’emploi (Life: A user’s manual, 1978). The word “aficionado” also refers to a title by Perec, Un cabinet d’amateur (A gallery portrait, 1979); “clasificar” is from his Penser, classer (1985) and “las cosas” from his first novel Les Choses: Une histoire des années soixante (Things: A story of the sixties, 1965). Imitating Perec’s love of palindromes, acrostics, and anagrams, Bengoa offers us through her title not only an appreciation for reading, but also the rare possibility of delving deeper into her life –the stories referenced are autobiographical in nature and/or involve children, subjects of great interest to Bengoa; most of her work to date is based on one or the other, or both.

Explaining the nature of her work, Bengoa modestly asserted that she aims to “record situations that aren’t memorable, that do not stand out in a family’s history; rather, they take hold because they are not distinctive but just normal” [4]. Writing about Bengoa’s 2004 exhibition at Latincollector Art Center in New York, Herzberg noted that Bengoa, like artists including Duchamp and Andy Warhol, has “made us think anew of the importance of the ordinary as a defining element of art” [5]. Bengoa’s library piece seems to reinforce this notion. In discussing her attraction to the writings of Perec and Kristof, Bengoa explained that “their writing styles seem to transmit a manner of doing things that I am very interested in having reflected in my own work. I am referring to a certain emotional distance (not too much) that allows one to avoid being dramatic when one utilizes one’s own private space to work, and on the other hand, I am also very interested in how Perec pays attention to banal things, I truly identify with that” [6]. It is obvious that Bengoa understands, in the words of critic Yu Yeon Kim, “the powerful resonance of small actions” [7] and their iterative strength; the physical limits of her studio and her home provide sufficient inspiration for her work.

[1] Julia Herzberg, “Mónica Bengoa: The Color of the Garden,” in Mónica Bengoa: The Color of the Garden, exh. brochure (New York: Latincollector art center, 2004), n.p.

[2] Georges Perec was known for his fascination with palindromes, anagrams, wordplay, and word games, which he used in many of his novels.

[3] After fleeing Hungary in 1956, Agota Kristof and her husband settled in Geneva. While living in Switzerland, Kristof taught herself French and began to write in that language. In addition to novels, Kristof has also written novels and plays.

[4] Bengoa, email to the author, 3 May 2006. This and all subsequent translations of email correspondence with the artist are mine.

[5] Herzberg, “Mónica Bengoa: The Color of the Garden.”

[6] Bengoa, email to the author.

[7] Yu Yeon Kim, “Monumental Fragility: The Work of Mónica Bengoa”, in Mónica Bengoa: Cuaderno en Mano (Santiago: self-published, 2004), n.p.

Art Is Made by the Hands. Alma Ruiz, in Exhibition catalogue Poetics of the Handmade, p.14-16. Los Angeles, CA., United States. 2007