Una creadora visual más reciente que ha puesto en cuestión la consistencia y presencia del cuadro como soporte, es la artista Mónica Bengoa (1969), para quien el cuadro no es otra cosa que el fruto de los sucesivos desplazamientos de referentes previamente fotografiados.

En 1999 inició una exploración sobre la puesta en escena de la vida cotidiana familiar, registrando regularmente acciones domésticas reglamentadas. Para ello, clasificó actividades relacionadas con elementos familiares diferenciados (herramientas domésticas, mobiliario, ropa de cama) y produjo regularmente registros fotográficos, buscando las sutiles diferencias que tenían lugar en la realización de cada fotografía según el espacio y el tiempo específico de cada toma.

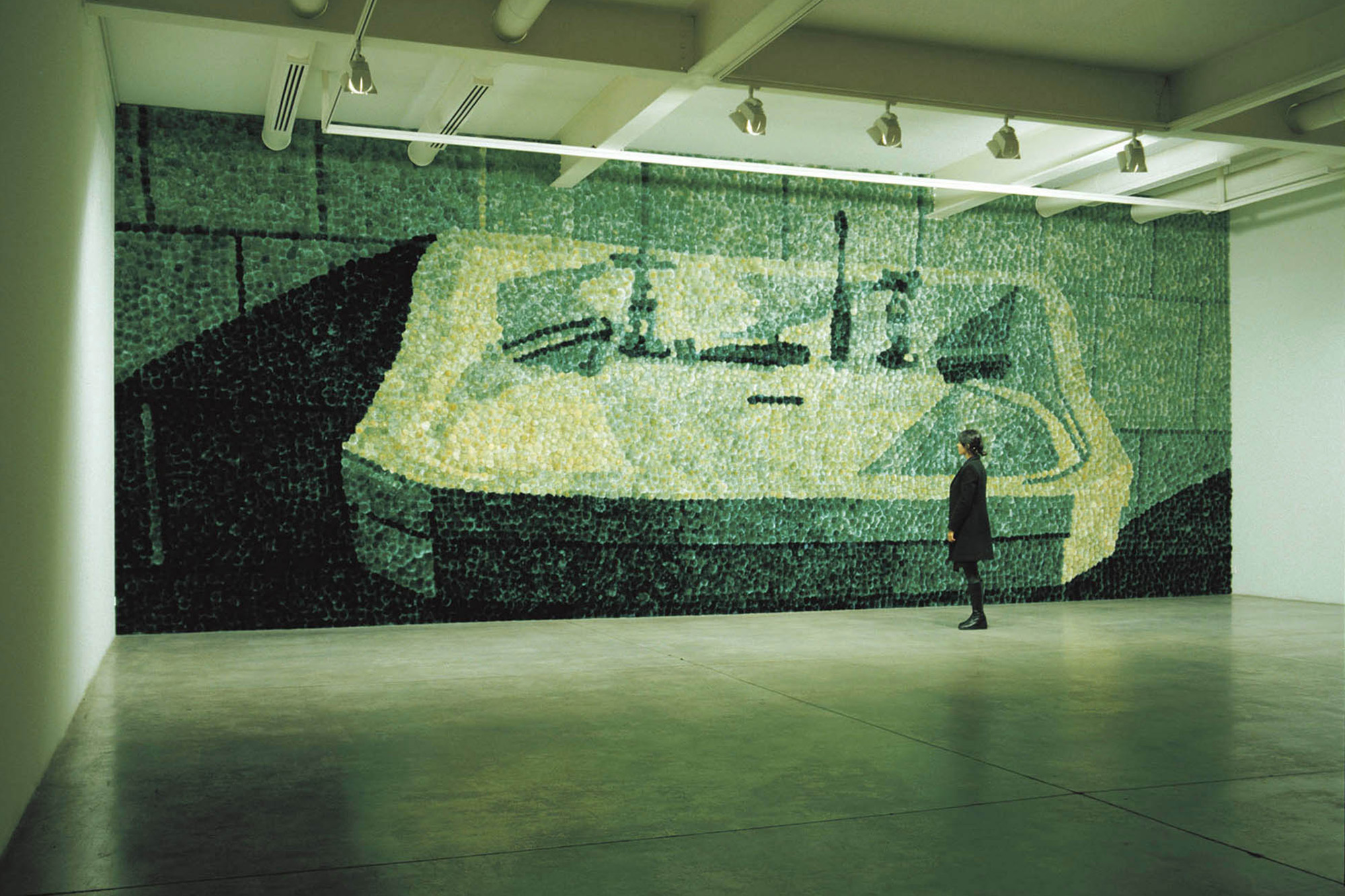

El tema de su obra Sobrevigilancia es la imagen del lavamanos en el baño familiar, sobre el cual se encuentran dos cepillos de dientes infantiles, un tubo de crema dental y un jabón. Esa obra monumental, de 54 metros cuadrados de superficie, fue constituida por cientos de flores de cardos secos, unidas y apretadas unas contra otras, que pegó a muro de la galería donde se exhibió, formando una superficie unitaria. Sobre esa superficie punzantemente agresiva, la artista desplazó el tema de la fotografía del baño familiar, que seducía el ojo del espectador a través de su textura y el color verde que caracteriza la fotografía amateur, técnicamente deficiente. “A partir de ese trabajo”, dice la artista, “fue posible radicalizar el sistema de construcción de obra, asumiendo decisiones significativas en cuanto a las modalidades y materialidades de transferencia de imágenes fotográficas”.

Mónica Bengoa sustituyó la institucionalidad del paño de la tela y el bastidor que la soporta, al pegar directamente en la muralla los cardos que, pintados y numerados de acuerdo a un plan de trabajo, “armarían” una pintura y no un cuadro. Hay que considerar la mirada del espectador, y sobre todo la de primeros planos, donde el que miraba se encontraba con la particular textura de la planta seca, con sus intersticios y “profundidades”, y a medida que se alejaba para observar esa monumental obra, comenzaba a aparecer la pintura como unidad temática y formal. Por los significantes empleados en ese mural, se trataba de una obra efímera, ya que la flor de cardo no solamente estaba propuesta como soporte, sino que era parte constitutiva y significante de esta obra pictórica. Cuando la exposición terminó, la artista debió “desmontar” la pintura y despegar uno a uno los cardos significantes que, en cuanto soportes, le daban a la obra un corpus de absoluta fragilidad.

Bengoa investiga “puentes de intercambio material” con otros medios, invirtiendo estrategias formales provenientes del dibujo y la pintura e incluye el uso de objetos. Esos objetos, acumulados, redistribuidos, seriados y haciendo masa, le permitieron crear dispositivos de traslado eficientes para la producción de grandes murales. Flores naturales, servilletas de papel y otros son el soporte para reproducir la estructura fotográfica de origen.

Para la artista, el traspaso de un lenguaje a otro obedece también a la elaboración de un sistema de restricción en el uso del color, derivado de prácticas minimalistas programáticas y formales. “Las flores de cardos, por ejemplo”, explica, “se constituyen en un píxel fotográfico o pincelada seuratiana. Ello permite la incorporación de módulos-objetos mediante procedimientos ligados a prácticas posminimalistas, en términos de repetición y de construcciones reticulares, como también el uso del medio fotográfico como sistema ortopédico de construcciones de imágenes…”.

Otra obra suya, que expuso en la galería Gabriela Mistral, se titula Enero, 7:25. En ella estableció una organización cromática, basada en las distorsiones lumínicas generadas por la fotografía digital traspasada a la pantalla del computador. Esas distorsiones, que se instalaron como referente cromático de la imagen, a su vez fueron desplazadas hacia otro soporte: la servilleta de papel. La artista reiteró las operaciones de transferencia de imágenes fotográficas hacia otras materialidades, e incluyó procedimientos ligados a desplazamientos del dibujo y del grabado. La servilleta de papel le sirvió de módulo para hacer visible, en gran formato, la imagen que mostraba una cama de niño desarmada, vista a ras de suelo, bajo la cual se encontraban escondidos juguetes y vestimentas. Usó cientos de servilletas de papel, que fueron coloreadas con lápices de colores, siguiendo la restricción cromática que la fotografía impone.

“Podría decirse que Enero, 7:25 establece una relación inversa en cuanto a la utilización del instrumento óptico”, señala Bengoa, “ya que el propósito no se basa en su poder de crear imágenes lo más fieles posibles a la realidad, sino en revelar el procedimiento técnico de la elaboración de obra”. Para la artista, la consistencia de la imagen en la obra monumental –que se produce en la mirada lejana– abre preguntas sobre la eliminación del soporte del cuadro, y también sobre los procedimientos que la artista practica para traspasar el referente de la escena original fotografiada, reproducida y deformada en el computador. Cientos de servilletas que se movían permanentemente al menor roce fueron el “soporte” sobre el cual se buscó traducir lo más fielmente posible esa imagen. El trabajo proponía como problema el cruce entre la imagen producida mecánicamente y la manualidad, que reproducía el referente fotográfico del escenario doméstico. También estaba la manualidad del gesto, repetido insistentemente, y el gran formato.

Enero, 7:25 presentó lo que se hace visible a escala monumental, sobre la fragilidad de cientos de servilletas pegadas al muro. Pero a medida que el espectador avanzaba, el módulo –en su esencia frágil e inservible y sobre el cual se reproducía, como ínfimo fragmento, el pintar con lápices de colores– iba adquiriendo significado. La servilleta asumió el doble papel de soporte y significante; las servilletas pegadas sobre el muro organizaron una particular textura y conformaron un “cuadro” frágil y efímero.

Gaspar Galaz

Escultor e historiador del arte

Desplazamientos singulares en La Pintura se interroga en Pintura en Chile 1950 – 2005 Grandes temas. Galaz, Gaspar, p.160-163. Santiago: Ed. Cecilia Valdés. 2005

Singular displacements

A more recent visual artist who has questioned the issue of the consistency and presence of the painting as a support, is artist Mónica Bengoa (1969), for whom the painting is nothing but the outcome of successive displacements of previously photographed referents.

In 1999, she began an exploration of the staging of everyday family life, regularly recording regulated domestic actions. To that end, she classified activities related to differentiated family elements (domestic tools, furniture, bedding) and regularly produced photographic records, looking for the subtle differences that took place in the making of each photograph according to the specific space and time of each take.

The theme of her work Sobrevigilancia (Overvigilance) is the image of the sink in the family bathroom, on which there are two children’s toothbrushes, a tube of toothpaste and a bar of soap. That monumental work, of a fifty-four square meter surface, was built with hundreds of dry thistle flowers, tightly wrapped one against the other, which she affixed to the gallery wall where it was exhibited, forming a unitary surface. Onto that pointedly aggressive surface, the artist displaced the issue of the photograph of the family bathroom, which seduced the eye of the viewer through its texture and the green color that characterizes amateur photography, technically deficient. “From this work onwards”, the artist says, “it was possible to radicalize the work construction system, assuming significant decisions in terms of the modalities and materialities of the transference of photographic images”.

Mónica Bengoa substituted the institutionalism of the canvas and the frame that supports it by gluing the thistles directly onto the wall, which, painted and numbered according to a work plan, would ‘assemble’ a painting and not a tableaux. One has to consider the glance of the spectator, and above everything, the one on foreground, where who was looking at it was confronted with the particular texture of the dry flowers, with its interstices and “depths”, and as he or she moved away to observe the monumental work, a painting as a thematic and formal unit emerges. Due to the signifiers implied in that mural, it was an ephemeral work, since the thistle flower was not only being proposed as support, but was a constituent and meaningful part of this pictorial work. When the exhibition came to an end, the artist had to “un-mount” the painting and one by one detach the signifying thistles, which, as supports, gave the work a corpus of absolute fragility.

Bengoa investigates “bridges of material exchange” with other means, inverting formal strategies from drawing and painting, as well as including the use of objects. These objects, accumulated, redistributed, serialized and becoming a mass, allowed her to create efficient transfer devices for the production of large murals. Flowers, paper napkins and others are the support for reproducing the photographic structure of origin.

For the artist, the transference from one language to another also obeys to the elaboration of a system of color use restriction, derived from minimalist programmatic and formal practices. “The thistle flowers, for example”, she explains, “are constituted in a photographic pixel or seuratian brushstroke. This allows the incorporation of modules-objects through procedures linked to post-minimalist practices, in terms of repetition and reticular constructions, as well as the use of the photographic medium as an orthopedic system of image constructions…”.

Another work of hers at the Gabriela Mistral gallery is titled Enero, 7:25 (January, 7:25). In it she established a chromatic organization based on the distortions generated by digital photography transferred to the computer screen. These distortions, which were installed as chromatic referents of the image, were at the same time displaced to another support: the paper napkin. The artist reiterated the operations of transference of photographic images to other materialities, and included procedures linked to displacements from drawing and engraving. The paper napkin served her as a module to make the image showing an unmade children’s bed visible, seen from ground level, under which there were hidden toys and clothes. She used hundreds of napkins that were colored with color pencils, keeping with the chromatic restriction photography imposes.

“It could be said that Enero, 7:25 establishes a inverse relation as far as the use of the optical instrument”, Bengoa states, “since the purpose is not based on its power of creating images as realistically accurate as possible, but on revealing the technical procedure of the elaboration of the work”. For the artist, the consistency of the image in the monumental work –produced within the distant glance– opens questions on the elimination of the picture support, as well as on the procedures the artist practices to transfer the referent of the original photographed scene, reproduced and deformed with the computer. Hundreds of paper napkins permanently moving at the slightest touch were the “support” on which the artist sought to translate that image as accurately as possible. The work proposed the crossing between the mechanically produced image and manual labor, which reproduced the photographic referent of the domestic stage. There was also the manual labor of the gesture, repeated insistently, and the great format.

Enero, 7:25 presented what becomes visible on a monumental scale, on the fragility of hundreds of paper napkins affixed to the wall. But as the spectator advanced, the module –in its fragile and useless essence on which the act of painting with color pencils was reproduced as a tiny fragment– went on to acquire meaning. The napkin assumed the double role of support and signifier; the napkins affixed on the wall organized a particular texture and conformed a fragile and ephemeral “painting”.

Gaspar Galaz

Sculptor and art historian

La pintura se interroga (in painting one interrogates) published in Pintura en Chile 1950-2005, Grandes temas (painting in Chile, 1950-2005, great issues), pg. 160-163, Santiago, Cecilia Valdés, publisher.