REALITY FOTOGRÁFICO

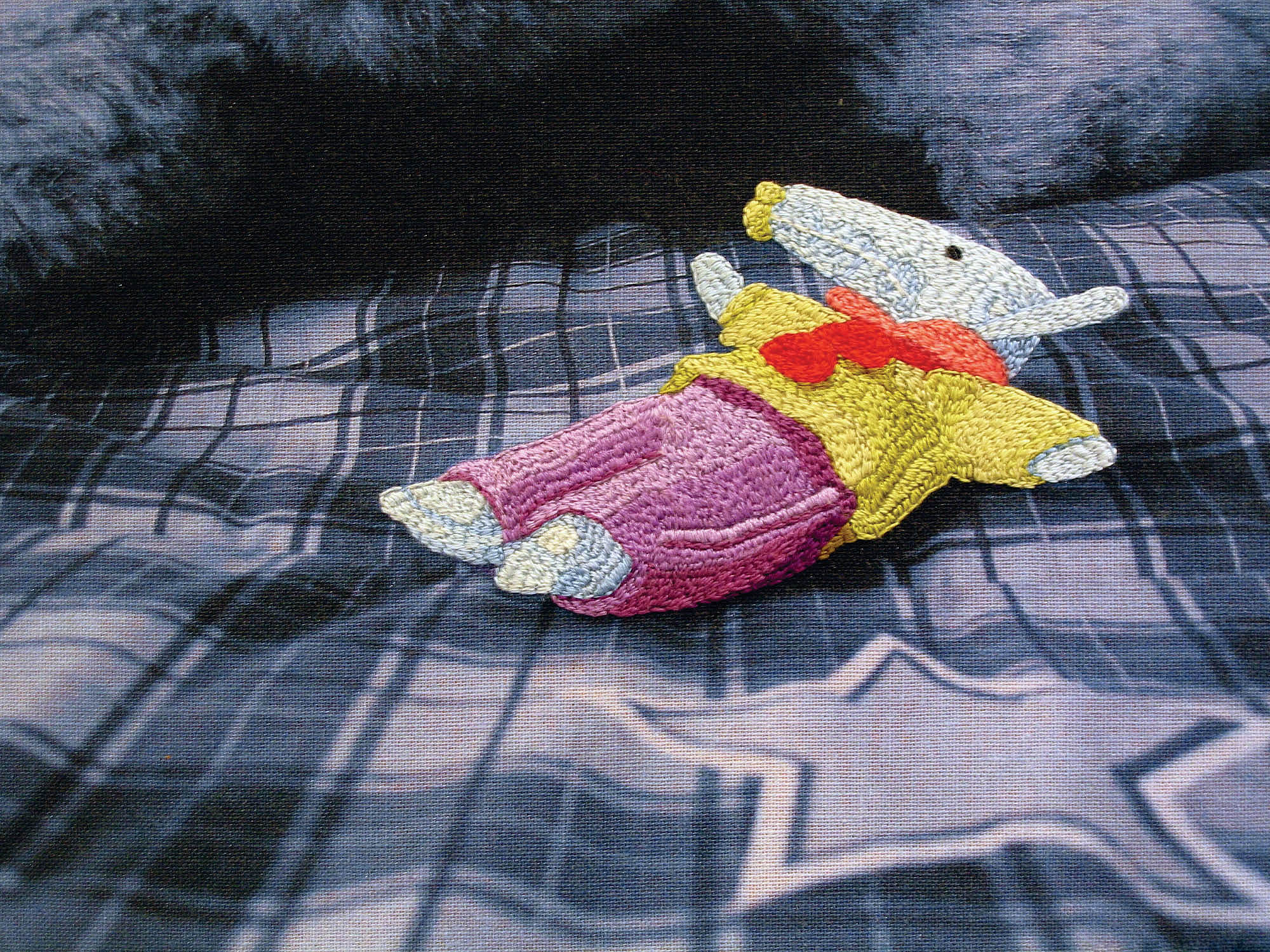

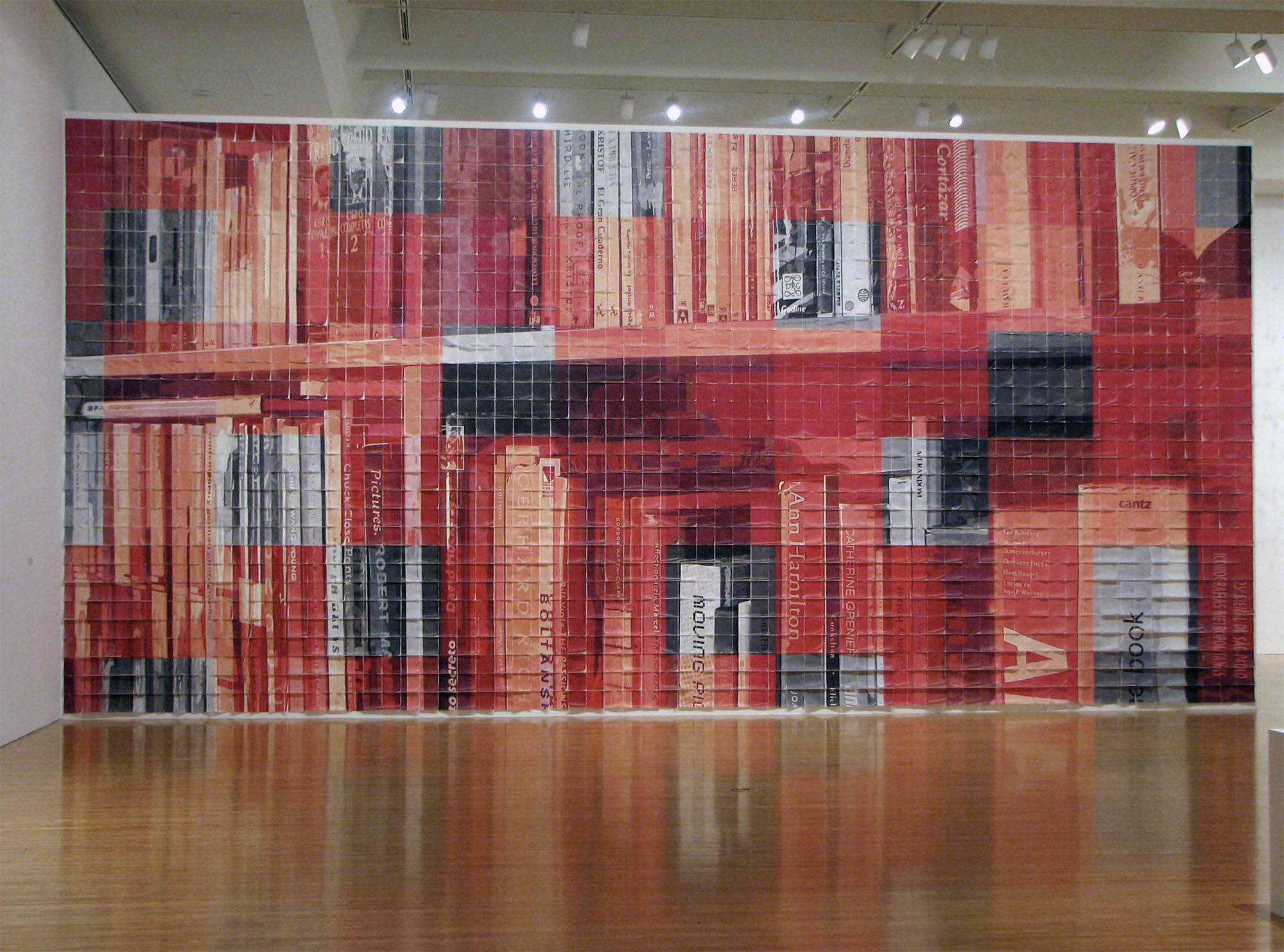

Mónica Bengoa ya está aburrida de que encasillen su obra en el tema autobiográfico. La artista, reconocida por llevar tomas hogareñas a grandes series fotográficas y murales, dice que hace rato dejó de centrarse en el retrato de su cuerpo y del mundo doméstico, para jugar con los traspasos técnicos de imágenes privadas que soportan puestas en escena colosales. Más que elaborar una especie de álbum personal con registros de ella durmiendo, de sus hijos lavándose los dientes o de las ollas en la cocina –cosa que sigue haciendo–, lo que presenta es el resultado de todo un proceso, donde la instantánea ha sido ampliada en el computador, transfigurada en códigos cromáticos, bordada o pintada con lápices de colores sobre cientos de servilletas de papel que van pegadas a la pared.

“Me interesan los cruces, un trabajo que al mismo tiempo pueda ser objetual y dibujo, pictórico y fotográfico, y que se instale con cierta presencia en el muro. Yo creo que está un poco obsoleto tratar de encasillar las cosas en disciplinas y justificar todo desde ahí. Esto es foto. Esto es pintura. Me interesa cuando es lo más híbrido posible”, enfatiza.

Lo que esta autora hace es “posfotografía”. Una tendencia internacional que se situó definitivamente en Chile en los ’90, y que cuenta con antecedentes locales en la obra de Eugenio Dittborn, en textos de Ronald Kay y en operaciones desplazatorias provenientes del grabado, donde la fotografía se vuelve material plástico y de reflexión.

Bengoa manipula las fotos hasta volver “lo cotidiano” en una escena impactante y paradojal, apuntando a ámbitos como la manualidad y la tecnología, lo público y lo privado; o “lo real”, visto a través de grandes “pantallas”. En Tríptico en Santiago, la idea fue llevada a un extremo: tres tomas de sus hijos comiendo en la cocina, lucieron por un mes en un panel publicitario monumental –de ésos que van cambiando la imagen– ubicado en Bellavista con Loreto. “El contraste entre esa máxima exposición de la intimidad, de la fotografía de bien bajo perfil en un soporte hecho para albergar imágenes generalmente de alta calidad y bastante espectaculares, me permite hablar de esas acciones cotidianas que construyen un territorio de seguridad, pero que pasan inadvertidas”.

Es una mirada sobre la intimidad a la distancia. Un particular reality inspirado en el estilo de Agota Kristof en “El gran cuaderno”, libro que “La Troppa” llevó al teatro a través de “Gemelos”: “Esa lejanía máxima para hablar de las cosas más terribles, me interesa mucho. Esa austeridad para el tratamiento de lo doméstico, también. Tiene que ver con adoptar una distancia intermedia que permita estar involucrada personalmente, pero abierta como para que el público se sienta invitado a participar”.

CUERPO DE BATALLA

La artista deja claro que prefiere la narrativa a la lectura de textos de filosofía, estética o teoría del arte. Tanto así que “Lumpérica”, de Diamela Eltit, “fue el primer acercamiento al cuerpo como territorio de batalla”. Era un tiempo en que Mónica Bengoa era “fan” de Cindy Sherman (artista neoyorquina reconocida por sus retratos que ligan la situación social de la mujer con cierto horror). Sus obras del período universitario pasaban por la preocupación sobre el cuerpo. Entonces vinieron los autorretratos; luego, los acercamientos a la piel, los pliegues, los lunares, las cicatrices, las espaldas de familiares y amigos, también estaba el trabajo con murales pintados con lápices de colores restringidos a la gama de una carta climática. La fotografía y el mural, la cartografía corporal y la cartografía terrestre. Eran trabajos paralelos que representaban –en distintas escalas– una cosa de territorio que luego cruzaría en Sobrevigilancia, la escena del lavamanos recreada con cardos pigmentados.

–¿Por qué comienzas con grabado?

“Fue una excusa que se debió a un interés de grupo. Mario Navarro, Cristián Silva, entre otros, nos metimos todos juntos. También Francisca García y Carlos Navarrete. Fundamentalmente fue por Vilches. Él era uno de los precursores del área, un profesor que nos dio la oportunidad de trabajar con un cruce de medios impresionante, y con un desarrollo conceptual mucho más amplio. Entonces, el grabado nunca fue tan grabado y siempre estuvo mezclado con fotografía”.

– ¿Qué similitudes tenían como grupo? ¿Temas comunes?

“Una cierta posición política frente al quehacer más que una temática puntual. Bueno, fuimos compañeros desde primer año, sacamos la misma especialidad, nos formamos de igual manera, con intereses comunes en literatura, cine… Teníamos una manera de entender el arte como ejercicio, no como la obra maestra resuelta. Como un trabajo en el tiempo; una investigación que se va acumulando y corrigiendo, y que va cometiendo nuevos errores para volver a trabajarlos con un pie forzado”.

– ¿A qué te refieres con “pie forzado”?

“Me refiero a que cada nuevo trabajo involucre algún tipo de desafío, algo que no se controla, y que uno hace por primera vez, estableciendo una especie de protocolo, un cierto sistema de operaciones donde se está tremendamente alerta del contexto donde se va a instalar el trabajo, no sólo espacial, sino cultural”.

Hacerse cargo del contexto: influencia de Eugenio Dittborn.

“Él hizo un taller súper importante. Y no es casual que lo haya hecho por primera vez cuando fui alumna de la escuela, por el ’90. Eugenio armó los grupos, y por entonces empezamos a trabajar juntos con el Mono (Cristián Silva) y Mario. Yo creo que fue uno de los profesores que nos abrió más la conciencia sobre el lugar específico donde instalar el trabajo. Al punto de que teníamos que saber las dimensiones exactas de la sala, lo que había entre pilar y pilar, etc.”.

JEMMY BUTTON

Dice la artista:“Yo creo que mi inserción (en el circuito) ha sido paulatina y siempre con una cuota de suerte. Nunca mi energía ha estado puesta en el tema. Jamás he sido de esas personas que persiguen a los curadores, que mandan miles de currículums y de catálogos a mucha gente. Pero sucede que uno va a exponer afuera, y esa muestra la ve alguien que luego se interesa y te llama. Trabajo mucho, expongo harto y eso me ha dado mayor circulación”.

–¿Cómo conseguiste las primeras exposiciones?

“Mi generación fue súper movida. Ya estábamos exponiendo en un montón de partes desde la escuela. Nosotros abrimos espacios. Expusimos en esa sala que había en Renca, en el Museo Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna, en los institutos binacionales. Luego que salimos (1993), con el Mono, el Mario y el Justo armamos ‘Jemmy Button’, que fue fundamental. Como siempre aquí se da mayor relevancia a quienes han expuesto afuera, siento que nos colgamos un poco de eso y empezamos a contactar a quienes podían estar interesados en nuestro trabajo. El ’94 fuimos a Holanda y tuvimos nuestro primer Fondart”.

–Pero si estaban con Justo Pastor Mellado, empezaron arriba se puede decir.

“Aunque se enoje, yo creo que ha estado un poco sobredimensionado lo que hizo con nosotros. Es verdad que formaba parte del grupo casi de igual a igual. Él nos llevó como Jemmy Button a Curitiba (1995, XI Muestra de Grabado, Brasil). Pero el resto de cosas fue gestión nuestra. Esa exposición en Holanda la conseguimos gracias a que el hermano del Mono vivía allá. El ’96 fue más o menos lo mismo. Sin conocer a nadie, mandamos nuestro dossier a la embajada en Londres. ‘Taxonomía’ (uno de los trabajos más importantes del colectivo) fue un libro que se nos ocurrió a nosotros. En el fondo (Mellado) se limitaba a escribir acerca del proyecto. Nunca se metió con las obras”.

AL BORDE DEL FEMINISMO

Con las artistas Claudia Missana, Paz Carvajal, Alejandra Munizaga (en un primer momento) y Ximena Zomosa, Mónica Bengoa ha realizado proyectos específicos sin condicionar su trabajo individual. “Proyecto de borde” ha sido otra “alianza estratégica” que le ha permitido alcanzar ciertos lugares a los que no habría podido llegar sola. Fue así como conoció la galería de NY con la que estuvo trabajando, Latin Collector, que además la llevó a Arco, la feria de Madrid.

–Jemmy Button representa cierto conceptualismo más duro y este grupo de mujeres da muestra de un trabajo dotado de otra sensibilidad. ¿Estas alianzas hablan de oscilaciones en tu obra o estás situada en dos territorios?

“Yo me siento absolutamente cómoda exponiendo con cualquier persona. Pero tuve muchas aprensiones con estar en ‘Proyecto de borde’, porque me molestaba mucho esto de que fuéramos puras mujeres y me sigue causando problemas. Pese a que trabajamos súper bien y hay gran respeto mutuo, tenemos visiones distintas. Yo no me siento en terrenos del feminismo, porque no me interesa ni la posición de víctima ni de superhéroe. Necesito situarme en el terreno intermedio de la normalidad”.

–Y algunas del grupo, ¿son algo feministas?

“Sí. Siempre tengo que estar dando una opinión centrada, pidiendo que bajemos un poco el tono a la cosa feminista porque a mí no me interesa. Es un trabajo hecho por una mujer y se nota a diez kilómetros. Pero no está ahí puesto el acento. Sin embargo, otras del grupo son bastante conceptuales y ligadas al lenguaje, muy rigurosas y con investigaciones súper fuertes. Yo probablemente esté en la mitad”.

–A nivel internacional, te has manejado con algunos curadores importantes (como la coreana Yu Yeon Kim). ¿Cómo te has relacionado con la crítica en Chile?, ¿has trabajado con algún teórico además de Justo Pastor?

“La verdad es que haber estado ligada a él, me ha traído más problemas que ventajas. Él es un personaje súper polémico, que causa mucha desconfianza en varios ámbitos. Como he estado tanto en tránsito, me he mantenido un poco afuera de estas rencillas y bastante independiente. Pero, lamentablemente, se me sigue ligando a él. Ahora vuelvo a trabajar con alguien (con Adriana Valdés en ‘Enero, 7:25’). Y yo diría que por primera vez trabajo en conjunto, ya que Justo, de alguna manera, se hacía una visión de la obra, y escribía sin preguntar mucho acerca de lo que estás efectivamente planteando”.

POLÍTICAS PRIVADAS

–¿Cómo has asumido los cambios políticos y culturales de la posdictadura?

“El aspecto público-político no ha estado en el ámbito temático. No por falta de interés en lo que ha pasado. Al contrario. Siempre trato de estar tremendamente alerta de lo que ocurre alrededor. Mi trabajo tiene que ver con otro tipo de políticas. Privadas, por decirlo de algún modo. Yo creo que la necesidad de extender los límites de la fotografía pasa por estar presente, y por cierta noción de verdad que el lenguaje puede transmitir”.

–¿Cómo te ha influido el desarrollo de la institucionalidad cultural?

“Sinceramente, creo que estos últimos años he estado un poco afuera. Porque he viajado harto, pero también por aburrimiento. Porque siento que (en el mundo del arte) hay muchas cosas que se arrastran y que hoy en día no tienen ninguna razón de ser. Conceptos súper relamidos y gastados. Yo no me siento parte de eso. Este año (2004) volver a mostrar una individual (‘Enero, 7:25’) fue súper extraño también”.

–¿Por qué?

“He estado exponiendo mucho afuera. A pesar de que mi trabajo no es localista y en términos formales puede ser entendido en cualquier lugar, aquí se establecen otras relaciones por ciertos códigos nuestros. Para el público más especializado da como lo mismo lo que uno haga. En general –salvo buenas y notables excepciones–, la mirada viene mediada por lo que se espera ver y no por lo que realmente está ahí delante”.

–No hubo lecturas a la altura de la exposición.

“Siento que se le da mucha importancia a esto del espacio privado y a cómo expongo mi intimidad, cuando en estos trabajos a partir de servilletas (realizados desde el 2002) es sólo un aspecto. No se han visto otras obras acá. Pero insistir tanto en la cosa autobiográfica, me cansa un poco. Mi trabajo tiene otro tipo de cruces más interesantes. El espacio cotidiano es una excusa. Obviamente que por ese lado hay una investigación. Pero igual están la transferencia de imágenes, la noción de estructura fotográfica, y los roces con la pintura…”.

–O con el lenguaje digital.

“Absolutamente. Si no tuviera computador, mi trabajo no podría existir”.

Mónica Bengoa (Santiago, 1969)

En la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (1988-1992), Mónica Bengoa escogió la mención Grabado, donde –gracias a la apertura de maestros como Eduardo Vilches y Eugenio Dittborn– comenzó a experimentar con fotografía, desarrollando una producción autobiográfica de disposiciones objetuales. También se especializó en Cine. Entre 1993 y 1998 formó “Jemmy Button, Inc.” junto a los artistas Mario Navarro y Cristián Silva, más el teórico Justo Pastor Mellado. Posteriormente, integró el ciclo de exposiciones “Proyecto de borde”, con Claudia Missana, Paz Carvajal, Alejandra Munizaga y Ximena Zomosa. Entre sus exposiciones individuales destacan “Para hacer en casa” (1992, Instituto Chileno-Norteamericano); “203 fotografías” (1998, Posada del Corregidor); “Tríptico en Santiago” (2000, panel publicitario sobre un edificio); “Sobrevigilancia” (2001, Galería Animal); “De siete a diez” (2003, Galería Oxígeno, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia); “El color del jardín” (2004, Galería Latincollector, Nueva York, Estados Unidos), y “Enero, 7:25” (2004, Galería Gabriela Mistral). Su presencia internacional se ha intensificado en los años 2000, participando en talleres de residencia o en instancias como “Políticas de la Diferencia” (2001–2002, Recife, Brasil-Museo MALBA, Buenos Aires, Argentina); el Festival Internacional de Fotografía de Roma (2002, Mercati di Traiano, Roma, Italia); la Bienal Internacional de Fotografía y Artes Visuales de Lieja (2004, Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain, Lieja, Bélgica), la Feria Internacional de Arte Contemporáneo ARCO (2004, Madrid, España), y “Project of a boundery, portable affairs” (2005, Artspace, Sydney, Australia). Acá fue parte del eslabón emergente que Mellado incorporó en “Chile, 100 Años Artes Visuales” (2000, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes). Ha financiado su producción con Fondart y la Beca de la Fundación Pollock-Krasner. Desde que se tituló, en 1993, ejerce la docencia en la misma PUC. En 2007 participa en la muestra “Poetics of the Handmade” (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Moca, Los Ángeles, EE.UU), en “Daniel López Show” (NY). Y representa a Chile en la 52 Bienal de Venecia (Italia).

Carolina Lara

Periodista, Licenciada en Estética, Maestría en Teoría e Historia del Arte

En Entrevista a Mónica Bengoa en Chile Arte Extremo: Nuevas Tendencias en el Cambio de Siglo. p.73-80. Santiago, Chile. 2008

Chile Extreme Art: New tendencies in the changing century

PHOTOGRAPHIC REALITY SHOW

Mónica Bengoa is tired of being identified with her autobiographical subject. The artist, knowing for turning domestic shots into large photographic series and murals, says she is long past focusing on the depiction of her body and the domestic world to focus in technical transfer process of private images that support colossal staging. Instead of compiling a sort of personal photo album with shots of herself while she is asleep, her kids washing their teeth or the pots in the kitchen –which she continues to do today– what she is presenting is the result of a process, in which the snapshots has been enlarged in he computer, transfigured in chromatic codes, embroidered or painted on hundreds of thistles or paper napkins attached to the wall.

“I’m interested in mixtures, a work that can be an object and a drawing at the same time, both a pictorial and a photographic work, and which can be installed with poise in the wall. I think it’s kind of obsolete trying to classify things into disciplines and justify everything from that point. This is photography. This is painting. The more of a hybrid, the more interested I am” she adds.

What this artist does is called “post photography”. An international trend that landed in Chile in the 90s, and that is found locally in the work of Eugenio Dittborn, in the texts of Ronald Kay, and in the transfer operations from engraving, in which photography becomes both plastic material and thought material.

Bengoa modifies the pictures until she turns “everyday life” into a powerful and paradoxical scene, having as targets the crafts and the technology, the public and the private: or “the real”, displayed on large “screens”. In Tríptico en Santiago (Triptych in Santiago), the concept was taken to one extreme: three shots of her children eating in the kitchen appeared in a huge advertising billboard –one of those rotating billboards– located at Bellavista and Loreto streets. “The contrast between that ultimate disclosure of intimacy provided by that low-profile picture and the structure that was designed to frame generally high-quality and spectacular photographs, gives me the chance to speak of those everyday actions that make up a safe environment but often go unnoticed”.

It is a look at intimacy from a distance. A peculiar reality show based on –she says– Agota Kristof’s life in “The Notebook”, adapted for the stage by the troupe “La troppa” (Gemelos [Twins]). “I’m really interested in that ultimate nonchalance in discussing the most terrible things and also in that austerity in dealing with domestic issues. It has to do with taking an intermediate stance so that I can be personally involved an, at the same time, be open for the audience to participate”.

BODY OF BATTLE

The artist makes it quite clear that she prefers to read fiction rather than philosophy, aesthetics or art theory. So much so that Diamela Eltit’s Lumpérica “was my first approach to the topic of the body as a battle territory”. Back then Mónica Bengoa was a “fan” of Cindy Sherman (New Yorker artist known for her portraits that link the social status of women to horror). Then came along the self-portraits; next, the approaches to the skin, creases, moles, scars, the backs of relatives and friends; later, the works with murals painted with crayons –using only colors corresponding to the ones used in a climate chart. Those were parallel works that represented –to different extents– a territory thing she would cross later in Sobrevigilancia (Overvigilance): the washbasin scene that was recreated using pigmented thistles.

–Why did you stay with engraving in college?

“It was an excuse that represented an interest by a group. mario Navarro, Crisián Silva and others took it together. So did Francisca García and Carlos Navarrete. Basically, I did it because of Vilches. He was one of the precursors in the field, a teacher who gave us the chance to both work with an impressive mixture of media and get to know a much wider conceptual development. So, engraving was never about just engraving and it was always mixed with photography.”

–What similarities did you have as a group? Common subjects?

“We has a certain political stance on everyday developments rather than a clear-cut subject matter. Well, we were classmates from freshman year, we majored in the same area and had the same training. We also shared common interests in literature, cinematography… we understood art as an exercise rather than a finished masterpiece; we saw art as a work in time, an investigation in constant growth and revision that gives rise to new mistakes to improve ‘the hard way’.”

– What do you mean by “the hard way”?

“I mean that every new work should pose challenges, there should be things that are out of our reach, that are new to us, that we do for the first time. By doing this we establish a protocol, an operation system in which we have to be totally aware of the work’s spacial and cultural context.”

Minding the context: Eugenio Dittborn’s influence.

“He formed a very important workshop. It’s not a coincidence that de did that for the first time when I was a student in 1992. After Eugenio made the groups I began working with Mono (Cristián Silva) and Mario. I think he was one of the teachers who raised the most awareness of the specific spot we should install our work. He taught us to bear in mind the exact dimensions of the room, he objects between pillars, etc”.

III. The microscopic gaze

In one of the meetings we had to speak about her retrospective exhibition, when I asked her for details on the distribution of the works in the museum space, Mónica took me to her workshop, where she pointed at a scale model of the museum in which she had displayed small size reproductions of the works in a tentative order. This is, certainly, a common practice for artists who want to imagine how the works will look like positioned specifically and make sure to find the optimal way to arrange them. But in this case the gesture takes on a special charge due to the role scale transformation procedures have in her work. I looked at the scale model for some time, imaginarily circulating through the museum halls reduced to the scale of a toy.

All work of art, Lévi-Strauss proposes in The Savage Mind, is a reduced model of reality (even works of a monumental or natural size, “since graphic or visual transposition always supposes renouncing to determined dimensions of the object”[7]), a miniature destined to grant us an illusion of power over things by means of an object homologous to them, in an operation located in between mythical and scientific thought. There is some of this in Bengoa’s work, which transposes restricted aspects of reality with a rigor that has a lot in common with obsession, due to its extreme meticulousness, but also with games, due to the gratuitousness of the challenge in each work she sets out to make, without any other goal than the pleasure of exploring what happens, and with the certainty that said self imposed difficulty (that which the members of the Oulipo group called constrained writings, limited, faced with impediments) will show us new ways of looking.

Now, it is not trivial that Bengoa’s changes of scale tend toward the production of images in which the object is extremely magnified, such as her images of insects, her enormous greenish sink reproduced with thistles or her felt murals amplifying book pages until turning them into broad geographies in which the spectator feels he or she could get lost in. If maps and scale models normally have in order to control or conquer it, the microscopic gaze, also eager of knowledge, rather tends toward the vertigo of what is endless, to the detail invading all of our visual field and which we feel we could always increase in size, indefinitely, therefore making us feel minuscule, defenseless, vulnerable. The infinite of outer space, as Pascal knew, may be less terrifying than the infinite of what is negligible, of what is minuscule as a miniature universe in which we can get lost in, and which makes our certainty about us being the measure of all thing stagger.

JEMMY BUTTON INCORPORATION

The artist says: “I think my coming into the circuit has been gradual and always with a bit if luck. I’ve never put my energy into trying to become popular in the circuit. I’ve never been like those people who chase curators around and send thousands of résumés or catalogs to a lot of people. But if you happen to do an exhibition abroad, and someone who sees the exhibition gets interested later, she/he may call you. I work hard, I do a lot of exhibitions. That’s why people get to know me.”

–How did you get your first exhibitions?

“My generation was very resourceful. We had been presenting exhibitions in different places since graduation. We opened exhibition spaces. We did an exhibition in that hall in Renca (one of Santiago’s municipalities), at Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna Museum, and at binational institutes. After graduation (1993), ‘Mono’, Mario, Justo and I created “Jemmy Button, Inc.”, which was a key factor to all of us. As usual, people who had done exhibitions abroad were getting more credit. We kind of followed this lead and started to contact people who may have been interested in our work. In 1994 we went to The Netherlands and also received our first FONDART grant.”

–But you got it easier because Justo Pastor Mellado, right?

“I hope he doesn’t get offended, but I think what he did with us is overrated, although it is truth that he was treated as an equal. He took Jemmy Button to Curitiba (1995, XI Engraving Exhibition, Brazil), however, we did the rest. We got that exhibition in The netherlands only because Mono’s brother was living there. In 1996 something similar occurred. We sent our dossier to the Chilean Embassy in London, regardless of the fact that we didn’t know anybody there. ‘Taxonomías’ (Taxonomies) (with artist’s texts: one of the group’s most important works) was a book conceived by us. The bottom line is that Mellado’s job was to write about the project. He never took part in the works.”

ON THE VERGE OF FEMINISM

With artists such as Alejandra Munizaga (at first), Claudia Missana, Paz Carvajal and Ximena Zomosa, Mónica Bengoa has participated in specific projects and managed not to neglect her solo work. “Project of a Boundary” has been another “joint venture” that –at the beginning of the decade of the year 2000– has given her the chance to step over the threshold of new territories into which she would have never ventured on her own. This is how she got to know the New York gallery she was working with, Latin Collector. Bengoa had the chance to participate in the Madrid-based fair ARCO thanks to this gallery.

–Jemmy Button represents some sort of harder conceptualism, and this group of women shows a work filled with other type of sensitivity. Do these joint ventures speak of fluctuations in your work, or you have two clear-cut work areas?

“I feel absolutely comfortable working on exhibition with anyone. However, I had many reservations about taking part in ‘Project of a Boundary’, because I had a problem with the fact that we were all women. I still have that problem. Although we worked very well and we all respect each other tremendously, we have different viewpoints. I don’t feel comfortable with the feminist thinking, because I’m not interested in playing the role of victim or superhero. I need to place myself in the intermediate are of normality.”

–Were any of them feminist?

“Yes. I always find myself giving a moderate opinion, trying to tone down the feminist aspects, because I’m not interested in that. It is a work made by a woman, which shows from miles away. This is not where emphasis should be laid. However, other women from the group were quite conceptual; they work in close proximity to language, conduct powerful investigations and are very rigorous. Maybe I’m in the middle.”

–On an international basis, you have dealt with important curators (such as Korean Yu Yeon Kim). How have you handled criticism in Chile? Have you worked with any other theoretician besides Justo Pastor?

“The truth is that my working with him hasn’t been a positive thing for me. He is a very confrontational figure who isn’t trusted in several areas. Because of my constant traveling, I have managed to keep myself out of this. Now I have started working with someone again (Adriana Valdés in ‘Enero, 7:25’ [January, 7:25]). I would say this is the very first time I work with someone, because, because Justo always had a point of view about the work and wrote without asking much about what I really was trying to express.”

PRIVATE POLITICS

–How have you dealt with the political and cultural changes that have occurred during the post-dictatorship period?

“Politics and public affairs have not been my subject matter. Not because a lack of interest in what has happened. On the contrary, I always try to be tremendously aware of what happens around me. My work deals with other kind of policies, private ones, so to speak. I think the need of extending the boundaries of photography depends on one’s presence and on a certain notion of truth that the language is able to render.”

–How much influence has had the development of the cultural institutionalism on you?

“Honestly, I think these last years I have kept myself out of this, mainly due to my trips, but also out of boredom. I feel that some people (in the art world) continue to drag things from the past, things that don’t make any sense whatsoever today, overused and clichéd concepts. I don’t feel part of that. Besides, presenting a solo exhibition this year –‘Enero, 7:25’ (January, 7:25)– has felt very strange.”

–Why?

“I have been doing a lot of exhibitions abroad. Although my work is not local and can be understood in formal terms anywhere, there are other kinds of relationships here because of our own codes. The more specialized audience doesn’t care about what you do. Usually –unless some good exceptions– the view is regulated by what the audience expects to see rather the the kind of reality that is there.”

The interpretations failed to raise to the occasion.

“I think people give too much importance to the private space thing and to the way I disclose my intimacy, because these works made from napkins (from 2002) are just one side of me. The audience here hasn’t seen other works. My work has other most interesting kind of mixtures. I get a bit tired of people insisting so much on the autobiographical subject. The everyday space is an excuse. Obviously that area needs investigation, but the transfer of images, the concept of photographic structure and the friction with the painting…”

–Or with the digital language

“Absolutely. If I didn’t have a computer my work couldn’t exist”.

Mónica Bengoa (Santiago, 1969)

Mónica Bengoa studied at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (1988-1992). She majored in Engraving. Communicative teachers such as Eduardo Vilches and Eugenio Dittborn encouraged her to experiment with photography. Soon she was drawn to an autobiographical production of objectual arrangements. She also majored in filmmaking. From 1993 to 1998, Bengoa was involved in the group “Jemmy Button, Inc.” Subsequently, she took part in a series of exhibitions called “Project of a Boundary”, along with several artists women of her generation. Some of the solo exhibitions are: “Para hacer en casa” (To do at home) (1992, Chilean-North American Cultural Institute); “203 fotografías” (203 photographs) (1998, Posada del Corregidor); “Tríptico en Santiago” (Triptych in Santiago) (2000, an advertising billboard on a building); “Sobrevigilancia” (Overvigilance) (2001, Galería Animal); “De siete a diez” (From seven to ten) (2003, Galería Oxígeno, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia); “El color del jardín” (The color of the garden) (2004, Latincollector Gallery, New York, United States), and “Enero, 7:25” (January, 7.25) (2004, Galería Gabriela Mistral). Her international presence was widened from the year 2000, due to her participation in in-house workshops and projects such as “Políticas de la Diferencia” (Policies of the Difference) (2001, Recife, Brazil–2002, MALBA Museum, Buenos Aires, Argentina), as well as international events including the International Photography Festival of Rome (2003, Mercati di Traiano, Rome, Italy); the International Photography and Visual Arts Biennial of Liège (2004, Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain, Belgium), ARCO Art Fair (2004, Madrid, Spain) and Project of a boundary, portable affairs” (2005, Artspace, Sydney, Australia). Back in Chile, she was part of the emerging group of artists that Mellado put together for the retrospective “Chile: 100 Years of Visual Arts” (2000, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Santiago). Bengoa has financed her projects through FONDART and the Polock-Krasner Grant. Since her graduation in 1993 she has been working as a teacher in her Alma Mater. In 2007 she takes part in the exhibition “Poetics of the Handmade” (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, USA), in “Daniel López Show” (NY) and represents Chile in the 52 Biennale di Venezia (Italy).

In Interview to Mónica Bengoa in Chile Extreme Art: New tendencies in the changing century. p.275-278. Santiago, Chile. 2008